Here we go again! Putting together this year brings me such joy and I hope you find something beautiful here, too. Sometimes, it can seem as if no one reads anymore but making this list reassures me that there are a lot of us out there, still trying to learn, still trying to create, still trying to connect. Unburden yourself from the disappointments of the past year by getting lost in these words and supporting indie lit. Reading is resistance! We’re still here. Like my sister and I used to say, I raise an imaginary glass to you now and clink, “Cheers to the weirdos!” I’m glad we’re here together. —Jesi

The Equestrian Turtle and Other Poems

by César Moro, translated by Leslie Bary & Esteban Quispe

(Cardboard House Press)

“Your gaze of sea cucumber of whale of flint of rain of diaries of wet suicides / the eyes of your white coral branch gaze.” Opening with an epigraph from Baudelaire’s Journaux intimes (“The verdant darkness in the humid eves of spring”), Leslie Bary & Esteban Quispe’s dazzling translation of Peruvian surrealist poet César Moro’s The Equestrian Turtle is a geologically illustrious work of molten greens, pearlescent dreams, and hecatomb-love. With its anaphoric verve and diamond-sharp imagery, The Equestrian Turtle is not only a meditation on the convulsive beauty of the nonhuman world, but it’s also been described as a “book of psalms” dedicated to Moro’s eight-year romance with Mexican army officer Antonio Acosta. Also included in this first-time bilingual Spanish and English edition are poems Moro omitted from the original 1940 manuscript due to design limitations (“But you should grow me or dissolve me in hurricane winds / Like a fistful of free leaves / Into the free wind of love”). The deliciously incendiary experience of reading Moro’s The Equestrian Turtle reminded me of the first time I read Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell. These are shadow-dwelling surrealist love poems radiating a “diamond insanity” unlike anything I’ve read before.

Our Human Shores

by Josh Fomon

(Black Ocean)

“The deafening roar / of fire, a giant / ocean of trees burning / like a sunset.” Taking inspiration from John Keats’ “Bright Star” sonnet, Josh Fomon’s second book of poetry confronts our geological epoch known as the Anthropocene. Like the concluding lines of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (“If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles”), Fomon, succumbing to a desire for totality, makes his poetic project one of transience and “human reclamation.” How do we–in our bodies and our minds–accept the truth of the Anthropocene and go on living? And loving? Fomon, as if trying to avoid ending (like any poet) writes his body, page after page, into excess (the 184-page book certainly diverges from the average 70-pager) as if his voice (“whippoorwill, down my throat, let it speed away”) could be erased by the elements at any second. Equating humankind’s “collective witness” to a “tree / stuck sideways,” Fomon continuously reaches in the direction of nonhuman infinitude (i.e. “exploding flower”) and away from the material limitations of the present. And, perhaps not so strangely, a Whitmanian eros is at play here, too. Fomon not only eroticizes the physical book-object (“Fondle this masterpiece / this new coastal glide”), but juxtaposes a language of reactive glands, organs, and orgasms with an anti-anthropomorphic language of kindling, tinder, and “cackled” ash. The poet leaves us humming alongside him—in some sublime imaginary between life and death. Unpredictable as earth itself, Our Human Shores is an immense and timely song of “new unending tide.”

The Book Is a Tower Always Never Watching

by Rachel Zavecz

(Cloak)

Panoptic, monstrous, and uncontrolled, this debut book is a tower is the shimmering black ooze of you (dot) reader smeared digital with interlocking language roaming—centipede-like—under a glossy tower of flattened red. With copyright page by glitching gyre, with possible future links to a silent chorus. A compilation of documents, an assemblage of meat. An introduction to poet Rachel Zavecz poet who always-never watches poet as tower and book as tower and tower as moth and moth as what hovers invisible over every numberless page of this book. Tower. Less. A page less number. Less a book than being in the wrong part of the animal, something lost inside the tower cries. This book is a tower crying a pearlescent glimmer of insect wings, a “mult.iplic.ation of num.bers”—always-never watching you, obedient reader. Pearl after pearl. A multiplication of moths. Don’t be fooled by the eyespots, obedient reader. Don’t be fooled by those kitten eyes. By those corneas of a “physician’s tender.” By the time you reach the book’s un-ending and its mysterious appendices, you’ll want to initiate a cycle reboot! This is a spectacular book of endless becomings! For fans of Hideaki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and E. Elias Merhige’s Begotten.

Bodies Found in Various Places

by Elvira Hernández, translated by Daniel Borzutzky & Alec Schumacher

(Cardboard House Press)

Praised by Cecilia Vicuña as a poetry that “restores the right of words to speak,” Bodies Found in Various Places is a truly captivating anthology of Chilean neo-avant-gardist Elvira Hernández’s collected works (1981-present day). While some might already be familiar with The Chilean Flag (2019), this corpus also presents the following volumes for the first time in English: Bodies Found in Various Places (2016); Giddy up, Halley! (1986); Corporal Punishment (2018); Santiago Waria (1992); and Birds From My Window (2018). Across these six works—and across time and space—Hernández’s uncompromising poetic voice navigates the longstanding effects and dehumanizing forces brought on by Augusto Pinochet’s authoritarian military dictatorship. Crucial in its investigation of consumerism (“How utopian and crippled, the eternal workers / The peaceful wounded grass, how many? / They drank the lead floating in the sweetest air”), state-sponsored violence (whose party could it be? / muddled nose-bleeds / gorged on arcades of demolished architecture”), shattered economies (“the bulldozers rise at dawn / the city rises and collapses and rises and / collapses rises and collapses rises”), and ecological destruction (“Nothing remains of the dragonflies”), the visionary poetry of Elvira Hernández remains essential reading for these devastating times. As Daniel Borzutzky & Alec Schumacher declare in their translators’ note, when it comes to new “apocalypses of dictatorship,” artists will turn to “new poetic and artistic forms.” Begin anew with Bodies Found in Various Places.

Defensible Space/if a crow—

by Ian U. Lockaby

(Omnidawn)

In “Pyromena: Fire’s Doing,” Anne F. Harris highlights the complexity of fire within a “poetic cosmology of Love and Strife” as explored in Empedocles’ On Nature. “[Fire] is a creative force with no boundary or limitation save its own reach,” Harris writes. “The fire of Empedocles is willful; it has phronesis (intent) and noma (thought).” Ian U. Lockaby’s Defensible Space/if a crow possesses a similar elemental will that simultaneously decenters the human (“outside of one’s reason / is another life”) while audibly revealing (“ev’ry / step a way”) the gradual coming-into-being of a human at odds with the Anthropocene (“All summer was / crows overhead, language / breaking apart in my hands”). Lockaby’s own landscape of love and strife is saturated with echoes of crow (“Black wings its way across your temperature”) and numerous manifestations of fire (“it’s snowing ash”; “carcinogen huff”; “fireweed fuse”; “horizon sizzling”; “homes in the logic / of arson”; “tire fire with / one eye”). Vital to Lockaby’s own poetic cosmology is an attention to the eternal “if” of sound. This poet makes a promise to his readers from the very beginning: “this book is / great—how it can make you / hear different / layers of it amplified in the stacked noise.” Promise kept. Every single line break not only surprises, but tangles you up in its “billowy echo of / crow voicings s s.” Deeply moving and intentional, Defensible Space/if a crow is an elemental event. A breathtaking book of heart for a burning world.

—Paul Cunningham, editor of Action Books

The Monroe Girls

by Antoine Volodine, translated by Alyson Waters

(archipelago books)

Likened to Thomas Pynchon but really Brian Evenson, Antoine Volodine builds post-apocalyptic worlds that are post-political, post-gender, post-humanistic, post-post. The opening chapters showcase his mastery of event, turning it beyond scrutiny. The translator deserves translator’s heaven. What a feat!

Miss Abracadabra

by Tom Ross

(Deep Vellum)

This dive into 1950s middle class New England via Virginia Woolf’s sentences and a Black woman’s spunky rebellion is charged, one long hot cable of revelation. Why weird? Ross can’t let go. The result is magical.

The Swan Book

by Alexis Wright

(Simon & Schuster)

OK, it’s not a small press but it is far weirder than a big press has a right to. The president of Australia is aboriginal and abducts a woman from the outback to be his wife, but discovers she is far more obsessed by black swans in the midst of the climate wars than with the world’s trappings. Sentence by sentence, a genre-defier.

—Terese Svoboda published her 24th book this year, second memoir, Hitler and My Mother-in-Law

Although I’m biased because I edited it for Hanging Loose Press—I need to recommend the first collection of Swahili Afro-Speculative fiction in English, The Witness of Nina Mvungi and Other Stories by Esther Karin Mngodo, translated from the Swahili by Jay Boss Rubin (December 1, 2025). This book was the winner of the Loose Translation Award, jointly sponsored by Hanging Loose Press and the MFA program in Creative Writing and Literary Translation of Queens College, CUNY. These stories move through spicy, varied, and always thought-provoking mental spaces. You may find yourself in speculative territory one moment, realism the next, dystopia often, but all the tales tell of relationships, politics, the everyday lives of Tanzanians—even if they also happen to have vampiric tendencies.

I also must not forget to recommend the ingenious City of Dancing Gargoyles by Tara Campbell published by Santa Fe Writer’s Project. Let’s put it this way: if you’re in the market for one-of-a-kind work of dystopian climate fiction, complete with garrulous gargoyles, gun-toting trees, and epistolary research, all wrapped up in a book that will cause you to reconceive of the climate of America and American letters, then this one’s for you.

—Caroline Hagood, author of Goblin Mode

Waling Waling Palpitations

by nawa angel a.h.

(First Matter Press)

This book undid me and put me back together again. The text itself is a permutative drag performance that does something to alter the DNA of your body. “i am what my mother hoped: something she could never know,” an echo of impossible possibility and matrilineal lineages.

The Dream of Every Cell

by Maricela Guerrero, translated by Robin Myers

(Cardboard House Press)

A good friend mailed me this book, and when I finally got around to opening it, I was immediately immersed. “I’m still searching for a river and a language flowing close and free: a vernacular language that will communicate and connect us to the vacant lot next door.” The title enacts itself, and I feel the dreaming of each cell in my body drawn to the language of these rivers, wolves, creatures, flows, becomings. A beautiful bilingual edition with the original Spanish poems alongside each translation.

The Time of the Novel

by Lara Mimosa Montes

(Wendy’s Subway)

This book is a strange and luscious exploration of the task of becoming a narrator, of entering fiction in a way that merges becoming in a familiar, human sense, and becoming in a mutable, cyclical sense, looking at the convergence of being and having an interior mind, with writing and narrating an interior mind. I absolutely loved this book.

Grandma’s Story

by Trinh T. Minh-Ha

(Silver Press)

This little text feels like a talisman that you want to carry around in your pocket, a haunted reflection on the transmission of story that is filled with enchantment, emotional intimacy, and the echoes of writers like Theresa Haky Kyung Cha and Leslie Marmon Silko, truly a portal into magic story realm.

For This and Other Cruelties

by Youna Kwak

(University of Iowa Press)

This collection somehow holds the contradictions, paradoxes, elemental distortions, attachments, miracles, and questions of mother-ness. Don Mee Choi’s blurb for the book states, “To be mother or not to be mother is what I kept questioning.” As someone who also often writes about mothers, mothering, mother-ness, this collection shook me and brought me into the profound depths of inheritance, relationship, and identity.

—Janice Lee, author of Imagine a Death and Separation Anxiety

Until It Feels Right

by Emily Costa

(Autofocus Books)

I’ve had this on my list to read since Autofocus published it a few years ago because I thought it sounded like a really raw and vulnerable collection of short essays—it did not disappoint. While I don’t have OCD, as someone with a panic disorder I related so much to the experiences of the author and found her journey through taking steps to make her life more peaceful and livable really moving. I’m reading her second book Girl on Girl right now, and it rules too.

Howling Women

by Shelby Hinte

(Leftover Books)

I’ve loved reading Hinte’s work online and I was lucky enough to pick this up at AWP a few weeks before it came out. Reading Howling Women felt like taking a literature or philosophy class by a wonderful professor who knows how to get you to really think about deep questions of right and wrong. It’s a searingly beautiful and heartbreaking book that spoke to themes of recovery from and response to horrible trauma, but did so through deeply memorable characters that you will care for in ways you don’t expect.

Log Off

by Kristen Felicetti

(Shabby Dollhouse)

I love this book about a young girl exploring the early internet because it made me remember so many things about being a teenager—how big and intense everything felt, how much art meant to me, how hard it was to not be understood by the adults in my life, and how wonderful it felt when I finally started to feel like I was understanding myself. The best part was that it didn’t make me feel sad or nostalgic about that time. Instead it made me remember the things that were important to me then—music, art, spending time with my friends—and how I can still fall in love with all of that now, in my 30s.

Blue Light Hours

by Bruna Dantas Lobato

(Grove Atlantic)

This novel, about the relationship between a daughter studying at a college in the US and a mother talking to her over Skype in Brazil is simple but deeply moving. I love this novel because it proves to me what I have always suspected: that a story can be about the quiet moments of change we experience in our lives and still be a page-turner. I loved these characters and I’m grateful I got to spend time with them; if, like me, you’ve had a loud and difficult year, this gentle book might be the medicine you need.

—Franco Romero, author of short works of fiction and nonfiction in Words & Sports Quarterly, Autofocus, and other publications

The Waves

by Virginia Woolf

(Oxford University Press)

This is perhaps Woolf’s most challenging and formally daring book, utterly unlike anything else she wrote, and singular even within the modernist canon. I found it to be one of the most moving portrayals of friendship, of its necessity and its difficulty. The six characters—Bernard, Louis, Neville, Susan, Rhoda, and Jinny—each alternates between a sense of connectedness with others and feelings of estrangement. This tension between isolation and community is arguably something that Woolf grappled with throughout her life. The Waves is written in poetic, flowing prose where one character’s voice melts imperceptibly into another character’s, presenting a series of monologues; the narrative at times resembles an undulating series of waves that washes over the reader. Elliptical and mesmerizing, The Waves is sheer brilliance and Virginia Woolf at her best.

Mr. Palomar

by Italo Calvino, translated by William Weaver

(Mariner Books Classics)

One of my personal favorites from Calvino’s oeuvre, Mr. Palomar addresses the act of looking, and it is as formally inventive as his more famous work, Invisible Cities. Eschewing plot and conventional character development, Calvino presents a series of vignettes in which the titular character, Mr. Palomar, looks at a specific subject—the sunset, a gecko, a cheese shop—and the looking leads to reflections on existence. Thus an encounter with touristic crowds in a Zen garden in Kyoto leads to reflections on the relationship between humankind and nature, and observations on an albino gorilla yields thoughts on the importance of objects and signs in human life. In some ways, this remarkable novel is the culmination of Calvino’s lifelong project of engaging with the visual and the nature of vision.

The Planets

by Sergio Chejfec, translated by Heather Cleary

(Open Letter)

A novel about friendship, grief, and the slipperiness of memory, The Planets traces the narrator’s recollections of his friend, M, who was abducted in Buenos Aires during an era of political turmoil. Reminiscent of Sebald’s novels, The Planets is layered and digressive, with tangents that take the form of the narrator’s ruminations or stories written by M. The meandering quality of the prose mirrors the many walks that the narrator took with M. throughout Buenos Aires during the years of their friendship. The Planets is also a novel about a city, and the way that the narrator’s memories are entangled with urban geography remains, for me, one of the most striking aspects of this remarkable novel.

Self-Portrait in the Studio

by Giorgio Agamben, translated by Kevin Attell

(Seagull Books)

This is a book of astute philosophical insight and elegant prose that presents a self-portrait of the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, while simultaneously going beyond autobiography. Through the images and objects in his studio—described as a space of potentiality—Agamben guides the reader on a walk through philosophy, literature, and art, weaving in personal anecdotes and snippets of philosophical discourse. Self-Portrait in the Studio is a meditation on the life of the mind, on the formation of ideas, and the friendships and conversations that are indispensable to that formation. The written text is interspersed with arresting images—photographs of friends, of Agamben’s studio, facsimiles of postcards and notebooks—rendering the book a sheer pleasure to read and re-read.

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now

Edited by Pauline Vermare & Lesley V. Martin; with Takeuchi Mariko, Carrie Cushman, and Kelly Midori McCormick

(Aperture)

Described as “a critical and celebratory counternarrative to what we know of Japanese photography today,” this groundbreaking book introduces the works of key Japanese women photographers, thus presenting a counterpoint to the current discourse on photography, in which male photographers dominate. Consisting of essays and artists’ portfolios, this book is an exquisite object with beautifully reproduced photographs and carefully researched essays that detail the challenges faced by the women photographers throughout their careers. Some of the most striking photos, which I had never encountered before, continue to linger in my mind. A fascinating read for anyone interested in photography or Japanese culture, or feminist revisions of art history.

—Christine Lai, author of Landscapes

The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat

by Brannavan Gnanalingam

(Lawrence & Gibson)

Writing within a hair’s breadth of the “real” current political moment in Aotearoa/”New Zealand,” Gnanalingam gives uncensored voice to Kartik Popat—wet-dream of the political white right—a member of the model minority who hates other immigrants. Popat half-arses up to levels of power that offer him opportunities for fame and grift giving fictional life to the new New Zealand politician—selfish, ignorant and incredibly dangerous. In Gnanalingam’s hands this novel is heartbreaking and hilarious, a call to action and a reassurance in an age of misinformation that what we are seeing is what we are seeing.

Lucy’s

by Always Becominging

In the country of my favourite poets, Always Becominging is probably my favourite poet. Lucy’s is a zine created for Wellington Zinefest at the end of 2024—it is probably impossible to find now but this can’t stop me putting it on this list. This collection of “loosies” understands that crying doesn’t always come from sorrow or laughter from happiness. Lucy’s cries in ecstasy and laughs in the abject sadness of our hardest things. Seek our Always Becominging’s work however you can—I promise you won’t regret it.

Kitten

by Olive Nuttel

(Te Herenga Waka University Press)

Dedicated “for the girls” Kitten is one of the most exciting novels to come out of Aotearoa in the last decade. Nuttel’s prose is crisp and direct and her control of narrative makes this novel incredibly compelling. Kitten’s narrator Rosemary walks us through the young and horny life of a big city then takes us on the journey home to small town Aotearoa. One of the few books I’ve read that explores so skillfully a sexuality big enough to recognise and hold trauma and grief.

Symphony of Queer Errands

by Rachel O’Neil

(Tender Press)

Everyone in Aotearoa with a heart is exhausted and angry at the moment and Symphony of Queer Errands is a collection of poetry that takes this rage and heartbreak and redirects it into music, play and humour. This is one of the books published recently that aims to imagine a new language for the problem of living through these times. O’Neil’s work hums with joy—a symphony of imagined instruments, non-lexical poems, love, lust, a guffaw at the unfunny ones who aim to crush us.

ScatterGun: After the Death of Rūaumoko

by Ana Chaya Scotney

(5ever Books)

ScatterGun: After the Death of Rūaumoko is a solo interdisciplinary performance work developed, written and performed by Ana Chaya Scotney that through its many forms explores grief, joy and the connection of the human body with its land. This version of the work captures the play for the page and in doing so expands what the space of the page—reinventing what a book is and what it can do. Like the book iteration of Nathan Joe’s Scenes from a Yellow Peril before it, ScatterGun: After the Death of Rūaumoko reimagines a magnificent work after its event and shares it with a whole new audience.

—Pip Adam, author of Audition

The Book of Delights

by Ross Gay

(Algonquin Books)

I’m very late to this book, but it landed at the right time for me. Gay’s lyrical essays, written daily over the course of a year, are a powerful reminder to leave room for the capacity for joy even as we consider the difficulty and brokenness of the world. Besides the titular delights that Gay frames for us, some of the joy here is the author’s ebullient prose and his impressive eye for details that would otherwise go overlooked.

The Association of Small Bombs

by Karan Mahajan

(Penguin Random House)

This 2016 novel should be required reading for political pundits of all stripes. The plot follows a cast of well-drawn, complicated characters affected by or involved in the bombing of a Delhi market, which irrevocably changes the course of life for all concerned. Through his depiction of the market bombing and its aftermath, Mahajan explores the complicated realities of political radicalization and challenges commonplace thinking about the roots of political violence.

Glass Jaw

by Raisa Tolchinsky

(Persea Books)

This debut collection of poetry does not read like a first book. Glass Jaw charts Tolchinsky’s experience as an amateur boxer, giving us an intimate view of both the boxing gym and of New York as it existed when she was training. These expertly crafted lyric poems wrestle with the weight of being human in both body and soul. Set in the gym, the boxing ring, and the urban environment, Tolchinsky’s work gives window into the ravaging complexity of identity, how we are multiplicitious, and how the different sides of us war against one another.

The Nickel Boys

by Colson Whitehead

(Penguin Random House)

This tightly plotted book is an instruction manual on building the emotional resonance and narrative surprise at the heart of enduring literary fiction. In the novel, Whitehead confronts how the twin specters of systemic racism and racist violence echo forward into our present, but he also leaves room for the possibility of redemption. The genius of narrative form here matches the wrenching intensity of content that won’t let readers look away, that requires us to contend with the weight of the American past, its stark injustices and its extraordinary sacrifices.

—Iain Haley Pollock, author of All the Possible Bodies

Bound

by Jubi Arriola-Headley

(Persea Books)

Jubi Arriola-Headley’s poetry had a profound impact on both my writing, as well as Steven Dunn’s, and we looked to his work as influence and guide when we were writing Tannery Bay. How devastating for us all to have lost Jubi in October 2025. In the past month I have returned to Bound to remember how Jubi taught us about Black, queer play, love, yearning, tenderness, and vulnerability. Thank you, Jubi. We love you, and you are deeply missed.

The Indelible Rememory of Marrow & Salt

by Bre’Anna Sade’ Bivens

(Ethel Press)

A moving, hybrid/multi-genre chapbook-portrait about family, memory, and the narratives we build, try to make sense of, and, ultimately, attempt to reconcile and shed is one of my favorites of the year.

Brillo

by Paul Cunningham

(Lavendar Ink/Dialogos)

A reimagining of Andy Warhol and Paul Thek’s takes on Brillo, a poetry collection that annihilates what one understands about the queer ekphrastic, the influenced, the inspired by. It is so deliciously unmooring and will shake you in the best possible way.

Timber & Lụa

by Lily Hoàng & Vi Khi Nào

(Red Hen Press)

I am so happy this book is finally out! Ten experimental “self-translated” short stories written in three different languages: Vietlish, Vietnamese, and English, a genius collaboration by two of the most exciting experimental fiction writers working right now.

—Katie Jean Shinkle, author of Tannery Bay and None of This Is an Invitation

The Vitals

by Marie de Quatrebarbes, translated by Aiden Farrell

(World Poetry)

The Vitals infiltrates a world of tenuous abrasions and slight jolts quietly holding at bay a torrent that, one senses, will crush the speaker (and us too). The veinous reigns over sensation. Arranged as a journal organized by months, Quatrebarbessustains emotional precision by spinning around the emptiness that assaults grief; it makes what hurts glow and bleep in its beckoning. The empty force of a wheel relays these poems’ lyricism: “For us, who are nothing but a blessed moment of life.” New to de Quatrebarbes’s poems, beautifully translated by Aiden Farrell, I’m taken by the perfection and lyric acuity of the writing:

Childhood lived in the bathrooms of a house smaller than most houses. On the tapestry shapes recited dictionary entries I took for images. If I think of the tears that follow the breaks and crashes: how to know when it’s one’s turn to cry? Surely the last breath meant she was resolute as no other exit connected with the room. On seeing her I said to myself: her eye is of gold and her mouth a secret.

It’s a book of vital motions and flowing variations on sorrow.

On Certainty

by Ludwig Wittgenstein, edited and translated by G.E.M. Anscombe & G.H. Wright

(Harper Perennial)

In the last year and a half prior to his death, Ludwig Wittgenstein recorded his thoughts on certainty and doubt in response to Thomas Moore’s writings “Proof of the External World” and “In Defense of Common Sense.” What can we say we know for sure? Wittgenstein’s reflections stressed how certainties are grounded in assumptions and beliefs that we do not question for they are simply widely accepted. These beliefs govern our ability to make assumptions and statements about reality. Certainty exists in a context, a network of relationships, “a form of life” from which the language-game of certainty emerges: “What we believe depends on what we learn,” and “the questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions exempt from doubt are as it were like hinges on which those turn.” There is a point beyond which I cannot offer more reasons to support the certainty that I am named, Isabel, or that I have always lived on planet earth, that is, a point beyond which certainty becomes persuasion and belief. The weird world of doubt is unnervingly present these days when the triumph of blatant falsehoods has taken hold. Reading On Certainty offers both a purifying ritual for the mind and a tool for diagnosing the present.

Wave of Blood

by Ariana Reines

(Divided)

Ariana Reines’s Wave of Blood—a book of poems, essayistic interludes, confessional pauses, and many analytic insights—is an essential work of reckonings and fierce self-examination. By offering a model for self-study, it is also a manual of sorts in the manner of Thomas à Kempis or Teresa of Ávila—the writer’s introspection is arduous, admirable. Reines searches for a mode of being that withstands the pressure and devastation of a deadly present. Her words face atrocity, historical and familial trauma, unearthing questions that link us all as she responds to the enfolding crisis in Gaza. How to speak of it? The bookwitnesses the failure of words and records gaps between lines. So many of the one-line stanzas feel persecuted by a collectively driven silence because of the white around them:

How is it so

Many bodies have sunk

Into the earth

So quietly

These billions of years

How did we never feel it?

Or did we? All that feeling

They keep telling you is nothing.

With Milton in mind, Reines considers our technocratic, computerized society, one that makes violence more effective, operational, and inescapable. Yet Reines’s book places flight aside and allows the reader to roam in the present disappearance of, well, so much.

—Isabel Sobral Campos, author of The Optogram of the Mind is a Carnation

This Little Art

by Kate Briggs

(Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Pink Waves

by Sawako Nakayasu

(Omnidawn)

These two books, along with a much lauded and institutionally celebrated book that I need not plug here, were new to me or were part of my re-reading (always newness can be found, I have found), to prepare for class & to be a human who enjoys thinking without destination & to contemplate something Suzanne Scanlon wrote about in January of 2025: Joseph “Brodsky’s admonition that the only true subjects are Time and Language” …

And although the intersections of ideas were coincidental, they were delicious and radical. I want(ed) to add to Scanlon’s summary: “and Reading.”

The only true subjects are Time and Language and Reading.

Sawako Nakayasu’s Pink Waves ekphrasticizes Waveform by Amber DiPietra & Denise Leto and Adam Pendleton’s Black Dada manifesto, and in her centering of the performance of making poetry in response she thus also centers accident and chance and discovery: of cadence? as response? as a performance? Yes? Discovery of cadence while performing? Yes? Yes. So: time and language and reading are a wild tiny drop at the middle of the waves:

i think some people just never stop writing

Repetition is the form over which the waves of thinking break. The book is constantly ceding control. A text might be possessed by its own sources. These sources might be known and unknown. The only true subject is Reading. Or Language. Or Time.

Kate Briggs gets us there, too, with attention to Literature as a communal praxis that infects/affects the individual’s interiority.

The project of Literature is about shared labor.

She’s translating, sometimes, in the text. I mean: while writing this book and as the writing of this book, she’s translating. In particular, she’s translating Barthes’ lectures from right before he died.

Briggs is unconcerned about clear boundaries between: her sources, her translating, her reading, her writing/her “writing,” her gaze, her thinking, her speaking, her reading aloud to her children: it’s all communal and fluctuating, a performance of cadence and language that exposes the mind and the body to human history, like a big ear or a wound. We watch her reach for a pencil and dog-ear a page. While reading. Which is writing. While reading, which is translating. While reading. Time itself.

Briggs’ thinking about translation as conjoined with the way that reading some singular moment gives you a feeling—“What kind of feeling? Can’t you describe it more closely?”—leads to a sentence from Iris Murdoch:

“The coming day had thrust a long arm into the night.”

So here is the dawn, I remember thinking to myself, as I marked down the page. Here is the dawn in a sentence. Here is the dawn as I have never seen it before. But as I recognize it nonetheless (with the new knowledge that the line seems to be somehow inaugurating in me). Here is the dawn, as I now wish to have made it appear. Here is the dawn as I now might have wished to write it.

I’m too long-winded here and/but still desperately want to mention Jay Besemer’s The Horse, which made me think about reading and breath—“& the built world trembles with the strain of the long-held/ breath”—and, uncouth as it might be to namedrop one’s own partner, Philip Sorenson’s Meanwhile in Ephesus (published only in print and only for free, in Chicago, on Z-Axial Press) which articulates a mind-blowing relationship between “edging” and time and narrative/narration; and the cultural anthropology book The Senses Still by C. Nadia Seremetakis (University of Chicago Press), which allowed me to (digressively) think into what the smallest sensorial archive might “mean” for preservationist tendencies in writing: Language! Time! Reading! The only true subjects.

—Olivia Cronk, author of Gwenda, Rodney

Notes from Underground

by Orrin Grey

(Word Horde Press)

Creepy, crawly, and host to macabre beings, with the old school flair of a late-night stroll through the video store, Notes from Underground sits squarely in the upper echelons of world-building horror. This horror laureate’s Hollow Earth is not a static realm that awaits intrepid exploration but bubbles beneath our own in twisted ways that harken back to Clive Barker. The madcap backdrop of the text feels Dead & Buried in the best way.

The Endless Week

by Laura Vazquez, translated by Alex Niemi

(Dorothy)

Dorothy never misses. Imbued not with story but unhinged encounters on and off the network, where characters upload videos and tap out poems, this wildly immersive, monologic book wears skin-slipping syntax like diamonds, fur coat, champagne and pirouettes around your office when you’re sleeping, summons weird dreams, and it knows when you’re awake. But a warning: it takes a strong stomach to turn these pages.

Indigo

by Clemens J. Setz, translated by Ross Benjamin

(Liveright Books)

Equal parts Lemony Snicket and Harry Potter as rewritten by Thomas Pynchon for a line of Marvel comics. Using a troubled, perhaps murderous, Clemens J. Setz as meta-narrator to investigate purported “relocations,” the book alludes to the New Age concept describing gifted kids, and is chocked full of memorable digressions on the nature of distance like the social hierarchies of rats. Beware the Ferenz!

His Name Was Death

by Rafael Bernal, translated by Kit Schluter

(New Directions)

A blast from the past. I greatly enjoyed reading about mosquito language and society as learned by a “recovered” alcoholic who, living alongside aboriginals in the jungle, arms himself both figuratively and literally with this knowledge. Something traditional sci-fi, something Animal Farm in its composition, gimme authors that take big, allegorical swings like this.

Mood Indigo

by Boris Vian, translated by Stanley Chapman

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Tried a couple of times to sit through the Michel Gondry film of the same name, but the book’s version of events are more tragic and darkly clever. In the new year I hope to wade into the disturbing river of Vian’s last novel Heartsnatcher, which titular implement makes gory cameos in this novel and other books.

—Jason Teal, author of We Were Called Specimens and editor of Heavy Feather Review

The Maze of Transparencies

by Karen An-hwei Lee

(Ellipsis Press)

What a gift of language. This book is a dizzying and beautifully-rendered philosophical exploration of technology and its influence on modern life. Beautiful. Difficult. Genius, truly.

Gnome

by Robert Lunday

(Black Sun Lit)

I picked up this book at the Deep Water Literary Festival because it’s the name of the protagonist in my play Kinderkrankenhaus. That’s it. Sometimes you get lucky and find treasures through nothing but a whim. Lunday’s Gnome is a collection of fragments about corporeality and what it is to be someone inside this flawed machine. I loved it.

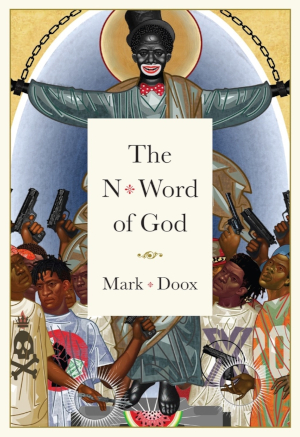

The N-Word of God

by Mark Doox

(Fantagraphics)

A graphic novel about Black symbols, stereotypes, and iconography. Doox’s work is social commentary that is in equal measure beauty and sadness. I read this book in late 2024/early 2025, and it has stayed with me across this entire horrible, resilient, otherworldly year.

—Jesi Bender, author of Child of Light and Crux, and list-wrangler

Jesi Bender is an artist from Upstate NY. She is the author of the novels Child of Light and The Book of the Last Word (Whiskey Tit), the plays Crux and Kinderkrankenhaus (Sagging Meniscus Press), and the poetry collection Dangerous Women (dancing girl press). Her shorter writing has appeared in FENCE, Sleepingfish, Exacting Clam, and others. More: jesibender.com.

Image: Film still of Johnny Sims (played by James Murray) from The Crowd (1928), commons.wikimedia.org

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.