Being a documentary filmmaker is a bit like trying to play God. They must embark on an agonizing process of creation, sifting endlessly through old interviews, letters, journals, and other raw archival bric-a-brac, cutting and reassembling the disparate bits and pieces until they merge into a single coherent narrative. The reward is that, under the right circumstances, the filmmaker can wield the ultimate power: the power to shape a viewer’s perception of reality, what really happened.

That’s the ideal. But as any seasoned creator understands (or should), perception is a slippery beast. It doesn’t take much for their efforts to fail, no matter how well-intentioned.

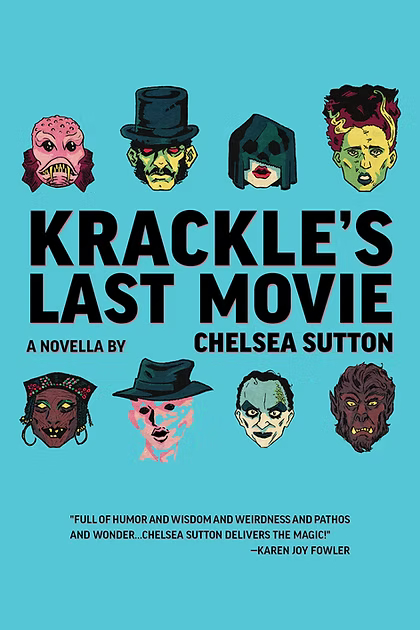

Krackle’s Last Movie, the recently published novella by Chelseas Sutton, offers a delightfully weird exploration of the promise and peril lurking within every documentary. The result is a deeply original if not deliberately vague meditation on how movies, identity, and even time itself are constructed.

The story begins in 2019, just after the unexplained disappearance of would-be documentary auteur Minerva Krackle. Twenty-two years earlier she released her first and only completed film, The Monsters Are Here!, chronicling the emergence of “werewolves, invisible people, vampires, and more strange and complicated shifts in human anatomy” throughout the United States between 1972 and 1997. The documentary earned almost no public recognition apart from a mocking segment on a local morning talk show, during which the smirking, oblivious hosts mistake it for a narrative film; one of them praises Krackle’s vivid imagination and marvels at how “pathetic” her interview subjects are. Misunderstood and broke, she fades into further obscurity and takes on work as a custodian.

But, like any true obsessive, she finds it impossible to set aside her passion, and she resolves to direct a new and final film: a documentary about her own, monster-chasing life. At the time of her disappearance she is two-thirds of the way through postproduction, and responsibility for completing it falls to the book’s narrator, Harper, Krackle’s assistant and camera operator.

A monster herself, Harper came into Krackle’s orbit after writing a letter of appreciation to the filmmaker for making The Monsters Are Here! and its acknowledgement of “people like me.” Helping her finish the film and track down the missing director is Dr. Danger, a friendly, Freeze Ray gun-wielding supervillain who Krackle interviewed in Monsters and subsequently became her bodyguard. (Many of the whimsical character names feel like a cross between a vaudeville star and Pynchon character.)

Despite deciding to work with the world’s most foremost—and possibly only—monster documentarian, Harper is deeply conflicted about her identity. She started growing wings at a very young age, but since she was four has been cutting them off as soon as they grow large enough to be noticed through her shirt, leaving two bloody stumps in their place. In one of Krackle’s old journal entries, she describes asking Harper why she does this. “They’re not natural,” Harper responds. “I ask her what she means by natural,” the entry continues, “and she says, you know, normal and so I ask what she means by normal and she says the thing that keeps you invisible.”

All of this looms in the background as we watch Harper attempt the impossible task of finalizing someone else’s autobiography. Mirroring the frenzied, herky-jerky atmosphere of the postproduction editing process, the story whipsaws between Krackle’s old audio and video interviews, her personal notes and journal entries, and found footage, all while jumping between past and present. The effect is disorienting and stressful, highlighting the yawning gap between spools of random source material and a slick finished product, chaos and order.

We learn that Krackle became interested in monsters after the first five cases of “beastification” were reported in the United States, in 1972. At the time she is twenty-five, and her irrepressible curiosity motivates her to arrange an interview with a vampire on the New York City subway (albeit in his “normal”-human form). Other characters we meet in the book include a “modern-day mummy of San Bernardino County” whose sister may or may not have disposed of their arms and feet so they’d finally get some eternal rest; a sea monster who works at a hardware store; a popular magician who dies during an escape performance; a haunted tract house; and an invisible dancer who once toured with Alvin Ailey, to name just some of the nearly dozen minor oddities.

All of which is to say, despite the novella’s short length, there is a lot going on narratively and thematically. One result is that Harper’s journey of self-discovery, the subplot that could potentially provide real dramatic depth, feels somewhat overwhelmed. The book’s huge (monster-sized?) ambition is simultaneously its biggest strength and its biggest weakness.

Is Krackle’s Last Movie a satire of documentaries? In their drive to make a compelling film, is it inevitable that directors exploit their subjects, turning them into “monsters” for the public to voyeuristically consume? Or is it an allegory for being an outsider in a world full of “normal” people? A reflection on the formlessness of time (which is capitalized throughout the book, hinting at its importance) and the futility of our attempts to harness it via pat narrative? A feminist and/or trans allegory? A clever new twist on Frankenstein?

It’s hard to say with certainty, at least for me. On the other hand, my sense is that the ambiguity is the point. Once a filmmaker’s—or, for that matter, author’s—monster is released into the world, despite their pretensions to play God, it is no longer under their control. The best they can hope for is that it isn’t forgotten.

“[Krackle] is not here,”a voice in a haunted house tells Harper and Dr. Danger, during a trip they take to locate her two days before their film is due. “But pieces of her were left behind. Every interview she had. A small piece of her unlatched itself each time she absorbed someone else’s story.” Not literally. I think.

Krackle’s Last Movie, by Chelsea Sutton. Ralston, Nebraska: Split/Lip Press, February 2026. $18.00, paper.

Adam M. Rosen is a freelance book editor and writer in Asheville, North Carolina. He has contributed to TheAtlantic.com, the Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Review of Books, the Baltimore Sun, the Onion, and many other print and online outlets, and is the editor of the essay collection You Are Tearing Me Apart, Lisa!: The Year’s Work on The Room, the Worst Movie Ever Made (Indiana University Press, 2022).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.