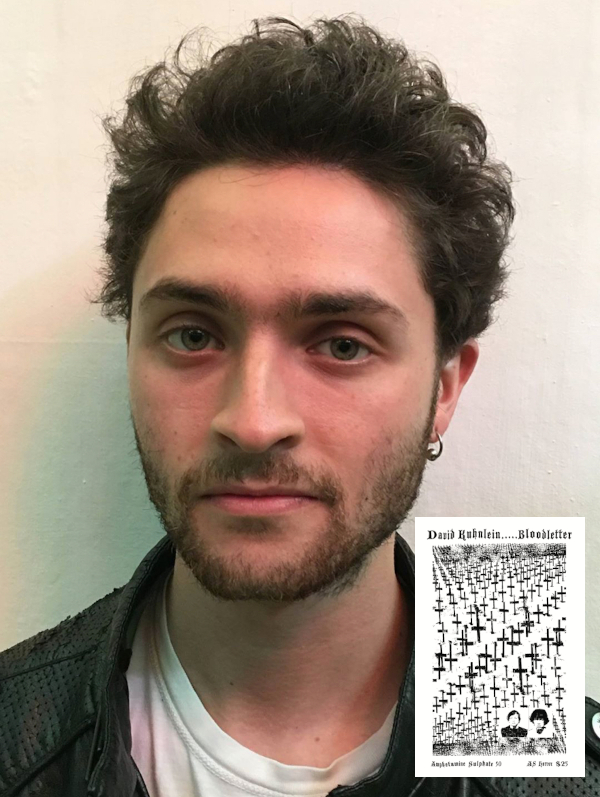

Writer, poet, editor, visual artist, and actor: David Kuhnlein’s work is expansive and mutant. Working with fellow alchemist Sean Kilpatrick, Kuhnlein has developed a concentrated form of text: concise, insidious, visceral. Blood boiled into tar. His haunting first novel, Die Closer to Me, a work of science fiction set on the planet Süskind, was released last year on Merigold Independent. His novella Bloodletter was recently released with Amphetamine Sulphate, exploring serial killers Béla Kiss and Adolfo Constanzo. Kuhnlein has previously released a book of horror film reviews Six Six Six and a poetry collection Decay Never Came featuring his collage work. Along with tragickal, Kuhnlein co-edited a recent horror anthology Lizard Brain. Kuhnlein has also acted in many of Kilpatrick’s films, appearing as figures ranging from Antonin Artaud to Kurt Cobain. His resemblance to Vincent Gallo in one is uncanny. I sat down for a Zoom conversation with the shapeshifter before sending over some questions.

Matthew Kinlin: In Blood and Guts in High School, Kathy Acker writes: “Dear dreams, you are the only thing that matter.” What do you dream about?

David Kuhnlein: Last night I dreamt I died. The room I fell asleep in was on fire and bent into an L-shape, the bed was at one end while a furnace cackled explosively around the corner. Faces flickered quickly enough in the smoke for me to question their “realness.” (But also, I knew that I was dreaming, and I was impressed with the detail of my imagination/unconscious—every face was so crisp, so unique, but there was a cap on my lucidity: it did not allow me to stop myself from suffocating to death.) As the smoke billowed I felt compelled to crawl towards the furnace. I watched myself crawl, open the grate and wiggle my way face first into the flames. It was very painful, my arms becoming embers and then ash, but then the heat, the pain, and my cough receded and I was able to explore the space more freely. I dream a lot about death, but unlike the movies I don’t wake up when I die, the dream continues.

MK: Anne Sexton’s poem Her Kind, opens with the lines: “I have gone out, a possessed witch, haunting the black air, braver at night; dreaming evil.” Is there a connection between dreams and evil?

DK: Evil is, surprisingly enough considering the horrifying books and movies I most enjoy, not something I spend much time thinking about. I remember this line from Sartre’s Saint Genet: “Evil is a projection,” which was such a simple and troubling idea for me when I first read it in my early twenties, because it suggested the possibility that the evil that I thought existed out in the world existed equally in myself—that I am not separate from the worst of us.

I’ve always been an active dreamer. Writing them down is a very useful method of exploring the darker, less (socially) acceptable sides of my personality, what Jung would call “the shadow.” My sadness, anxiety, rage. These are more easily explored in the dreamworld and in writing—where there are fewer consequences than in waking life.

MK: The figure of the witch takes me to the work of your grandmother Barbara Mahase Rodman, or Babbie, and her interest in the occult, whose writings you edited and published, including her gothic romance novel Olas Grandes. The grandmother can be a powerful compass for the imagination, from Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales to David Lynch’s early short The Grandmother. Can I ask how this editorial process was for you and any small details that Babbie shared with you about Trinidadian myths and magic?

DK: The editing of Babbie’s work is ongoing—I’m working very slowly on my next favorite manuscript of hers (after Olas Grandes). It’s called Dreaming of Castles in Spain.

Throughout most of my interactions with Babbie, her interest in the occult was understated. It wasn’t until I started reading her writing and sorting through her collection of books that I discovered this shared interest. Around the time of this discovery, she was diagnosed with dementia. There were moments of lucidity, however, and during our last serious conversation, which in retrospect makes no sense in terms of its duration and quality, we discussed Aleister Crowley, Carl Sagan, and other shared important figures. She said, “The human will is the strongest force that we have access to.” I had never heard her say that before. It was a powerful moment.

I think it follows that dreams and waking life feed into each other, are two sides of the same coin, but travelling further into Hindu mythology, there are not two but four states of being: waking life, dreams, dreamless sleep, and turiya—the immortal, non-bodied self. Turiya is obviously the most elusive of these four states, some of us may never experience it in our lifetime, so I thought it appropriate that in Die Closer to Me, a drug would be synthesized that granted the user easy access to this mysterious state of being.

MK: According to Bataille, a kiss is the beginning of cannibalism. Reading like pica, or the condition of eating things other than food, can inform how one writes. There are a lot of literary references stitched throughout your work, such as the planet in Die Closer to Me named after German author Patrick Süskind. As a cannibal, which texts have you studied and ingested?

DK: I took the idea of naming my planet after a writer from Sam Delany’s Babel-17, in which the protagonist’s spaceship is called Rimbaud. Yes, my work holds lots of conscious references to films and books. It’s also fun for me to find links between my work and texts that I hadn’t yet read at the time. For example, I read Brian Evenson’s novel Last Days after I wrote the sections in Die Closer to Me about devotional hand amputation. It was as if the subject matter had crawled off the shelf and scuttled into my ear in my sleep. [insert GIF of Thing from Addams Family]

Here I’ll include things that I’ve read twice or more in the past couple years: Reinaldo Arenas’ Before Night Falls; Sontag’s Against Interpretation; Crowley’s Book 4; Plato’s Apology; Kevin Killian’s 2017 PowerPoint presentation/talk he gave in Berkeley, which included an essay he wrote on Forrest Bess called “The Future of the Body,” Jack Spicer’s poem “Goodnight (I Want to Kill Myself),” and ended with a nude photograph of me balancing on a ladder; Sean Kilpatrick’s Shock Test; Virgilio Piñera’s Selected Essays …

MK: In my mid-twenties, I came across a copy of Cold Tales by Virgilio Piñera, the notorious and openly gay author who was exiled in Buenos Aires before returning to Cuba in 1958. Famously, Che Guevara threw one of his books across the room during an interview in Algeria, shouting, “How dare you have a book by this foul maricón?” Can you discuss Piñera and your translations of his essays?

DK: Piñera’s fiction (Cold Tales and Rene’s Flesh) has been translated but his essays and many of his plays have not. My translations, so far, include a couple of my favorite essays of his. “Kafka’s Secret” is a hilarious and chastising discussion on why writing is an art and not a science. The other is a devotional essay called “Eristics of Valéry.”

I got in touch with his estate to see if they’d allow me to publish them. If I don’t get permission, that’s okay, although I hope other people in the English-speaking world get a chance to read them.

MK: The first publication I read of yours was Six Six Six, a collection of horror film reviews, which explores some modern classics such as Hereditary and The VVitch. The former film makes repeated reference to Paimon, a demon whose powers include: “knowledge of past and future events, clearing up doubts, making spirits appear, creating visions, acquiring and dismissing servant spirits, reanimating the dead for several years, flight, remaining underwater indefinitely.” What is your relationship with horror films and grimoires such as The Lesser Key of Solomon?

DK: My relationship to horror films is complicated—I love the genre, but I didn’t really start to watch them until I was in my twenties, so even though I’ve seen a lot of them, I’m still playing catch up. It takes a lot to scare or disgust me. Everything I reviewed in Six Six Six I recommend for one reason or another. There are many reasons to watch a film beyond it being enjoyable.

My relationship to grimoires: Well, I’ve read The Lesser– and The Greater Key of Solomon. I’m interested in ceremonial magick the way I’m interested in religion: I enjoy learning about its history, comparing and contrasting it with other occult practices, though I haven’t practiced ceremonial magick at the crib in a while (like anything, it takes time and energy, which I often funnel into my writing practice). Crowley’s Book 4 is divided into two sections, the first deals with yogic meditation techniques, the second with the symbolism in ceremonial magick. Honestly, I’m more drawn to the mysticism in the first half of the book opposed to the magick of the latter half—there’s enough there for a lifetime.

MK: Your science fiction novel Die Closer to Me was released last year, set on the planet Süskind, a failed disability experiment of Earth. Having these vaguely related characters navigate this broken world gave you a lot of space to play with and explore. For such a dismal place, it’s a lot of fun to read. What was the inception of the novel? I’m currently reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home, which is a beautiful work and one you’ve mentioned as a touchstone.

DK: First, a short story about my time working on a farm: After a two-year period of being a vegetarian (my body couldn’t handle it), I returned to my omnivorous nature. I missed the sense of power and domination that I got from chewing meat (believe it or not). Me and my co-workers each bought a live chicken from a guy called Solomon the Chicken Man. Two of us were experienced in the slaughtering, scalding, plucking, gutting method we would soon perform, and two of us were not. I was not, nor was my friend Mary. (Now that I think about it, Mary is the one who introduced me to Always Coming Home—thanks, Mary!) The day before we cut the chickens’ throats with razor blades and bled them out in our arms, Mary turned to me while we were harvesting spinach and said, “If I were the chicken, I’d want you to be the one to kill me.” Two hours after I slaughtered my chicken, it was spatchcocked with a little salt, pepper, and olive oil. It’s no exaggeration to say that this was, by far, the tastiest chicken I’ve ever eaten. Anyone who’s read my work will see how deeply these particular memories are impressed on me.

In addition to this, I live in Oakland County, which is where Dr. Jack Kevorkian—my favorite local celebrity—euthanized over 130 patients in his Death Van or Suicide Machine. I drive past the cemetery where he’s buried on the way to the hardware store. Maybe he’s communicating with me. The cops are still called to routine deaths in our area because of the fear that he instilled in the local populace. He was known as Dr. Death but wanted to be called Dr. Life, haha. We’re not ready for that. With my sci-fi book, I wanted to show that, sometimes, killing is caring. Or, at the very least, evidenced by the story above, it’s a complicated thing.

Die Closer to Me was also informed by my reading of Derek Humphrey’s Final Exit, a practical book on how to kill yourself. It has sold millions of copies. There’s one particular chapter in the book that lists all the things needed to effectively end your life without botching it (a very common phenomenon). There are lots of tips to avoid common pitfalls. I can get behind anything where a pitfall means to continue living.

MK: I find your writing takes surprising turns, in terms of the structure of each sentence. It’s often raw and visceral. I know you work closely with Sean Kilpatrick, and more recently Danielle Chelosky for Bloodletter. I came to Kilpatrick when I first started writing. I found his Sucker June particularly depraved and fascinating. Can you talk about the partnership of working with him and how discussions with him about Hungarian serial killer Béla Kiss led to Bloodletter?

DK: I’ve had my work edited (not just touch-ups) by a few people in recent years. I’ve learned a lot from each of them. Kilpatrick’s edits remind me of Diane Williams’ edits (she edited a story of mine that was in her literary annual NOON in 2023). They both cut, rearrange, and sometimes rephrase. The cut or remix of a piece is an uncanny way to see whatever it is you’ve written through new eyes.

In March of 2020, paid to stay home, I was writing like a madman and found a compatriot in Kilpatrick’s keyboard. He had edited a few short pieces of mine when he suggested Béla Kiss as a potential subject (he’d write something himself, he said, but figured I knew more about the occult aspect of Kiss’ crimes) and offered his editorial services. I was looking for a stage upon which to cast my attention so this suggestion arrived at the perfect time. From March until June we sent drafts back and forth and at the end of those three months we had a novella (and the second half of Bloodletter). It was the longest piece of fiction I’d written and I learned a lot writing it. (I think the last line of the book has a lot to do with my experience slaughtering the chicken.)

By the time Chelosky saw the manuscript it had gone through so many drafts that it felt cemented in my mind. She brought a fresh pair of eyes to Bloodletter, helping me see where it still needed work. Her edits were fantastic, especially the work that we did on the first sentence (arguably the most important sentence) of the book. She was also a huge advocate in getting the book published. When I look at that book in the flesh I feel like bowing to everyone involved. It turned out so beautifully.

MK: Returning to cannibalism, I recently watched Perdita Durango with Rosie Perez and Javier Bardem as a couple of border-hopping killers that kidnap a pair of teenage gringos for ritualistic sacrifice. The film and Barry Gifford source novel 59 Degrees and Raining: The Story of Perdita Durango take elements from the case of Los Narcosatánicos. Can you explain what drew you to writing about the Narcosatanists?

DK: I simply wasn’t done writing first person occultist serial killer fan fiction. I found out about Adolfo Constanzo from reading articles about the crossover between serial murder and occultism. His cult interested me for several reasons. I spent a couple of impressionable years in the early nineties living in Laredo, Texas. My dad worked across the border in Nuevo Laredo. A lot of my favorite childhood toys were from Mexico (I still have my maracas). I thought that I might be able to use memories and images from my childhood to catalyze a short book on Los Narcosatánicos. I remember hearing stories and seeing photos in the paper of men hanging beneath highway overpasses. The book poured out of this impression.

MK: The public’s consumption of serial killers is a strange phenomenon, such as the recent television series Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story made by Ryan Murphy, who also created the high school musical Glee. I remember reading Helter Skelter: The True Story of The Manson Murders as a teenager and how that type of writing lends itself to a certain obsessiveness over trivia, such as death to pigs written in blood. How do you understand the push-pull relationship between people’s attraction and repulsion of serial killers?

DK: I remember the first time I met someone who was “obsessed” (her word) with serial killers and how strange I thought it was at the time. I’m interested in things I don’t understand. Reading about all of the (usually) women writing to imprisoned killers really piqued my curiosity. I think part of the fascination society has with killers is that they have inflicted their darkest, most disturbed fantasies on the waking world, whereas the majority of us release those impulses in other ways: making art or dreaming for example.

I have a strong stomach, and didn’t mind doing research on Constanzo and Kiss. They are both very interesting figures, and not a lot has been written about them, so I was happy to add to the pile.

MK: In an interview for BRUISER with Jesse Hilson, you mentioned Susan Sontag, who wrote fiction, nonfiction, films, and essays about varied figures such as Artaud and Taylor Mead. Your work seems to operate at junctions between different impulses: genre fiction, nonfiction, poetry, film criticism, your Torment column, visual work in Decay Never Came featuring collage work inspired by medieval paintings, acting in Sean Kilpatrick’s films, and the performance aspect of your live reading night Cafe 1923 that you host in Hamtramck, Michigan. Can you speak about how these different aspects relate?

DK: It’s all an experiment, this stuff. The acting, reading, writing, art. Some of it works, some doesn’t. I work best by having several projects going at once. I bat ideas around in my head on the daily adventures I take with my dogs. Seeing what has lasting power and why. One reason why I work across multiple modes is due to inspiration or a lack of it. I really need a heavy dose of inspiration to write fiction, which fluctuates like my moods. I don’t mind writing reviews when I’m not inspired, because I can always come back later to fix them. Returning later to fix poetry or fiction I wrote out of habit (without inspiration) almost always ends up in the trash. I try to keep the writing muscle flexed in some way, regardless of whether or not I’m moved. Sometimes I feel moved to do something visual. I find cutting things out of books and newspapers very satisfying, so I collage.

MK: This brings me to your recent horror anthology Lizard Brain that you co-edited with tragickal, where you invited twenty authors to contribute. Can you discuss this project?

DK: tragickal and I were in talks about releasing a book of mine when they had the idea to do a horror anthology. I agreed to help solicit and edit the work. We told the contributors only that we were soliciting horror fiction, nothing in regard to theme, so the pieces that lean really heavy into the reptilian theme are pure synchronicities. The organization of the pieces into body systems—musculoskeletal, endocrine, reproductive, prosthetic, and nervous—is due to my interest in medicine as well as making mix CDs for my friends. I love the way a mix can tell a pieced-together story, the whole greater than the sum of its parts. We plugged the stories into bodily categories after they’d been sculpted, like Frankenstein’s monster.

MK: I am aware you have another book coming out with tragickal called Ezra’s Head, which is a novella and some short stories, similar in structure to a book like Brian Evenson’s Altmann’s Tongue, all set in Michigan. How would you describe this work and its relationship to Michigan? I have never visited but my mind wanders to the haunted borderlands of It Follows and the noise scene that emerged there: Wolf Eyes, Hanson Records, etc.

DK: Most of my life has been spent in Michigan. I love it here. We’ve got everything—fresh water, sandy beaches, luscious forests, abandoned shipping facilities, beautiful mansions, cockroach infested housing projects, manicured lawns, gritty clubs tucked beneath elegant ballrooms, rabid skunks, territorial deer, sand dunes formed by ancient glaciers—pretty much like everywhere else. The titular “Ezra’s Head” novella within the Ezra’s Head project feels like the spiritual successor to Die Closer to Me, in that the sci-fi and suicide themes are similar, but it departs with its interest in satanism and the modernist writers. Figures such as Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf, and Edith Sitwell serve as a kind of collective antagonist. I found a companion in William H. Gass’ In the Heart of the Heart of the Country. The projects feel similar. Stories that revolve around a sense of place, like a demented love letter to the soil you’re built from.

It Follows is a pretty good portrait of the suburbs of Detroit, the atmosphere is amazing. Other films I’ve seen recently that paint accurate portraits of the area are Dinner in America and The Rosary Murders. Funny you mention Wolf Eyes, I’ve seen those guys play a lot. There used to be a psych-jazz night at a local bar that always had really various and bizarre acts. The most impressive and memorable show I’ve been to here was a noise show on Halloween, at a house that was called something like Electric Piss Waterfall House. All thirteen noise groups began playing at the same time in different rooms in the house, and the audience toured the house like a haunted museum, listening from room to room for the duration of a couple of hours.

MK: Finally, in the BRUISER interview, you also mentioned “birds in hell”. This reminded me of Max Beckmann’s 1938 painting Bird’s Hell, made after Beckmann fled Nazi Germany. It shows a monstrous scene of brightly colored birds torturing and cutting open humans. How do you imagine hell?

DK: Off the top of my head, I imagine hell somewhere between being an incredible literary concept, and a place that exists within us, a place where we forget who and what we are, a place which no amount of flames or claws can destroy, revealing us to ourselves. A devastatingly sad place. A place of our own that we made.

Matthew Kinlin lives and writes in Glasgow. His published works include Teenage Hallucination (Orbis Tertius Press, 2021); Curse Red, Curse Blue, Curse Green (Sweat Drenched Press, 2021); The Glass Abattoir (D.F.L. Lit, 2023); and Songs of Xanthina (Broken Sleep Books, 2023). Instagram: @obscene_mirror.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.