When my longtime yoga teacher, Genny Kapuler, read what I had written about her, she said, “I feel honored to be one of the beads in your mala, one of your sisters.” I like to think of this book like that, as a poetic prose meditation on my friendships with girls and women. I started the project in 1990s, writing some notes about childhood friends, and then I put it aside. This is a book that couldn’t be written until later in life. A few years ago, I went back to the project, expanding it to include mentors, authors, and characters.

Marlene

We didn’t confide in each other. We weren’t that close. We’d cruise the drive-ins in your red Mustang and go to parties together, searching for the boys we’d hook up with next. At a Christmas party in ’66, I met a guy who I ran away with a few months later. Broke my father’s heart, although back then, I wasn’t quite sure he had one. After we children were gone and grown, he and my stepmother moved into a new house and bought a boat. One day you came along to watch him pull me over Lake St. Clair on water skis. I was treading water and holding my hand up to say stop, but he kept plowing forward—perhaps distracted by your curvy body in a bathing suit. He might have run me over, except in the nick of time, you tapped him on the shoulder. I still remember the look on your face when he cut the engine and swerved the boat around me.

Donna

I’ve tried to find you now and again, but with no luck. Your name changes with this marriage and that marriage and you keep moving further and further into the suburbs until finally you disappear. We were roommates for a while in an apartment on Manistique Street on the Eastside of Detroit. When you and your baby came home from the hospital, I was sleeping on the couch. Across the alley in my old apartment, my ex-boyfriend was sleeping with another girlfriend. You dressed up in a negligee and I took photos to send to your husband in Vietnam. Late into the night, we talked about your Jim and my new boyfriend just home from the Marines. Forget the one in back, you said, get married and have a baby with the guy outside in his car waiting for you. I used to take care of your baby, but now I only remember a photograph with cereal on his face.

Linda

I was working as a secretary in a data processing department at Chatham Supermarkets. You were working for a travel agency in Southfield. We were roommates in a flat in Madison Heights. You were reading about hypnosis. One day you asked me to sit on a stool while you tried to hypnotize me, swinging back and forth a rose birthstone on a chain. Your boyfriend was there, too. I was on the verge of tears. We went to a club with fake ID, and I had a panic attack. I never could handle alcohol. I crouched down on the floor in the back of the car. I remember telling you that your boyfriend couldn’t be there all the time. There was only one bedroom. We must have lived together for a couple of months before you left with him, and I moved back into the city for a new job. When I look for you now on Facebook, low and behold, you are a psychologist.

Lucy

You were tall, slim, and Black. We used to go out to lunch together. You worked in accounting at Faygo Pop and I was the secretary for the sales manager. You lived at home with your family, and I was sharing a flat with a roommate on Outer Drive. We both rode the bus to work. After I inherited my grandfather’s old Dodge, sometimes I’d drop you off at home. I remember how you would slide down low in the seat so no one could see you as we drove through the neighborhoods. Sometimes instead of eating lunch, we’d go to Hudson’s Department Store. Sometimes you show up in my dreams when I’m back in that office. We once imagined going on a trip together, maybe down south where you had relatives, but this was ’69 not long after Martin Luther King was assassinated, and we were afraid to drive out of the city in the same car together, but I remember we imagined it and then decided not to.

Faye

You were seated on a stool and students were sprawled around the room, some at desks, some on the floor. You were silent for a few minutes. You had us write about a stone that you had placed on a table. Some of the students read what they had written. I was too shy to read out loud back then, and I was relieved you didn’t call on me. The semester assignment, you said, was to choose an object we could carry around and write several poems about it. After class, I went directly to my counselor and dropped the class. Then I went to the bookstore to buy some of the books on your syllabus, including Soap by Francis Ponge and your book—A Man Is a Hook. Trouble—poems with fictional truth telling narrators and your surreal pointillism drawings, e.g, a man’s headless body with penises erupting from every orifice. My friend Sally took classes with you, too. She loved your experiments. You were one of the best teachers ever, she said. I hadn’t thought about that first workshop in years. Then the other day ago, in an on-line class, a student in Hawaii was talking about a teacher from whom he’d learned a lot about poetry, and it was you. You moved to Hawaii in 1980 and you’re still there. For a while after your workshop, I carried an object, a bobby pin around with me and took notes in my journal. My mother used to snap pin curls into my hair with bobby pins. During World War II, a Detroit man road the buses, collecting unhinged hair pins and donating them for the war effort. A little thing can become a big thing. Even if we aren’t aware of it.

Bernadette

We once took a trip together to New York in my old Honda, the radio on the blink, but we had a tape recorder with us, and we shared earplugs, one for you and one for me. On the way home, as we passed through the Pennsylvania mountains and over the Ohio fields, on some backroad we saw a man with felt paintings for sale, several propped up against his car. I made some comment and then we argued—you said a felt painting could never be art. It got hot and close in the car with no way out. A slap on the knee. Was it you or me? I don’t remember. And neither do you. Later you hooked up with Al’s best friend Joe, and you two married, moved up north, then a breakup, then reunited, but Joe died from a heart attack just days before he planned to come back home. A few months earlier, he was in New York, and he phoned me. He wanted to meet and talk. But I was helping you, and you were so unhappy that I didn’t want to get in the middle. So I declined. I was kind to him, I think, but I didn’t expect him to die. I had known him for years, and loved him. I flew to Detroit and helped you pack up his painting studio. Some years ago, on my way up north to visit with my sister, I stopped in Traverse City and we had dinner. You were retired from the library and involved with a theater group. Even though years have passed since I last saw you, this morning, I woke up thinking about you and that silly argument.

Nancy

I used to bring my four-year-old daughter to class with me. She’d sit quietly beside me and draw while you lectured and led discussions about 19th century novels. When I stopped by your office to talk about the paper I was writing, you gave me your home phone number just in case I had any questions. I was writing on Jane Eyre and Hard Times. I remember working in the typing room in the library and every so often going downstairs to the phone booth to call you. You gave me your home phone number. I’d read a few sentences, and you’d comment or ask another question, then back to the typewriter. In a very supportive letter, recommending me for grad school, you mention my paper was about marriage, about power, inheritance rights, the laboring class, and the educational system, surely many of the points you had lectured on. At the time, I was absorbed with my own marriage and family problems; with two children and not much cash, I needed to figure out how to separate from my children’s father. No wonder I was writing about marriage. I remember once speaking to you about my concern that pursuing a graduate degree was a selfish endeavor, not useful to society. You reminded me that my happiness was beneficial to society. You must have also talked about teaching and the history of ideas. A few years after our class, you published a book, with much acclaim, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. Maybe I never would have applied to Wayne State’s grad school in English if you had not encouraged me. And in that case, I might never have become a teacher for the many students who I later encouraged. Lines of energy would have reformed and rearranged in a completely different pattern.

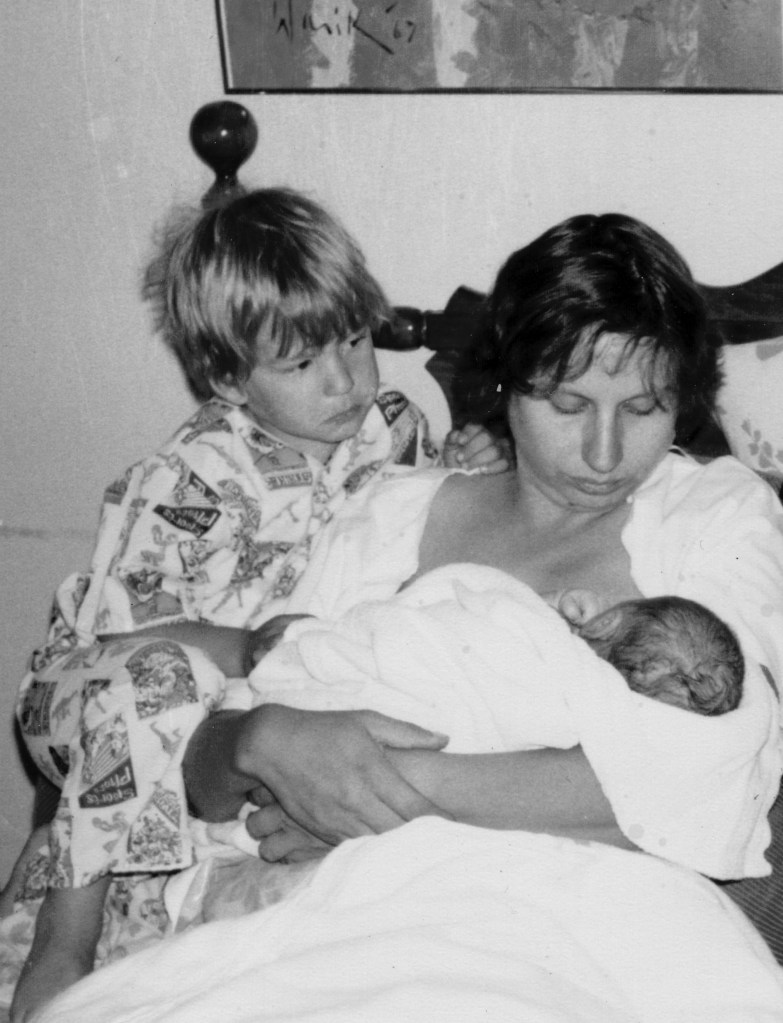

Kathy

Late at night, I find you sitting on the edge of the sofa in the dark listening to Van Morrison. You are usually a quiet person, kind of reserved, sometimes a little anxious, maybe more so this year after Jim’s unexpected death. When I first met you, you were in med school, and you lived in a communal house two doors away from us. We had a dinner coop on our block. Students, artists, writers, social activists. We were going to change things, live differently. When I became pregnant, you said you’d help with the birth. My other labor had lasted two days, and this baby was a month late. Gravity can help, I was told, so I kept pacing and singing about the saints marching in. While Allen helped me concentrate on my breathing, you caught the baby and helped the placenta release. Then you had to go back to school. Word was out that a med student was helping someone with a home delivery, and that wasn’t allowed back then. Today, I am upstairs in your house preparing for a reading and you’re downstairs in your office, humming and singing in preparation for tomorrow’s choir practice. Out front the trees are swaying in the wind. In the back, a flock of blue jays mingles with the squirrels for the seeds you scatter. I remember just eight months ago, walking along with you, Jim and the geese on the lawns at the Ford mansion, now a museum and public park. Jim was quiet and gentle. I didn’t know him in the ’70s.

Norma

You were intellectual, a history buff. You didn’t like to gossip. You always wore jeans and a tee shirt. Your face would often break into an easy wide laugh, especially around children. When our toddlers became friends at nursery school, we used to take turns with playdates and babysitting. We were part of a group of mothers who hung out together with our children. There were picnics and roller-skating parties. Many afternoons, we sat in my kitchen drinking coffee and watching our children play in the sandbox. You were working at Wayne State bookstore. I was in grad school. You had your second baby in a birthing center, and I came along to help take care of Jamie. After the children were a little older, you took a job delivering mail on the southwest side where you had grown up. Your father worked for the post office, and how easy it was for you to stop at a bar on breaks, you said, lunch hours and after work. Then more and more. Not long after, you and your husband divorced, and Al and I split up. For a while you were staying in a hotel on Cass Avenue. Some years back when you visited me in New York, we had dinner together at an Italian place in the East Village. Then my emails were returned and phone numbers disconnected. After paying for a people search, voila, we are reconnected and there you are on FB surrounded by—I count six—grandchildren.

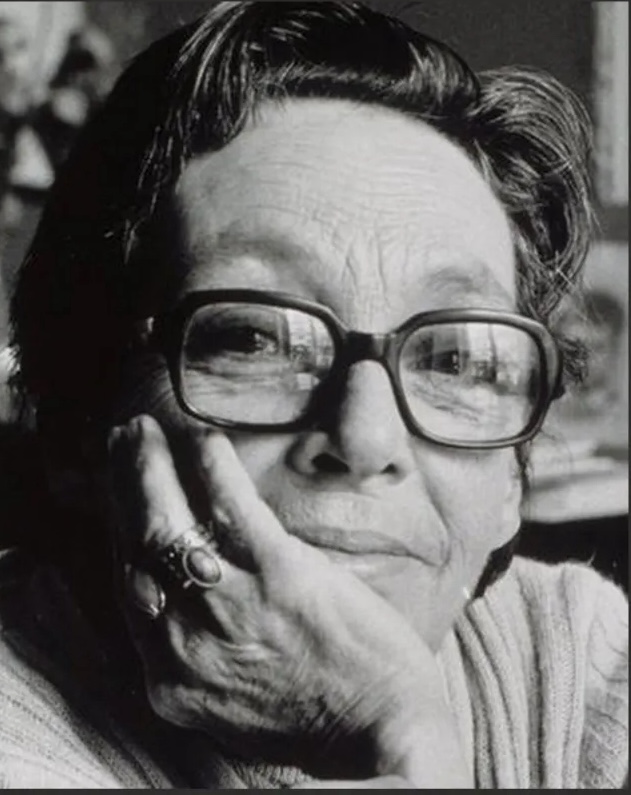

Grace

In the first day of an undergrad class on 20th Century American Lit, the male teacher handed us the syllabus. There were too many books,” he said, and he suggested cutting, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute. I looked around and raised my hand. “But there are only two women on the syllabus. Can’t we eliminate one of the men?” I don’t remember which book he dropped, but it wasn’t yours. Not long after, you came to the Detroit Institute of Arts to give a reading. You were about sixty years old, wearing jeans, chewing gum and popping bubbles. When someone asked why you didn’t write more, you just smiled and said, “Art is long, but life is too short.” Your character Faith and her friends were social activists (like you). My generation was the age of your children, and we were also reinventing family to include friends, live-in lovers, sometimes with communal living. You write in the introduction to your collected, “As a grown woman, I had no choice. Everyday life, kitchen life, children life had been handed to me, my portion, the beginning of big luck, though I didn’t know it.” Into your stories, you channeled the voices of friends and neighbors in your kitchens, on the stoops and in the playgrounds. Nothing flat or monologic, no static voice, very open ended, the world and consciousness alive and continually changing. In one of your early stories, Faith’s little boy, Tonto, talks her into holding his feet while he yells something so important out the window of their third floor apartment to his older brother—he yells, “Richie, hey, Richie! . . . I’m playing with your new birthday-present army fort and all them men.” He slams the window shut and says, “I bet he’s mad!” I remember leaning out a window in our Brooklyn apartment as my son and his friend raced down the street after tearing a hole in a wall I had just repaired, and I yelled, “I hate boys!” Did I really hate them? Not hardly. Maybe a little too permissive, but like Faith and perhaps you, too, I was his lawyer.

Marguerite

As we walked along Canal Street, my poet-lover carried The Lover in the pocket of his long black coat. You’ll like this book, he said. It wasn’t a gift. It must be returned. On the cover, a stain where he’d once set a coffee cup over your eye. After returning the book, I bought my own copy and made an identical coffee stain over your eye. A disturbing and seductive coming of age story. Autobiography and fiction intertwined. Your story, but not your story. A child on her way to school in a silk dress, high heels and a man’s floppy hat. A fifteen-year-old girl with an abusive brother, a mentally challenged younger brother and an unstable sometimes violent mother. And all three of you “loved her beyond love.” To write straight out narrative would have captured the desire and clipped it short. I learned a lot about writing novels from studying your books—the indirectness, the shifting of time and point of view, the circling around images and looping back with memories of the scene at the ferry—the face, your face, the hat, your hat, the river, the debris, the muddy light. Each page a poem. Upon observing the mother mentally drifting away from her, you and your narrator explain: “I went mad in full possession of my senses. Just long enough to cry out. I did cry out. A faint cry, a call for help, to crack the ice in which the whole scene was fatally freezing. My mother turned her head.” The ship heads away from the shore, the lover’s black car disappearing as you travel across the China Sea, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, the Suez Canal, landing in France where you live the rest of your life.

Mary

When you left your neighborhood for the first time, as a child, you were surprised to discover that not everyone spoke with an Irish brogue. Both your parents had immigrated to New York from Ireland. After attending an all-girl Catholic high school, you became a Dominican nun, for fifteen years living in a convent and teaching Greek and Latin in Catholic schools in East New York. Your first lover was a young man who left the priesthood for political reasons. You left because the Church wasn’t serving those who needed the most help. You were active in Vietnam anti-War protests and in the Civil Rights Movement. As a professor at Brooklyn College, you helped young women—with little or no experience outside their families and neighborhoods—learn how to teach in Brownsville, one of the poorest neighborhoods in NYC. You were the core faculty on my Ph.D. committee at Union Graduate School, and you talked to me almost every night when during a tenure review at LIU, I was attacked for having attended a non-traditional program. I remember visiting with you in the Catskills, the walks we took in the forest. Your life with your husband was calm and quiet, not like my up and down bohemian family life in Brooklyn. Even though we were a generation apart and lived utterly different lives, we liked to visit museums, see films, and talk about books. You’re ninety years old now and still living in the Catskills. Your husband died, but you have friends and a young man takes you to the supermarket twice a week. You talk excitedly about a film you saw recently, The Quiet Girl, Claire Keegan’s story about a neglected Irish girl. You remind me that you had a very happy childhood.

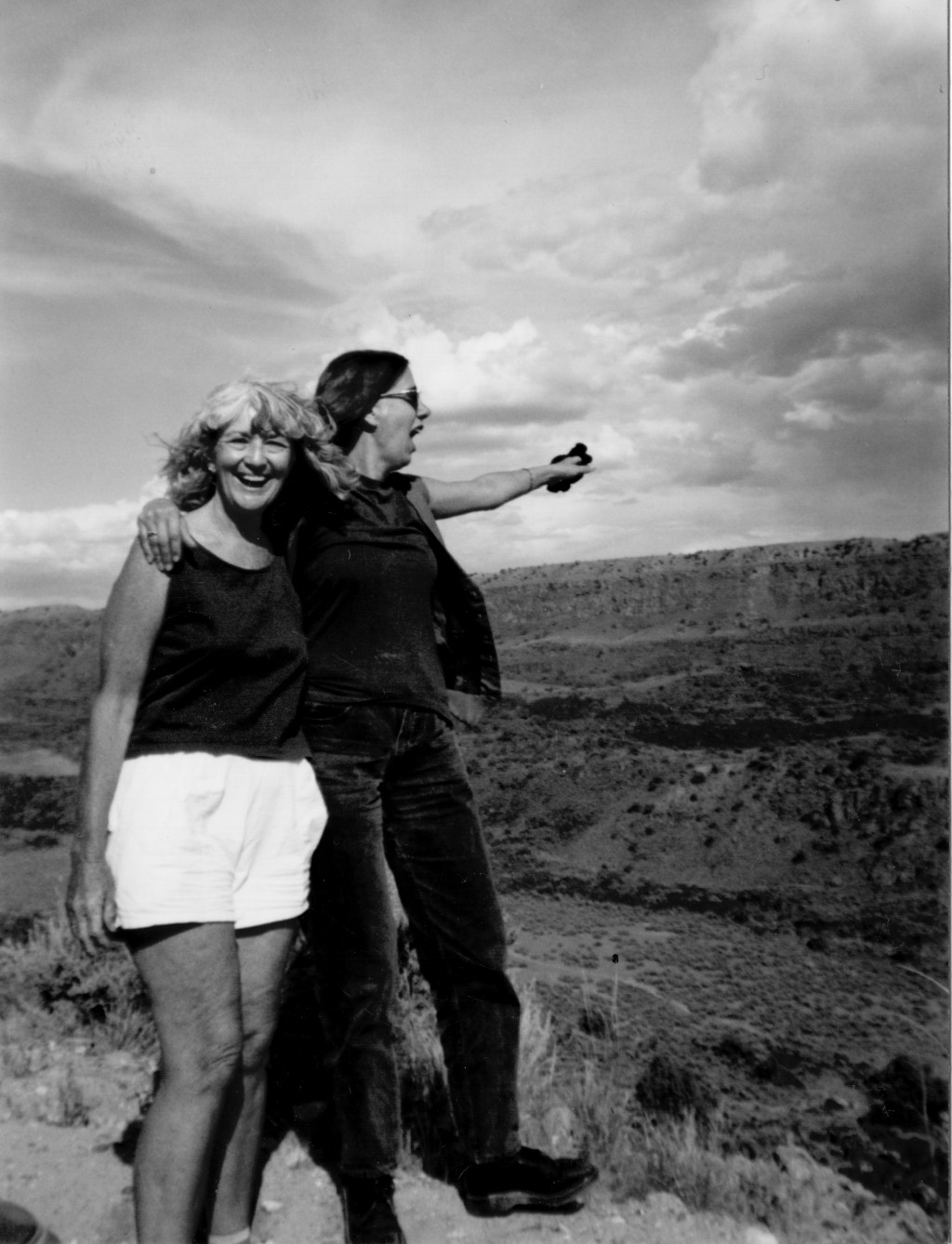

Luanne

You were a therapist married to a psychiatrist. You were reading Lacan and writing about your patients in your dissertation, patients with difficult mental patterns. At the time, I was in a Lacanian reading group. Your writing was experimental, almost literary. There was a way your mind joined the minds of your patients, and I found that interesting. You asked me to be on your Ph.D. committee and the first meeting was held in Taos. Afterwards, everyone went to Ojo Caliente hot springs. I loved New Mexico. Several times, you came to NYC and I visited you in Taos. Once you took me into the desert to meet Louise Bourgeoise’s son, Jean Louis. He was living off grid with no public services, no address, no taxes. I remember the fields of sage surrounding his house. I fantasized about living like that. Several years later I did live in New Mexico for a year, but not off-grid. I remember you didn’t like my boyfriend, a philosopher who never arrived on time for appointments, sometimes an hour or two late. He drove me crazy. I watched you flirt with him, well maybe it wasn’t flirting, but it seemed like it at the time. You both had a tendency to sexualize your gestures and expressions, maybe for you the result of childhood trauma. Then you insisted on not revising your dissertation, essentially pitting me against the head of your committee who was also a friend of mine. Why was it so difficult to follow guidelines that you had created? Maybe it had something to do with the fact that as young women, Mary was a nun and you were a sex worker. The last time I stayed at your place, I felt as if I couldn’t breathe. I remember you standing behind a door, listening as I made a phone call. I was trying to change my plane ticket to go home sooner. After that, I stopped seeing you. Now I ask myself a question a therapist once put to me—What part did I play in that which I bemoan? Even now, I’m not sure.

Marie

We lived on the same block on 9th Street near the park, and our boys went back and forth between our apartments, looking for a place with no parent around. We were always on alert to put a stop to some of their plans—dropping water balloons off the roof on passersby, that kind of thing, throwing vegetables into the neighbor’s yard in the middle of the night and so on. We were both strapped with big student loans. Once we had a meeting in your apartment with a few others about forming a coalition to fight for student loan forgiveness. We put an ad in the newspaper, but for some reason, we never followed through. I remember riding our bikes south on Ocean Parkway, heading to your aunt’s house in South Brooklyn where you had grown up, but I got a flat tire and we had to walk our bikes back. You came to some of my poetry readings, even though poetry wasn’t your thing. Once you made a presentation to a class I was teaching; we were reading Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, and you talked about the prisons in New York, how crowded and hopeless the situation was for the inmates. We celebrated the children’s birthdays together. The one I remember most is Linnée’s 16th. She didn’t want a party, but I made a cake for her. You and Armando came over, Allen and Mook were there, too. But Linnée refused to come out of her room. We stood at her closed bedroom door holding the cake and singing to her. It was hilarious. Then the kids got older. “That went by so fast,” you said last night on the phone. Eventually, I turned our 9th Street apartment over to Allen, and you left your job in Criminal Defense at Legal Aid and moved to New Orleans to defend people on death row.

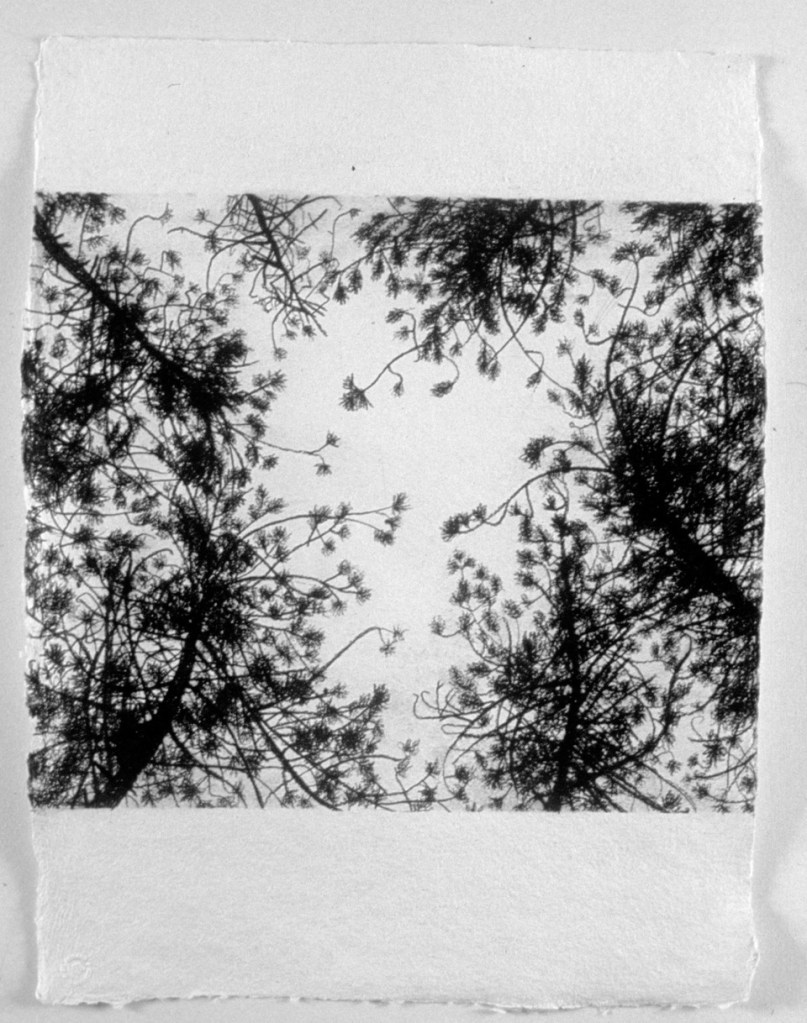

Georgia

In the middle of the cavernous Catskills, we took off our clothes and hopped around on the stones in the river, taking photos of each other, reclining, standing, and you made the photos into two collages, each like a hand of cards. You carefully removed a fanshaped mushroom from a tree in the forest, then etched a tiny tree branch on its side, and gave it to me. At the art colony you were studying the sky, drawing treetops on white folded Japanese paper, and under the wild trees and in the wind while watching you draw, I wrote a series of collaged sonnets. Everyday we escaped down the road to an open air aikido dojo where we learned how to fall down, roll over, and stand up. In Provincetown, I stayed with you at your cottage, showered on the porch, swam and walked along the shore. I remember sitting on the beach reading Moby Dick and taking notes for a long poem I would later write. When Allen died, I came to you in grief. When you were in the hospital for a surgery, I helped you shower and wash your hair. I always loved sharing your relationship with space. Even the table setting brought a sense of quiet and peace, a way of distracting from the losses we encounter in life. I watched you working day by day in your studio and I brought some of your discipline and sensibility into my own life and art. After you married, you were often in Rhode Island and Paris, I was in India and out west, and we rarely saw each other, but I remember once sitting with you outside Café Orlin while we watched the pouring rain gush over the awning onto the sidewalk and street.

Julia

I once taught a class on American lit and melancholia and I included your book, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. When I gazed at the black and white print of Holbein’s painting of Christ in the tomb, it was as if I was standing at my mother’s bedside looking at her body. Jesus, she told me, had appeared in the hospital, calling for her. Here he is flat-out dead, cast aside, mortal. Holbein must have suffered to paint him like this—Father, why have you abandoned me? I’d been mourning my mother for years. You are going in circles, our analysis is not working, my therapist said. Well, if I’m going to suffer like this, I thought, I might as well enjoy it. I wrote a novella, Black Lace, about a young woman whose parents had abandoned her, and how as an adult, she tried to free herself from identifying as a victim. Some years later when it was published, I opened the novella with a passage from your book: “Melancholia belongs in the celestial realm. It changes darkness into redness or into a sun that remains black, to be sure, but is nevertheless the sun, source of dazzling light.” I wanted to give the reader a hint of light. Perhaps you did, too, after all, you are an analyst who believes in the possibility of change. By then I’d already snapped out of my intermittent love affair with loss. How? Not through analysis, at least not directly. When I started practicing yoga, the breath work and movement pulled my mind back into my body. A reminder, a tattoo I wanted, but never endured: My body is my home. For some reason, I found that idea incredibly freeing.

Below: Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb” (1520-1522).

Harryette

Lorenzo Thomas and I stopped by the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. You were there with your sister Kirsten. “You should ask Harryette for work for Long News,” he said. “Her book, Trimmings is wonderful.” I loved the dance of fragments, the playfulness, the celebration of femininity, experimental, language luscious and politically charged. For some reason, you and I hit it off immediately. We almost bought an old adobe house together in Las Vegas, New Mexico. But the town was so small. Could I find work there? My children and friends were in New York. Would I like it? Would it need a lot of repairs? A second home for you, but my primary space. I could never go back home to NYC if I owned a house out west, and I’ve always liked moving around. Eventually, I chickened out. In 2009, we talked for hours on the phone about the poems in Sleeping with the Dictionary, and we turned our talks into a book. Once I stayed with you in LA. We cruised the city photographing for our book—the neighborhood in Crenshaw, Robert Graham’s sculpture garden at UCLA, Watts Towers. When I recall your house, I think of burgundy. Is that a favorite color. Many meetings over the years as we crisscrossed the country, and long periods of silence, too. Then someone stirs my memory with an email, like last week— Do you know how I can reach Harryette Mullen?—so I send you a text and you call me back. And we catch up as if no time has passed.

Gloria

We met at the Kaveri Inn on a dirt road in the heart of Mysore. After morning yoga, cross-legged on the floor in front of the Ashtanga guru, Patthabi Jois, we rolled our eyes as he asked for chocolate and American money. You spoke Spanish but knew some English. I spoke a little Spanish. In the Indian restaurants while eating idli and curry, we pretended we were in Paris. You had married a French man once and lived in Paris as a dancer. I had just broken up with a philosopher who loved everything French. You could walk right into the most frightening Indian traffic and the vehicles and cows would weave around you. You made a sculpture in the courtyard with Indian artists who were carving statues of Hindu gods. In Puerto Vallarta, I visited you and we swam with the crabs, went to your art openings, traveled with your boyfriend into the countryside, and fasted on black grapes. I took your yoga classes and wrote about you in a photo poem pamphlet. I gave you a copy, but I was never sure if you liked it or not. A poetic word collage can make for misunderstanding. After I moved to Tucson, on Christmas Eve, you called me from your parents’ house in Nogales. You wanted to talk, and when I was home, I tried to call you back, but after that, I couldn’t get a line through. For two days I couldn’t get through. And then you were gone. Too many people calling from Tucson to Mexico on Christmas. Perhaps you thought I was dissing you. Inadvertently offensive. A translator needed. Many translators. No response. Tangled lines. And that’s how we lost each other.

Miranda

When you moved from Detroit to NYC, you volunteered to help with Long News and then you became the art editor. We spent weekends in the galleries looking for visuals and talking about theory and politics. You made covers for many of my books—a spooky Dürer engraving of a devilish guy with a skull coat of arms and wings tempting a woman with carnal pleasure; in shadow a woman (isn’t that you?) photographing a tree with an open book in the branches; in the corridor between your house and your neighbor’s, dark blurry figures strolling forward and back. Once you were collecting objects that held guilt, a ritual—a Mother’s Day card that Allen had given me after we broke up; I’d behaved badly and thrown it at him. I’ve always felt guilty about this. Even after you cut it up and burned it, I still felt guilty. I remember once lying on my bed calling stores and restaurants to try and find a pair of lost glasses, while you photographed my belly button for some project. You clipped 999 corners from my books, and I collected a line from each one, making 72 sonnets, My Autobiography. A triptych of your bird nests is on my wall. In the mid ’90s, you started practicing Ninjutsu and I started with Ashtanga yoga. You tried to help me with my difficult cough, teaching me some qigong breathing. You loved my dog Dorothy, and you took a photo of us for the cover of Me & My Dog. You’ve always been an animal lover. Several lost cats have found home with you. We’ve both had a lot of losses over the years, and a couple of minor fallings out. Even though once in a while, we make each other crazy, we’ve worked together on many projects, and not long ago, we promised each other to stay friends forever.

Left: Dorothy and Miranda Maher, 1999, photo by Barbara; Middle and right: two of many book covers designed by Miranda.

Julie

One hot night in 2010, we met for tea. You talked of an acupuncturist who had helped your mother with her breathing. I made an appointment and then he and I were involved for five years, living together in my small studio with his young son. When you were out of town, I found a quiet retreat in your apartment. Sometimes you came over for dinner with us. When we broke up, you consoled me. One of your collages is on my living room wall, a dress with leaves and bits of flowers and odds and ends, antlers for straps, with no head but ankles and shoes, as if a fairy had hung up her dress in the field. Once in your place in Cleveland, I stood at the window looking down on you in your garden, chatting with neighbors and tending to the plants. I took photos of your artwork, found objects and sculptures made from discarded junk. Everything about your life is part of your art. I talked to the Belladonna board about how wonderful your emails were, that we should make a book of them. I photographed you at several readings, and we read together in Detroit a few times. In your sensuous improvs (making-do you call it), you pull words, syllables and phrases right out of the air, like scatting, some jazzy hybrid between song and poem. Some poets struggle for a line, but not you. For you, everything bumps against everything else and blossoms into something different. Open an old refrigerator and you’ll find a flower garden. After you gave up your apartment in the city, on my travels back and forth from Detroit, I stopped a few times to hang out with you and Arcey. When Covid descended, our rhythms hesitated, not for a month but for a couple of years, and now we’re older and I’m not doing much long distance driving anymore. I do miss seeing you. I open my last email from you, sent on September 18, 2021, and I laugh out loud.

Barbara! I squeeze you tight with all my might

And catch you in NYC soon soon swoon

Before the shivery moon

Love you!

jlp

Martine

I met you in the ’90s after publishing a poem of yours in Long News—mythic, spiritual, experimental, a narrative repeating, transforming. I remember sitting together at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. When I sent my interviews of Harryette Mullen to Belladonna, you volunteered to edit the book, and we worked together closely on the project. After spending so much time discussing Oulipo, we decided to write a series of poems together. 14 lines a day, 14 days, on 4 x 6 cards with 14 lines each, later published together in Peep/Show. I visited you a couple times out in Montauk in the summer. I remember taking HD’s Notes on Thought & Vision off your shelf and reading some of it to you while we sat on the beach. “The love-mind and the over-mind . . . properly adjusted, focused, they bring the world of vision into consciousness.” We read together once with Rachel Levitsky at the hidden library on Jersey Street. The last time I saw you, you were reading your poems online for Tucson’s Poetry Group, and then before that, reading parts of my novel, again online for the Brooklyn Rail. Before Covid hit the city, made all the poetry readings take place on zoom, and kept us home alone with Criterion, we used to meet for dinner and films. For some reason Melancholia stays in my mind, the planet heading toward earth, the end imminent and everyone praying and preparing. As we walked back to the East Village, we kept looking up at the sky. Once when I was hesitant about getting involved with someone because he had a child and I’d already raised two children, you said something profound, sharing your Buddhist knowledge with me—You never know, Barbara, that child might become the most important person in your life. Eventually, I lost the child, or he lost me, but if you had not said these words, I might never have loved in the way I loved.

Jane

Harry Mathews wrote me a letter in 2011 comparing my novella, The Dinner, to your Two Serious Ladies. About your book, he wrote, “It’s one of the brightest stars in my constellation of masterpieces.” About mine, “It’s an utterly captivating work (captivating = gripping, entertaining, impossible to stop reading, compelling, nifty).” In your novel, your characters make U turns and zigzags. In your letters you ridicule your own suffering and indecision, and you seem unable to come to a decision about the most insignificant issues, constantly overwhelmed by multiple possibilities. You loved women, yet constantly nodded to Paul. His writing came first, and you were very insecure about your own. But your writing is so splendid. To decline. To be less than needed. To fall short. After a while, your friends became embarrassed you might lose control. When you were a grown woman, trying to hold on to your sanity, your mother called you “my little princess.” After you died, the doctor explained, “For her it was fatal, the early life of pleasure, the drinking, the excitement, given her sensibility.” As I’m driving on I-10—the big trucks and trains passing by, far distant horizon and jagged mountains—I think about you, like a child, but an adult. Maybe things would have been different if you had not always been provided for, maybe if you had to make a living and provide for others. I wonder if there aren’t some benefits to economic necessity.

Nancy

For my ex-partner, the word “boyfriend” signaled disrespect. I had not experienced racism as he had. For me the word was looser and more joyous than partner or man friend; it was intimate, the child in the man. A minor difference, one word, but in our five years together, there were paragraphs, chapters and volumes. Many loving moments, of course, but after a while I couldn’t calmly respond to his mood swings. I needed help. You were my age, single, sensible, years of experience as a psychotherapist, and hip at the same time. We had practiced yoga with the same teacher, and we knew many of the same people. Quickly, you picked up on what I already knew. Even though I loved him, I couldn’t take a chance that seemed so slim, and instead end up ruining my final years. You helped me sort out many of my mother-loss reactions and fears. I would have left eventually, but I was relieved to have you at my back, helping me. You read my books as I was writing them. You came to my book party for Just Like That. You’re still there for me when I’m in a quandary or I lose my cool and I’m blown around by my emotions. You understand what it’s like to lose someone; you had two sons; one died when he was a young adult from an auto immune illness. You know what it’s like to live with a respiratory illness like mine. I’d bike up town on 1st Avenue to your office, and we’d sit together with your puppy curled up at my feet. Now if we talk, it’s on zoom. We often wavered over the line between friendship and therapy. For a while, I did your accounting and gave you yoga privates. When my son’s wife was suicidal, you met with them, but she refused to return. A few years later, when she took her own life, without hesitation, you were there for my son. You became his therapist and spiritual guide. Om Nama Shivaya. From one mother to another, Namaste.

Barbara Henning is the author of four novels and eight collections of poetry. Her most recent book, Ferne, a Detroit Story, is a novelized biography of her mother and the city of Detroit (Spuyten Duyvil 2022, Notable Book Award, Library of Michigan 2023). Girlfriend is forthcoming from Hanging Loose Press (2025).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.