Introduction: Necromodernism and the City of the Dead

Necromodernism names the condition of literature after the death of its modernist and postmodernist projects. If modernism imagined the text as a monument to cultural renewal, and postmodernism played among its ruins with irony and bricolage, necromodernism arises when both gestures have collapsed. Literature no longer renews or even parodies, but persists parasitically, feeding off its own cadaver. Its temporality is recursive: the future is accessible only through the remains of the past, the archive reconfigured as necropolis.

Louis Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy—comprising The Combinations (2016), Death Mask Sutra (2018), Vampyr (2020), Glitchhead (2021), and A Tomb in H-Section (2025)—offers perhaps the most sustained necromodernist architecture in contemporary writing. Across these books, Armand constructs an enormous city-text, an archive of ruins that feeds endlessly on its own detritus. These novels are less stories than mechanisms of recursion: sites where language decomposes, mutates, and survives by consuming itself.

What follows is a traversal of each text in turn, mapping how the Golemgrad Pentalogy stages necromodernism: from unreadable excess and funerary sutras, through vampiric montage and glitch seizures, to the final tomb of language itself.

The Combinations: A Casino Archive

The Combinations stands as the monumental opening of Armand’s project, an almost-thousand-page megatext sprawling across the city of Prague, spawning centuries of its troubled past(s) and problematic present(s). As the publisher’s blurb puts it, Prague in this book appears as

Golem City, the ship of fools boarded by the famed D’s (e.g. John) and K’s (e.g. Edward) of the 16th/17th centuries (who attempted and failed to turn lead into gold), and the infamous H’s (e.g. Adolf, e.g. Reinhard) of the 20th (who attempted and succeeded in turning flesh into soap). Armand’s prose weaves together the City’s thousand-and-one fascinating tales with a deeply personal account of one lost soul set adrift amid the early-90s’ awakening from the nightmare that was the previous half-century of communist Mitteleuropa.

Armand’s Prague becomes a ruinous city-text, where language is an accumulation of pastiche and citation, the detritus of literary history endlessly recombined. The city itself features as archive—e.g. its (in)famous Marian Column on Old Town Square is portrayed thusly: “an anachronism, a relic from the past,” lying the middle of Golem City, is portrayed here as time-disciplining device: “her noontide shade decreed to mark … the Golem City Meridian so-called, Mitteleuropa’s Greenwich Mean: all timepieces synchronise!”

The book’s very scale defies narrative coherence. Like Joyce’s Ulysses or Finnegans Wake, it insists on unreadability as a mode of survival. The text is less a novel than a casino, its labyrinthine corridors recursive loops, designed to exhaust us rather than to guide, its 64 chapters/rooms forming an endless labyrinth, each filled with citational detritus, digressions, and fragmentary narratives. Necromodernism is here staged as a refusal of closure, with culture surviving not through the promise of transcendence but by trapping itself in cycles of repetition. In necromodernist terms, The Combinations transforms the archive into a mausoleum. The novel is a vast storage chamber of quotations, fragments, dead forms. Yet, precisely in its unreadability, it persists. Its excess functions as a kind of entropy, a system whose purpose is its own exhaustion. We are drawn into a textual necropolis, a combinatory machine that devours itself while refusing to die. As Richard Makin’s blurb on the fourth edition of The Combinations puts it, “The spine of the novel is a reliquary of the past, urban wastage compacted in descending chronology, slowly sinking down to the immutable …”

Armand’s The Combinations unfolds as a vast necromodern machine whose primary operation is not narrative development but archival recursion, a novel that reads and re-reads the ruins of its own making. At the center of this circuitry stands Němec, the archivist-protagonist, whose consciousness is less a repository of memory than a programmed interface, a downloaded aggregate of other people’s recollections, fragments, and spectral data. Early in the novel Armand makes this clear in a passage that exposes the logic of the “mass archive,” where memory no longer belongs to the subject but to the System that stores and retrofits it:

But this isn’t a simulation, all the scenarios are real […] A pair of eyes above a green mask where nose & mouth should be—the face of God, apparently […] as if he’s being reprogrammed to wake up somewhere … with a creeping suspicion something’s on the other side watching him through the glass—confirmation, it might seem, that at least he’s someone else’s hallucination & not just his own … What if even his most private inklings, childhood memorias, secret humiliations, were just vestiges downloaded from the mass archive, nanospasms of a collective brainwave, retrofitted?

Here Armand crystallizes the necromodern temporality of his fiction: memory as retrofit, time as an endless process of technological overwriting. Němec’s “private inklings” turn out to be nothing more than public software—fragments of a distributed system of remembering whose source is long extinct. The human subject becomes the playback device of the mass archive, a terminal of residual data. Armand’s ellipses and recursive syntax enact this condition formally; the prose itself stutters, loops, and replicates, mirroring the system it describes.

Death, accordingly, becomes the novel’s organizing principle—not an ending but a process of reanimation. When the Professor dies “playing a one-sided game of chess in the bath,” the scene fuses pedagogy, science, and mortality in a single necro-epistemic image:

Within the regime of organised optimism that governs our modern medical institutions there prospers a demon of efficient irrationalism … It happened while he was playing a one-sided game of chess in the bath. The first picture that came into Němec’s head … was of the Prof dead in the water, like Marat … & a black knight lying just out of reach on the wet tiled floor … there was the letter & then there was the letter inside the letter, the one no-one could see because it was addressed only to the deadman.

The scene collapses the Enlightenment imagery of reason and order—the chessboard, the letter, the scientific experiment—into the watery theatre of decay. The image of “the letter inside the letter” literalizes the necromodern archive as a correspondence addressed to the dead, prefiguring Derrida’s postal logic of the spectral missive—a correspondence addressed only to the dead. Armand’s “black knight” signals the futility of the game: chess, as the novel’s recurring metaphor for thought, collapses into necro-pedagogy. The chessboard, that classical allegory of reason and order, is here submerged in the bathwater of dissolution; its pieces become funereal tokens. Armand converts the epistemic structures of Enlightenment rationality—medicine, pedagogy, communication—into mortuary devices. In this sense, knowledge is inseparable from its own autopsy: every act of inscription presupposes a reader who is already dead.

Such images of technological necromancy recur throughout the text. The novel’s settings—its libraries, offices, and laboratories—are built from bureaucratic materials, the infrastructure of information storage and state control. A typical interior setting description reads, “down another corridor lined with filing cabinets, to a glass partition door with PRIVATE written on it […] The office […] was cramped with half-a-dozen desks & bookshelves stuffed to overflowing.” This is the architecture of necromodernity: the archive as mausoleum, where data and death cohabit. Even the Professor’s study is described as “overladed shelves, books piled on the floor, filing cabinets & bundles of dusty manuscript,” with knowledge lying buried under its own accumulation; the archive not a repository of truth but a tomb of excess.

Armand’s historical consciousness is likewise archival and terminal. The novel’s evocation of Tomáš Masaryk’s fall from the Castle window (“An indifferent morning sometime in March. Year: 1948 […]. Official verdict: Suicide … picture an office in the Castle with filing cabinets & desk”) situates the Czech twentieth century as a bureaucratic tragedy, its political history reduced to paperwork. The death of Masaryk, like the death of the Prof, becomes another “letter inside the letter”: a secret addressed to no one, sealed within the institutional archive of the state.

As the book’s sequences spiral toward entropy, its imagery grows increasingly subterranean. The catacomb passage describes “concentric rings of spilt wine, candle stubs, bits of broken cutlery […] fragments, echoes […] coded messages relayed through the subterranean dark […] FACILIS DESCENSUS!” Here the novel literalizes its descent into the necropolis of history: meaning disintegrates into fragments and echoes, a Latin tag surviving like an ossified relic of the humanist past. What remains is code—not communication but signal, noise, and residue.

Near the end, Armand turns his archival poetics on itself. A section titled NOTES ON FAILURE catalogues its own collapse: “NOTES ON FAILURE 1–8 … 8 PROJECTS FOR AN OPEN-ENDED ETCETERA … LETTERS TO NON-ENTITIES … LETTERS TO FAMOUS PEOPLE (MOSTLY DEAD).” The self-referential inventory reads like the table of contents for a dead literature. The novel thus becomes an archive of its own impossibility—a structure that documents its own ruin. This movement toward exhaustion culminates in the ethics of survival. In Armand’s necromodern cosmos, survival is not resistance but submission, “the lowest form of passive resistance, like toilet training for the right-thinking mind.” To live on is merely to persist within the parameters of the System, to repeat its protocols in miniature. Survival is administrative habit—life as institutional afterlife.

Across its sprawling architecture, The Combinations constructs a vision of modernity as self-cannibalizing archive. Memory becomes data; death becomes procedure; survival becomes bureaucracy. The novel itself operates as an 888-page necropolis of information, a total system sustained only by the energy of its own decay. Its pages are both tomb and terminal—the humming afterlife of the archive where language continues long after life has stopped.

Death Mask Sutra: Plague Text and the Necro-Archive

If The Combinations maps necromodernism on the scale of the city, Death Mask Sutra (2018) turns to the body. Here, Armand stages literature as funerary practice: the text is a death mask, a relic of the corpse, a ritual inscription of what has already decomposed. The sutra—with its repetitive, mantra-like form—mirrors this process: language repeating itself endlessly, less to communicate than to persist.

The necromodernist imagination here is deeply material. The mask does not preserve life but reproduces its deathly trace. Writing becomes a plaster cast, fixed to the absent body beneath. Sutra is repetition without transcendence, mantra without promise. Each phrase is residue, an echo of what cannot return. This necro-archival practice is not mournful but insistent. Death Mask Sutra insists that literature has no choice but to inscribe absence. It turns language into cadaver, text into relic. If modernism sought renewal and postmodernism delighted in play, necromodernism accepts only necrosis. Armand’s sutra does not celebrate recycling but endures within the very matter of decomposition.

Death Mask Sutra continues the necromodernist architecture inaugurated by The Combinations, but shifts the register from labyrinthine fiction to scriptural liturgy. The book’s structure—its partition into three main sections, Caveat Scriptor, Caveat Lector, and Post-Scriptum, each further subdivided into brief, usually single-paragraph subsections headlined e.g. “First Thesis,” “The Denizens of History,” “Anti-Summit,” “10 Days of Solitude,” or “Walt-Geist”—mimics the arrangement of sutras, commandments, or revolutionary theses. Yet Armand’s “sutra” is not revelation but recursion: a scripture of exhaustion in which writing becomes the carrier of contagion. The text is both archive and epidemic, each sentence a vector through which thought transmits its own decay.

In the opening section, Caveat Scriptor, the act of inscription itself is rendered pathogenic: “Now the Doomsday Book opens, but I can’t read it. / Someone’ll have to bloody the pages first. Going round on black squares. / […] Infects whoever tries to make sense of it.” The “Doomsday Book,” that archetype of bureaucratic totality, here becomes unreadable, its knowledge legible only through contamination. The book that records all becomes the book that no one can open without infection. Armand literalizes the metaphor of the plague text: meaning is produced only through contact, through the violence of touch. The black squares evoke both the chessboard and the printer’s block; language and mortality become moves in the same terminal game.

The following section, Caveat Lector, transfers this contagion from the scriptor to the reader:

VIEWER WARNING

For the next 90 minutes, you will be exposed to visually traumatic images & yr ears will vibrate w/ horrible audio sensation! If you suffer from heart problems, ego conflicts, or do not possess an active imagination, then this programme is not for you! You have mere seconds to grab yr remote control & change the channel or turn off yr TV before this show begins!

The mock-broadcast voice assumes that the work is a transmissible substance, something we will be exposed to. The language of contagion anticipates the “plague” motif of later sections. Reading or viewing becomes a form of contamination—a process that implicates both medium and spectator. Death Mask Sutra thus begins as its own “epidemiological event,” warning us even as it infects us.

The plague ceases to be metaphor and becomes the fundamental mechanism of society itself: “All forms of the Plague today are, in the final analysis, based on the generalised & stable divisions of class society, between those who give orders & those who carry them out.” The contagion is no longer medical or moral—it is structural. The necromodern world is one in which plague is the organizational logic of bureaucracy, the virus institutionalized as governance. Here Armand’s sutra functions as political anatomy: an x-ray of social death. Infection is hierarchy; the pathology is order. From this diagnostic plateau, the mid-book turns toward choreography and spectacle.

In “Ministry of Economic Terror,” the city becomes a theatre of cordons, lenses, and PR: “Officials made TV faces at the cameras, talking about renewed economic growth […] A huge banner unfurled in the firelight: MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC TERROR.” The section “WALT-GEIST” detonates the sutra’s salvage poetics into a single imperative—“IT’S FOR US … TO BUILD RUINS AMONG THE ASHES!”—while an immense projection of “Papa Walt” burns on the Tower: “a ritual sacrifice accomplished by means of grossly distorted pixels.” The aphoristic hammer-stroke that follows (“It wasn’t a flash of lightning from the blue, but a sky full of smoke & ashes”) turns eschatology into infrastructure: not revelation, but particulates; not the bolt, but the burn.

Read as a whole, the sutra’s movement is exact: from contagion of reading to political staging and media liturgy to containment as lived composition. The early injunction “Teleology = History’s ghost. Voices like flies beneath dead halogen” is realized mid-book as a governance of images, and late-book as the pared-down metrics of keeping breath, food, and footage inside a sealed room. What emerges is necromodern scripture: not a doctrine to be believed, but a rite to be endured—compiled from code stubs and theses, broadcast warnings and riot vistas, white-crossed doorways and basement reels. Or as the book’s own structure intimates: the “plague” is the medium; history is its residue; reading is the ritual that keeps the system humming.

Vampyr: Recursion and Contagion

With Vampyr, Armand shifts from archive to parasite. The vampyr is not a figure of eternal life but of endless recursion: a being that survives only by consuming the living, endlessly replaying its own clichés. In necromodernist terms, the vampyr is the embodiment of literature itself, surviving only by feeding on its own detritus. Early on in the text, we read: “Originally, all of the dead were Vampyrs. Yet we do not come from the past, but from the future.” The temporality is clear: vampyric existence is recursive, looping backwards and forwards at once. It is not progress but repetition, survival by feeding on remains: “The vampyr exists only as a rhetorical category at odds w/ an ontology that situates it within an organic continuum.” In other words, vampyr is not an organism but a language-game, a category of discourse. Literature is vampiric because it cannot transcend its own citationality; it exists only in the parasitic relation to past texts.

Armand stages vampyrism not just thematically but formally. Vampyr is a montage of fragments, citations, grotesque juxtapositions. Its textual practice is vampiric, feeding on exhausted tropes, clichés, the debris of popular culture and theory alike. Its contagion is linguistic: “The contagion has passed beyond the mere increase of an illness & become the illness. Its vector is that of History itself.” Here language itself is epidemic, history itself a plague. Necromodernism is less a diagnosis than a pathology: literature survives as infection, proliferating uncontrollably, unable to be contained.

Vampyr is both culmination and auto-deconstruction of Armand’s oeuvre. Its vampirism is not only thematic but structural and autobiographical: the novel consumes its author’s prior forms and motifs, metabolizing a decade’s worth of textual experimentation into a terminal spectacle of entropy and reanimation. In necromodernist terms, Vampyr stands as Armand’s self-exhumation—a textual revenant feeding on its own remains. It no longer builds new architecture (as The Combinations did) but scavenges ruins; it no longer theorizes apocalypse but performs it linguistically. The book’s genius lies precisely in this act of self-devouring: Armand’s corpus turns upon itself, transforming creative exhaustion into productive decay. Vampyr is not a new beginning but an undead continuation—a digest of the end, which is also visible from its central rewriting and rewiring of the COVID-19 pandemic, under whose conditions it took shape.

As is evident in the “@RealPresidentChloroqueen” motif, which epitomizes Vampyr’s necromodernist strategy of collapsing the spectacle of the present into the language of its own decomposition: “@RealPresidentChloroqueen: Vamps are hot, huge ratings! Crows not so much.” Ostensibly a parody of the Trump-era Twitter handle, it fuses sovereign authority, populist spectacle, and medical disinformation into a single necrotic signifier. The handle’s mutation of “Trump” into “Chloroqueen” (combining chloroquine with the monarchic “queen”) encapsulates Armand’s vision of power as viral parody: the ruler as algorithmic echo, the head of state as meme. The necromodernism here lies precisely in this logic of reanimation—the way language, drained of referential life, continues to circulate as undead code. Vampyr’s @RealPresidentChloroqueen tweets from the twilight zone of dead media, where political discourse has outlived politics itself, and where the machinery of communication sustains only the memory of meaning. In Armand’s world, the presidency becomes a “mass archive” of contagion, the body politic a zombified feed, endlessly refreshing its own entropy. The necromodern subject here is not the tyrant or the follower but the system itself: an automated necropolis of slogans, reproducing sovereignty as performance after sovereignty has died.

Glitchhead: Convulsions of the Interface

If Vampyr is parasite, Glitchhead is seizure. Here necromodernism is figured through technological collapse: feeds corrupted, language convulsing, narrative reduced to glitch. Writing becomes error-message, download artefact, corrupted file.

Glitchhead refuses coherence. Its pages are aphorisms, fragments, memes, seizure-texts. It is an archive of convulsion, a stuttering feed that never resolves. In necromodernist terms, glitch is not failure but condition. As Vampyr, its companion piece, had posited, “The end of writing is the end of history.” Yet, adds Glitchhead, this end does not arrive; it repeats, seizes, convulses. Writing does not transcend glitch but inhabits it. This is necromodern survival: persistence through breakdown. Glitchhead insists that the glitch is not interruption but mode of existence. Literature survives not by overcoming collapse but by repeating it. If modernism sought totality and postmodernism played in fragments, necromodernism lives in seizure, convulsion, noise.

What makes Glitchhead necromodern is precisely its refusal of transcendence. The glitch is not a failure to be overcome; it is the mode of survival itself. Literature continues not in spite of its breakdowns but through them. In its necro-lyric coda across pp. 604–611, language literally collapses into epitaph, its fragments turning grave-markers of their own exhaustion: “only underground do you know / where you truly stand … THE MOMENT YOU THINK Y’RE REAL, / YOU LET YR GUARD DOWN,” and immediately after: “no image but mimesis itself is the re present ation of power … who shall be the subject of these further investigations? FINIS CORONA OPUS,” followed by the final dissolution: “i am the rain. i am the image in the kaleidoscope looking out. i am the creeping anxiety. i am what makes sense of life after you are dead .… i am the insomnia of the world. i eat what i create. i am beautiful.”

These three strata enact the book’s terminal logic of descent followed by collapse followed by dissolution. The “underground” is no longer metaphorical, it is the sub-lingual chamber where signification is buried; self-recognition (“you think you’re real”) triggers annihilation. The text then turns autopsic, dissecting its own apparatus: representation = power = mimesis = death. And the “i am” litany on pp. 609 functions as a reverse-Genesis: creation speaking itself into erasure. In effect, Glitchhead’s ending reconfigures apocalypse as feedback loop: language eating itself, poetry becoming its own necrotic residue. The final cadence, “the terrible beauty of THE END,” seals the book’s program: to push representation past endurance until only the glitch—the seizure of signification—remains vibrating on the page.

A Tomb in H-Section: The Necropolis of Language

The cycle concludes with A Tomb in H-Section, a novel that literalizes necromodernism as tomb. Here the text itself is mausoleum, a necropolis of language where residues are catalogued, fragments stored, ruins preserved:

—Poor Lost Souls going straight back to GO, downriver to the Big Water […]. All Lost Souls get sent up to Mouldyheaven for tabulation & reassignment by a queensize Hollerith machine, then put on the next available transport straight up to Kafka Central. Or down, depending on yr POV.

Bureaucracy here is reimagined as necropolis, an archive of the dead filed and reassigned by spectral machinery. Golemgrad itself is ruin, detachable fragment, processing plant where detritus is re-coded as accountancy:

Bet you didn’t know there’s a detachable piece of Ol’ Golemgrad smackbang in Hamburg Bay, or, ipso facto, what’s left of it, w/ the cranes & shipping containers & bomb craters & all that? … Seeing as that’s where the Processing Plant is. G.O.D. in his countinghouse, etc., keeping the ledgers in good order.

The grotesque and spectral populate this necropolis, figures of collapse and parody.

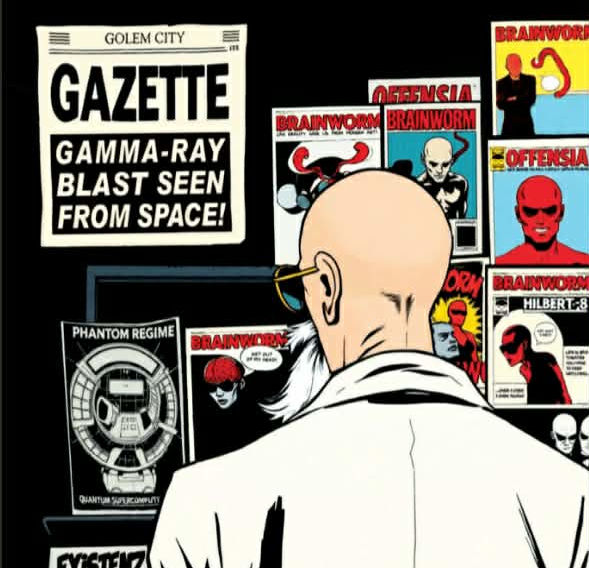

What is decidedly new are the visual strata of A Tomb in H-Section, as integral to its necromodernist structure as the text itself. The novel’s comic-book panels, collaged advertisements, and pseudo-archival graphics do not merely illustrate the narrative; they perform its decomposition. Across the book, Armand treats the visual page as a palimpsest of expired media: the halftone dots, distressed speech-balloons, and mismatched typography echo the decaying surfaces of pulp printing, Cold-War propaganda, and post-industrial signage.

These aren’t nostalgic quotations but archaeological finds—each panel a fossil of a communication system long dead. In necromodernist terms, the comics function as after-images of culture, where the aesthetics of mass reproduction survive only as ruin. Panels are often overexposed or misregistered, evoking the same “sunspots on overexposed Kodachrome” that describe the dissolving bubble-people in the prose. We experience the visual field as a kind of morgue for imagery: captions detached from frames, frames from sequence, sequence from sense.

Many of these pages reproduce the look of mid-century EC horror or Cold-War noir, yet their colors are inverted, over-saturated, or digitally corrupted—visual equivalents of Armand’s necromodern language glitches. The grotesque hybrid figures (half-cartoon, half-cadaver) mirror the novel’s textual grotesques: the talking ratoid, the bureaucratic revenants, the film-crew haunting Elsinore. In both modalities, the human form has been replaced by its industrial surrogate. The result is not a return to pop but its exhumation: a comic-strip medium resuscitated as corpse. Formally, these images extend the novel’s critique of archive and spectacle. The comic sequences often appear as redacted documents or classified exhibits, complete with numbering, stamps, or perforated edges. They mimic the bureaucratic aesthetics of filing, surveillance, and evidence.

The fusion of word and image thus becomes the tomb itself. The novel’s design performs what its text describes: a necropolis of media, where print, comic, film, and data all coexist as residues of an exhausted civilization. To read A Tomb in H-Section is to wander through this museum of half-legible panels, overheard slogans, and decomposing color plates—a work of art that has already buried itself, yet continues, mechanically, to print its own epitaph.

Midway through the text, the necropolis expands from river and archive into a planetary ruin: “Exterior: day. Elsinore in the epoch of Gaza, stripsearched, bombed into oblivion, a gifthorse by any other name wld still etc.” The afterworld is geopolitical; Hamlet’s Denmark and modern Gaza share a single devastated syntax: “Ah all the untellable tragedies. No such thing as an innocent child. Bile falls from the sky onto their heads. Elsinore a pile of rubble. ‘My heart is a pile of rubble’.” History here is waste management, its tragedies converted into rubble and bile. The media specter replaces witness: “The artist formerly known as ‘Hamlet’ slouches down the corridors of Elsinore followed by a documentary film crew. He eats an apple, talks to an old pederast’s skull, can’t tell the difference between the two.” The world records its ghosts in endless replay. Later, “Jr’s chatbot is called Yorick whose real name was Artemidorus of Daldis.” The gravedigger becomes an algorithm; speech itself a digital séance: “Talk’s cheap but still a hanging offence wrong words in wrong order. Produce No Evil, Distribute No Evil, Sell No Evil.” Language, criminalized, and commodified, ends as the final corpse.

For A Tomb in H-Section, literature persists only as archaeology, as excavation of its own ruins. If The Combinations was an archive casino, Death Mask Sutra a funerary relic, Vampyr a textual contagion, and Glitchhead a textual glitch, A Tomb in H-Section is literary necropolis. The Golemgrad project ends not with transcendence but with catalogue, not with renewal but with an archive of failure, a terminal scripture where even tragedy decomposes into ledger, and the last living word is filed, indexed, and entombed.

Conclusion: Necromodernist Architectures

Across its five volumes, Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy maps the architectures of necromodernism. The Combinations presents unreadability as survival, casino-text as mausoleum. Death Mask Sutra inscribes the body as necro-archive, sutra as mantra of decomposition. Vampyr stages literature as parasite and contagion, surviving only by feeding on remains. Glitchhead enacts seizure, glitch as survival condition. Finally, A Tomb in H-Section catalogues ruins, narrative as necropolis. Taken together, these works demonstrate that necromodernism is not so much a movement as a contagion, not so much a style as a condition of writing. In Armand’s writing, literature persists only by metabolizing its own cadaver, surviving in ruins, endlessly looping through its own exhaustion, and his Golemgrad stands as necromodernism’s most monumental instantiation: a city of the dead, built from the ruins of literature, where writing persists not despite collapse but through it.

David Vichnar teaches at Charles University Prague. He is also active as an editor, publisher, and translator. Apart from numerous edited volumes, his publications include Joyce Against Theory (2010), Subtexts: Essays on Fiction (2015), and most recently, The Avant-Postman: Experiment in Anglophone and Francophone Fiction in the Wake of James Joyce (2023). He translates from/into English: his book-length translations include Philippe Sollers’ H (from French) and Melchior Vischer’s Second through Brain (from German), as well as Louis Armand’s Snídaně o půlnoci (English-Czech). He directs Prague Microfestival and manages Litteraria Pragensia Books and Equus Press. His articles on contemporary experimental writers as well as translations of contemporary poetry and fiction—Czech, German, French, and Anglophone—have appeared in numerous journals and magazines.

Image: Equus Press, A Tomb in H-Section by Louis Armand, pp. 11

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.