When Luke Cole goes missing, everyone blames his father. Classic case, folks mouth around town, in line for their lattes, their postage stamps, imagining how an estranged ex-husband might abscond with his own son to torment the kid’s mom. Most figure Luke will turn up in a week or two, sheepishly clutching a body-warmed Big Gulp and wearing the same ratty T-shirt he was last seen in.

But then Billy Reynolds goes missing. And Troy Anderson. And Langston Tsegaye and Chance Jarvis and Tuân Phạm. Every few days, another teenage boy vanishes from Sullivanna’s streets. That pretty much clears any question of Luke’s dad but introduces a lot of other questions no one in town wants to think about.

By the time Eli Hochstetler disappears, the story’s been picked up by national media. Every corner of downtown is occupied by some foamy-mic’d reporter getting tangled in the town’s syllables and spouting a different theory about the so-called Sullivanna Six, tripping local old ladies with their production cables snaked across the sidewalk. Folks can’t turn on the television without seeing the boys’ faces. Missing persons flyers blow from streetlights and storefronts, into storm drains, only for passersby to put them right back up again. As though everyone in town doesn’t already know who’s missing.

The Sullivanna High booster club hosts self-defense classes, seven dollars per head.

The multi-level marketing moms hold a workshop on essential oil-based safety spray: garlic, turmeric, black pepper, vodka.

The Sullivanna movie theater opens early on Fridays, playing back-to-back showings of Zodiac all weekend long on their single screen.

A neighborhood watch forms; dads in utility vests sign up in groups of three to circle Sullivanna’s residential streets, tepid coffee sloshing over the lips of their camping thermoses. Mothers double and triple-check their deadbolts at night.

It appears the boys were taken from the same cross-section of town. If taken is the word. There are no signs of struggle. No windowless vans sighted. No suspicious characters skulking.

Most critically, no bodies have been found either.

#

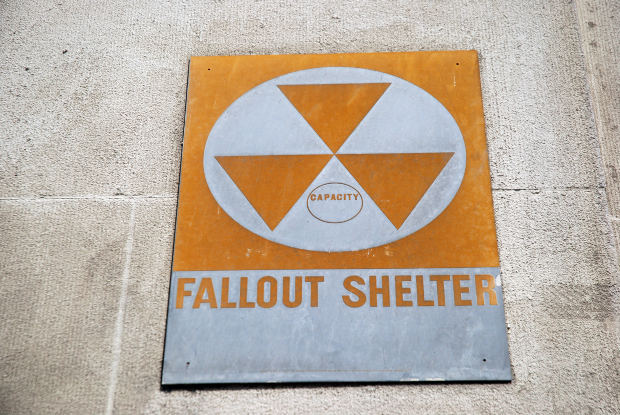

The afternoon Eli Hochstetler disappears, 12-year-old Jenny Young is the first to know. The previous summer, she and her mother moved into the raised ranch just down the street from Eli, on East Eberhart—the one with the enormous catalpa tree out front and a Cold War-era fallout shelter beneath the backyard, which the previous homeowners promised was backfilled.

Only Jenny knew it wasn’t.

The afternoon Eli vanishes, Jenny rides her bicycle past his house on her way to the 7-Eleven. It’s unseasonably warm out, one of the last days before autumn shreds into winter. Eli, hearing the flurp of the playing card Jenny has clipped to her bicycle spokes, turns briefly from his basketball hoop to notice how her ponytail unfurls from the base of her skull, a cephalopod snared to her cervical spine. And Jenny notices the terrible electricity of noticing Eli’s noticing: a sparkling through her chest, the bicycle seat hot and hard between her legs. A jolt. Hunger.

The afternoon Eli vanishes, Jenny rides past his gaze. Then, she doubles back. Her bicycle’s front wheel noses his driveway; fine hair rises on her legs as she stands tall on the pedals. Jenny curls her mouth into a smile and asks Eli if he wants to see something cool.

#

The moment she first set foot in her new backyard, Jenny knew the fallout shelter hadn’t been filled as promised, her senses a churning negotiation between foreboding and excitement. Circling the lidded hatch—unremarkable as her mother’s cookie sheet, hidden in the grass between the privacy fence and the windowless side of her house—the more certain her instinct there was something other than loose earth beneath her.

The lid was thick steel, costing bruised knuckles and bloodied fingernails to lift. An overripe exhale met Jenny’s face. Descending the narrow ladder, she’d expected dank, icy darkness. Instead, she found heat and heartbeat, a cloying carmine glow. More womb than bunker. And in a corner, something. An undulating, velvety and tendrilled. Leviathan-like. Fluttering, as though through water. She could feel its want, a hunger Jenny recognized.

All summer, Jenny made offerings to the shelter: mice, snakes, small birds, anything she managed to trap in the yard. She tried feeding it Mrs. Ostrovsky’s perpetually unleashed terrier, which she straddled, then strangled, late one night with headphones on and her eyes shut tight. She even surrendered herself once, nakedly stoic against the concrete floor. The appetite grew shrill.

It is the thing in the corner of the fallout shelter that teaches Jenny what to do with hunger. How to let it roil through her until craving isn’t something she feels, but what she is. Observing its deadly tender ministrations, she learns: move like this. Squeeze this way, harder. Bite here.

After Luke, the others were easy—easier. A flip of her ponytail. A wriggle in her bike shorts. What teenage boy won’t follow a girl with something to show them? All she had to do was recognize what she’d been ignoring all along: the pulsing, slurping, writhing just beneath the subsoil of her backyard—it only wants boys.

#

What Jenny hadn’t anticipated was Eli Hochstetler’s younger brother, Owen, following them. His tangle of limbs landing on the concrete, his eyes growing to teaspoons in the glow. His shock at having fallen down the last few rungs of the ladder replaced by a greater one at the thing holding his brother. What is left of his brother.

The shelter, which grows impossibly hot during a feed, cools at the disturbance. Jenny shivers. And there is a different feeling in the air now. Anger. Satiety interrupted.

Pressure builds at Jenny’s back, a tectonic rumble. Metallic breath slicks her neck. It wants her to deal with Owen, she realizes. To do what’s been taught.

Jenny hesitates. There is a difference between feeding and being fed. At least, that’s what she’s told herself—that she’s only making offerings, the hunger she’s satisfying isn’t her own. That she doesn’t want anyone to die, not really. She just wants what is in the shelter to live more.

She vacillates too long. Only a second, a couple shallow breaths, but Owen is no longer at her feet. Jenny is suddenly aware of the tremendously narrow space, how much more dirt there is than air around her. In Jenny’s ear, the titter of rows and rows of teeth drawing open, shut, open.

Jenny lunges for Owen’s arm on the ladder, finds an ankle instead; her fingers grasp at soft hairs, the hem of a pant leg. Then, just ladder. Above her, a scramble, before the lid edges back over the hatch, the light tapering in slivers. Owen—so much younger, smaller than his brother, than even Jenny—is struggling. Jenny knows she could be up that ladder in a flash.

Her hand is still gripping a rung when Owen finally thuds the lid in place. For a moment, there is silence. Jenny turns to face the shelter, her heartbeat in her ears. The cloying carmine glow closes in around her. She feels her blood begin to scald.

E Ce Miller is a storyteller from the American Midwest living in South Korea, where she’s writing collections of short fiction and a novel. Her work has been performed in the Liars’ League reading series in London and is published in Bustle, Culture Trip, Midwestern Gothic, The Sun Magazine: Readers Write, Pacifica Literary Review, and elsewhere. She is on the nonfiction team at indie publisher Split/Lip Press and the fiction team at Four Way Review.

Image: kconnors, morguefile.com

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.