In the rare and happy occasion of receiving a new Luke Johnson poetry book, one is ready to be floored. Those of us who have read :boys and Quiver know what we will get; it is not predictability, but surprising turns and brilliance. As we turn the first page of Distributary we encounter: “For you, my love, I swallow / this knife. & if not this knife / a bushel of swallows.” Already we have song, cadence, power, inertia. We are inside the fire instantly, feeling sting and flight. These poems bring us in and smash us into a glowing pulp, they force us to examine ourselves, our motives, our ghosts, our dark pasts, our hidden fears flaying off our skin. These are not easy poems and thank God for that. They make us look inside whale carcasses, pig bellies slick with killing, deaths with feathers and fins, and create a space for transmutation of grief, an alchemy done while chewing on one’s own shells: “there is a beetle / that eats its husk / … as it burgeons out / a brighter color.”

These poems demand engagement as they dance and thump and soar. You will need to bring your work gloves:

But no

matter the door there is always a shovel. & no matter

the shovel there is always a loss. & loss is a crater

where the living reside. Yes—someone has to dig.

For many of us who have had to process grief and mourning in this life, these poems see us and our blisters attempting to dig through the trauma of parental abuse or detachment, alcoholism, and the small daily deaths of parenting. Stories of witnessing death from a child’s perspective are woven into images of a father witnessing death with his son. As a child, the boy sees his father killing animals, not with triumph, but with an innate sadness: “He / was weeping while / he cleaned his gun.” Images of a father slicing open a pregnant dear and the fetus sliding into the river, then sliding into family members which were also lost:

My

daddy in the dark

wood

asking where his

brother is

and why the lake

won’t cough him

back.

The babies?

He cut

them clean.

The son, now a father, views the body of a dead baby humpback whale with his son. This death was not a killing as much as an encounter with the finality and unfairness of death in the mind of a child:

That night I put the bullet in a pocket of mud, and as I planted it heard my son cry, the sting on his tongue: throbbing. Why am I telling you this? I stood before the shell of that beast on that day in July and whispered sorry as I told my son spit, his mouth flooded with ruin.

The bullets which are lodged in the doe are now in his son’s mouth. Generational patterns of what is killed or denied or eventually regretted are unravelling in our bodies and our words. What is safe when the random guiltless children are dying? As Johnson states: “and my son obeys / with a gaze like Gaza / smoldering. Not a single / bird alive to sing / the living from the shatter.” Also, what is safe for a father when his daughter contracts an illness which he is powerless to stop?

My daughter says it starts as a stab than morphs to a shake, radiates into her bones. Says Didn’t God get it? When Abraham offered Isaac others would follow. Even the earth would agree.

This poem is spun with images of a baby narwhal who becomes stuck in the ice and the father spears it, of an egret who devours its own young, of a group of 22 children swallowed in a mudslide, of an elk skinned by his father. All of these children taken by the father, or the Father. In the same poem he states: “God no longer will grieve.” Johnson is digging into the hillside attempting to rescue the children but his shovel is also a gun and a horn and a sharp beak. There are too many deaths here in the past and in the present to be able to justify or forgive or swallow. What good is grieving if there is a continuation of the dying and the suffering? And who is the God who will no longer grieve? Is it the father, the son, or the ghost? And how do we dig it out, as he sings: “But what do we / make of those / we’ve lost / blurring in the rain?”

Johnson may not find a complete answer to this in his glorious book, Distributary. He does come to terms with the violence and silence his father shot into him, passively. He will not continue this cycle:

when my son asks

for a plastic gun,

I show him

a monarch

or stream,

a hollowed trunk

he can climb into

& wear

like a wild corset.

The gun has been transformed into a body growing, a hollow place we live and decide to grow. As Johnson states in his final poem, it is time to stop digging, rest, bless what is still alive. Time to build rather than bury:

Bless the build, the bridge,

the white noise whittled

from the body’s blazed tremolo.

The technical chops and interweaving lyric of Johnson’s poetry are not to be underestimated, especially in Distributary. His work pushes the definitions of how poetry is defined at the most current time. And it all comes from a place of sweat and bruise and grit. He has dug something out for us. And the treasures are dark and wonderous.

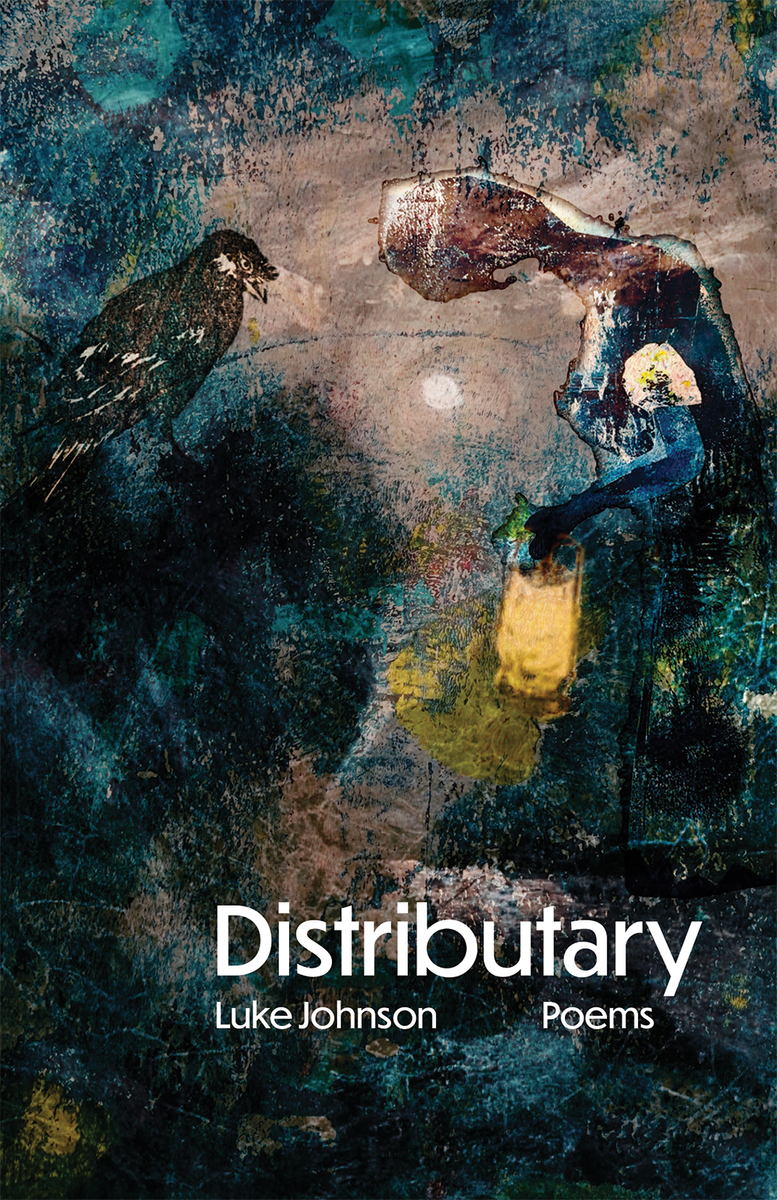

Distributary, by Luke Johnson. Huntsville, Texas: Texas Review Press, September 2025. 116 pages. $21.95, paper.

Scott Ferry helps our Veterans heal as a RN in the Seattle area. His most recent books are 500 Hidden Teeth (Meat For Tea), Sapphires on the Graves (Glass Lyre), and dear tiny flowers (Sheila-Na-Gig).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.