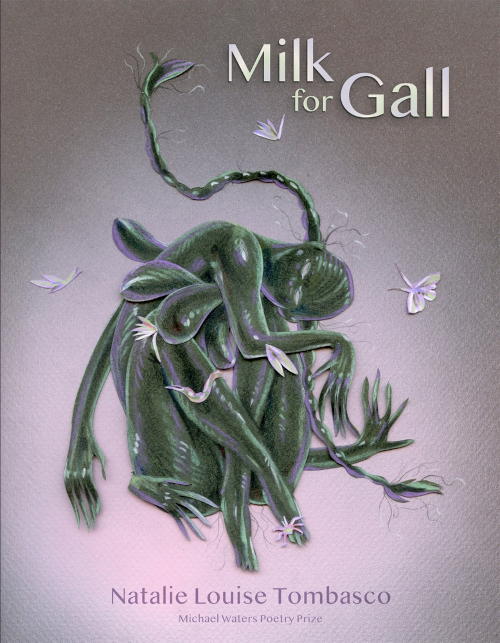

Natalie Louise Tombasco invokes Shakespeare to great effect in the title of her debut collection, Milk for Gall, by promising the gamut from comedy to drama and delivering it all with aplomb. The collection’s title comes from the famous speech by Lady Macbeth in Macbeth Act I, Scene V, in which she declares, “Come to my woman’s breasts, // And take my milk for gall,” preparing to disavow her prescribed maternal role for the murder of Duncan so that her husband Macbeth may seize the Scottish crown. Her character is infamous for fantasizing about infanticide, declaring that she would have “dashed the brains out” of her nursing child to accomplish these goals. Like Lady Macbeth (save the murderous desires), Tombasco doesn’t shy away from ambition or bold condemnations of the motherhood thrust upon young women by virtue of female anatomy. Through the title, Tombasco suggests that this book—a product of herself as much as breastmilk is of a nursing mother—may provide relief from irritation, like a salve on the chaffed skin of domesticity. And in true Shakespearean form, the book’s title contains a double meaning, as gall also recalls the well-earned impudence of women who speak their unabashed truths. Tombasco forces her way onto the metaphorical throne by usurping cinema, literature, and modern-day memes with a cutting wit and stomp-and-holler musicality.

The prologue poem, “Drawbridge + Moat,” is a microcosm of the collection’s ultimate structure, a nod to the guarded castle which houses an archetypical princess, a damsel in distress waiting to be saved. She begins the poem “with a primordial sigh,” much like Gaia, the mythic personification of Mother Earth, before drawing a connection to Sappho in the same breath, linking “The Poetess” in this chain from history’s first mother to its last. As such, Tombasco is inviting us across the drawbridge at our own risk. While we luxuriate in the parabolic milieu, Tombasco actively subverts any fairytale trope and even tempers her own expectations of a royal legacy when stating, “Queenhood will breed grave dis- // Appointment.” In considering queenhood, Tombasco attempts to reinvent her lineage from poets like Emily Dickinson by saying “My sex is a semicolon—,” a use of the em dash here in both homage and deviation. This recontextualization is continued throughout the collection in her “Dream Vision” series, in which she “playfully repurposes the writing of influential poets,” according to the book’s end notes. This playfulness, however, is more than just a repurposing. It is the reconstruction of over-studied inspirations from Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, and Sylvia Plath, as well as gay men poets like Frank O’Hara and Allen Ginsberg, hinting at the collection’s diversion from gendered stereotypes to a queerer representation of Tombasco’s identity as a woman.

The collection is sequenced into three sections: the “Concrete Realm, the “Spindle Realm,” and the “Bulb Realm.” Tombasco moves through these sections and traces a poetic evolution in both form and content. The first section, the “Concrete Realm,” contains the poems most grounded in narrative technique, as well as the poems focusing on Tombasco’s adolescence in the epitomic concrete jungle: New York—more specifically, the oft-forgotten borough of Staten Island. She addresses her suburban upbringing by asking “what have you given me // besides the rotten bottom of the pot,” recognizing that “[its] love is hypodermic, full of wreckage.” The Staten Island Ferry acts like the aforementioned drawbridge by giving Tombasco an escape from the “lowbrow meow, blue-collar slang, all the Wu-Tang-loving white boys // on The Island” to the bright lights of Manhattan, its “alliums // in Battery Park” and “bronze snout of Charging Bull.” But between the midnight meanderings from the Brooklyn Heights Promenade to her Q Train stop, Tombasco grows into her womanhood and sees a future where “paradise has gone tasteless as a stick of Juicy Fruit.” She begins to understand that “Shitshow Barbie” is made from the same plastic as Pregnant Barbie, lamenting “why did you manufacture me this way?” In the poem “Bees!,” Tombasco embodies Lady Macbeth through wordplay and enjambment, ordering us to “blame the husbandry” and confessing “I squeeze the life out // Of a plastic bear.”

Life breaks through urban concrete in the “Spindle Realm,” but Tombasco wants nothing to do with it. “Waking up is foul milk,” says one poem, and Tombasco knows it, so she continues to dream and advises us to do the same. She is no longer pulling punches when she says, “childproof your insides,” eschewing any nurturance of a life not yet fully lived. In poems like “Down, Down from Fenneltown,” “The Girl with the Appetite of an Ogre,” and “Viciousness in the Kitchen,” Tombasco takes the lessons from her mother and uses them to feed herself, replenishing a soul still burgeoning in its own right. Avoiding society’s clamoring for her bulb, Tombasco creates these realms to adventure and push back against unseen evil forces. In a pair of poems referencing Lolita, the eponymous character in Nabokov’s novel, Tombasco is perhaps suggesting that she, too, is still sporting “schoolgirl slacks” and a “Dutch braid slithering between knob knees.” In “Lolita Licking Wounds,” the collection’s final poem, Tombasco voices what is inherent to all women poets: “Our art // must be fanged, yellow-eyed, & preying.”

That poem ends, however, with recognition that “the language lent here will outlast you,” as it will the poet and the book. Similar to the remaining milk in a bowl of cereal, this magnificent collection is a treat of vibrant colors and sweetness, a libation for a reality that, without poetry, would be too hard to swallow.

Milk for Gall, by Natalie Louise Tombasco. Evansville, Indiana: Southern Indiana Review Press, December 2024. 84 pages. $18.95, paper.

Matthew Zhao is a poet from Michigan, now a PhD student at Florida State University. He was a finalist in the National Poetry Series and Mississippi Review Prize, and a semifinalist in the Word Works Washington Prize, Longleaf Press Book Prize, Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize, and Autumn House Press Poetry Prize. His poems appear or are forthcoming in swamp pink, Four Way Review, Frontier Poetry, Summerset Review, Indianapolis Review, Shade Journal, Ibbetson Street, BoomerLitMag, PRISM International, Diode Poetry Journal, Good River Review, Pinch, and elsewhere.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.