Information theory defines its index in terms of the likelihood of being able to predict the next symbol in a sequence. Counterintuitively, the highest information density appears where a string is entirely random. Given the letters “ajhhjnyv … ,” the next character could be any of the twenty-six options available on a standard keyboard. By contrast, if the sequence begins “imperalis … ,” then the next letter is very probably one of two possibilities (“t” or “m”).

If you and I are speaking out on the street, and a truck goes by at this point, you’ll most likely still get the gist of what I’m saying. Ordinary speech contains a lot of redundancy, which enables us to understand each other in a noisy environment. We don’t want to max out the information content of an everyday utterance; we need speech to be less fragile, to resist breakage.

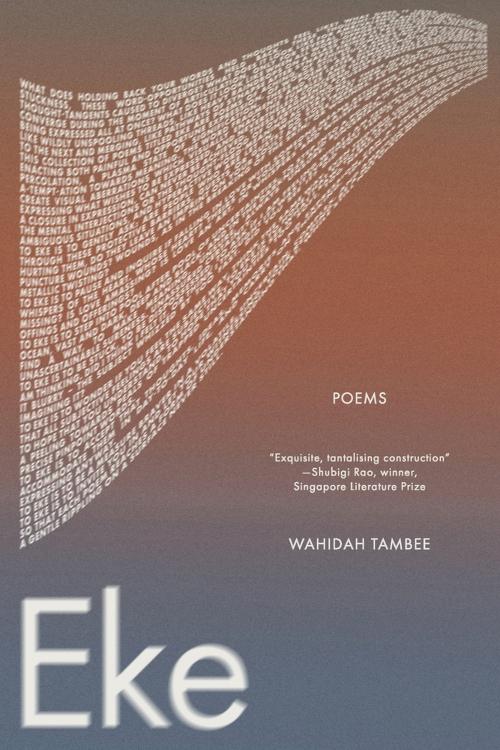

Eke exploits the uncertainty that exists where a word might branch in more than one direction. Wahidah Tambee creates amorphous typographic clusters on the page, their shapes recalling Rorschach ink blots and likewise allowing for a range of individualized interpretations dependent on the subconscious orientation of the viewer.

These pieces are listed by title in the table of contents, but are not titled on the page. This choice enables a clean encounter with the poem as a visual form, with its negative and positive space. It also makes the titles into a sort of open secret, a bit of minimally concealed information to be sought elsewhere, in keeping with the themes of the material around that which is said, unsaid, heard, and unheard.

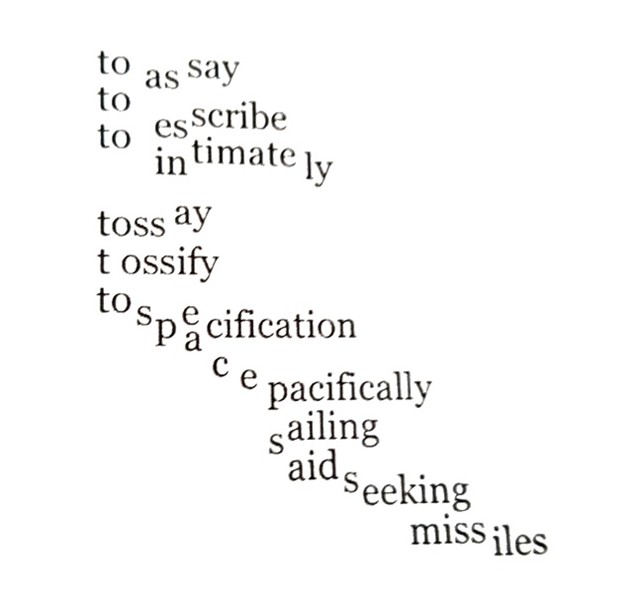

The piece reproduced below is titled “said sail”:

Various readings occur: “to say” or “to assay,” “to scribe” or to “to ascribe,” “to estimate” or “to intimate” which in turn folds into “intimately.” Further wordplay interleaves “specification” with “pacification,” “pace” with “peace,” and associates “pacific” with “sailing,” then “sailing” with “ailing,” and “said” with “aid.” Finally we slide into violence with “seeking” (or “eeking”?) “missiles.”

In the book’s afterword, Tambee outlines her construction of the term “to eke” in terms of “stuckness” and collision. “These fragments and displacements … recreate the mental interjections or the thought-flood of overthinking caused by polysemantic words, ambiguous situations, and hyperactive word-meaning activations. … To eke is to step into pool after pool of uncertainties, to step into a pool and to discover it is an ocean, vast and dark, deep and black.”

Tambee completed a degree in psychology before pursuing further studies in Nanyang Technological University’s creative writing program. In Eke, she explores linguistic processing from a psychological perspective, observing brain states in action. “To eke,” she explains, “is … to ask if I am feeling what I am feeling, thinking what I am thinking. Did I think I felt it, or think I thought it? Was it ever there? … Did you see it? Did you feel it too? Or am I just imagining it?”

The poems in Eke work within the frame of the English language. Tambee’s home country of Singapore is a multilingual environment, with official languages of English, Mandarin Chinese, Malay, and Tamil. There’s also a commonly spoken creole called Singlish. We don’t see these other linguistic influences prominently on display here, but the presence of multilingual speakers and differing levels of English-language fluency has relevance to Tambee’s project. Some poem titles call out in French or Danish, as in the pieces “i’m pluie,” “sacré,” and “wont dansk.” Letter combinations that appear cryptic to an anglophone reader may well have resonances in other tongues.

It’s natural to wonder how these poems might be performed aloud, and the curious few can view such a performance on the publisher’s YouTube channel. In the 2023 Gaudy Boy Poetry Prize Finalists Reading video, Tambee reads in a slow, deliberate manner, carefully slurring through ambiguous letter combinations, and repeating word stems as necessary to articulate all variations implied by the text. The feeling is dreamy and somewhat disturbing, evoking struggle and determination.

Eke’s accomplishment is in presenting an unusual form to express the psychological phenomenon of multivalent comprehension. The content of each piece is almost incidental, and indeed many of the poems come apart into phrases that individually are rather banal. The vocabulary is abstract, with few sensory details or even a lot of concrete nouns. It’s interesting to notice resonances between words like “clever, cleaver, lever, leaver, level, culpable” but it’s also a bit like reading the dictionary for fun. The paradox of this book is that it implicitly deals with embodiment (stuttering, hesitation in the mouth) but contains very little of explicitly embodied experience. There’s a protective layer of distance to the work that keeps potential overwhelm in check. Danger looms, but stays at an intellectual level where we, readers and writers, can enjoy the thrill of possibility without risk of loss too great to keep under control.

Eke, by Wahidah Tambee. New York, New York: Gaudy Boy, LLC; July 2025. 106 pages. $16.00, paper.

Dawn Macdonald lives in Whitehorse, Yukon, where she grew up without electricity or running water. She won the 2025 Canadian First Book Prize for her poetry collection Northerny (University of Alberta Press).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.