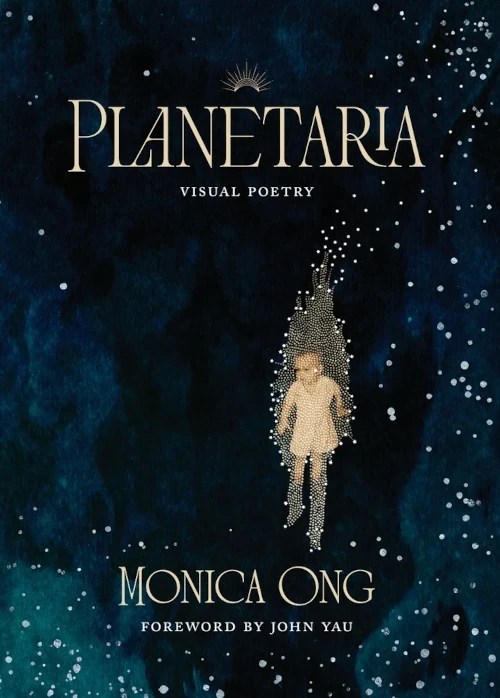

In Monica Ong’s newest book of visual poetry, Planetaria, she doesn’t just write poems, she constructs systems. Drawing from astronomical charts, family photographs, speculative science, and myth, Ong builds a constellation of visual devices that call us into orbit. Her poems are not static pages but interactive mechanisms; volvelles, planispheres, and family photographs shape the formal logic of each page. And, at the center of the book is a speaker who moves through inherited archives, both familial and scientific, layering them into a personal palimpsest that reframes astronomy as a language of intimacy, loss, and reclamation.

Planetaria is organized by the phases of the moon, a structure that stages the speaker’s gradual illumination. At the midpoint of the book, a full moon is printed on the front side of a page. When turned, its light outlines a collage of Ong’s face on the reverse, creating a visual emergence that mirrors the speaker coming into focus. This kind of precise design recurs throughout the collection, revealing Ong’s remarkable ability to shape a visual form that amplifies the poem beyond the text itself. In Ong’s hands, form is not ornamental. It becomes a mechanism for revealing. Her poems write into structure, using charts, constellations, and archival formats as scaffolds for meaning. Ong’s commitment to the visual expands what the poem can hold, offering a model for future writers who see form not as limitation, but as possibility.

Ong allows her visual forms to act as emotional instruments, guiding us through complex relational dynamics. In “Syzygy,” she aligns the speaker’s experience of parenthood with the astronomical configuration of the sun, moon, and earth. The poem draws a quiet parallel between the physics of orbit and the gravitational pull of family. The speaker is both within and beyond this alignment, witnessing and participating in its pattern. As the bodies eclipse one another, so too do presence and absence shift in the poem:

Partial Eclipse of the Sun.

When is a daughter no longer a daughter?

Penumbra, a finger touched eye. We live entire worlds beyond a mother’s periphery. Without Diagnosis, hers is a path of totality. We just want to be seen.

The visual stillness of the layout contrasts with the emotional motion beneath it, allowing the poem to speak through arrangement as much as language. The celestial metaphor becomes more than image. It offers a system of proximity, occlusion, and revelation. The eclipse frames a question not only of visibility, but of relational clarity: what is lost or misunderstood when one body passes before another? In this space between light and shadow, Ong gives voice to the desire to be recognized, not abstractly, but with full emotional and physical presence. Thus is the power of Ong’s visual poetry. The text does not simply describe distance. It embodies it.

Later, in “Her Hypothesis,” the relationship between image and text deepens. A prose block addresses a “you” caught in the labor of gender and legacy, circling around themes of performance, maternal expectation, and the exhaustion of explaining oneself within systems not built to hold her:

Lines are being drawn in the sandbox and relatively speaking everywhere you stand is marked upstage. Binary and other double stars and star clusters gather.

The prose circles meaning, performs an act of gender and tradition, and invites a reading through perspective—but only just. This long prose block sits beside a collage of Caroline Herschel’s star chart over a childhood photograph of Ong’s eldest paternal uncle. As prose and star-map reflect and juxtapose, the stars echo the text’s clustering language, inviting us to ask what child rests beneath the surface of this constellation. Ong asks us to hold the visual and verbal together, to question what lies beneath inherited knowledge. As the speaker reflects on perception, the stars themselves become part of the poem’s grammar. Rather than stabilizing meaning, Ong’s design insists on a layered kind of looking. The visual elements do not simply accompany the poems. They are the poems. In pieces like these, Ong reframes visual poetry not as novelty or departure, but as a method for exploring the layered conditions of intimacy, motherhood, and memory.

Ong’s interest in visibility is not limited to personal or familial history. It extends outward, toward a larger reimagining of scientific legacy. In “Her Gaze: In Tribute to Caroline Herschel,” Ong uses ViewMaster slides to reframe the overlooked contributions of the first woman to discover a comet. Caroline Herschel, a nineteenth-century British astronomer, is often remembered as the sister of William Herschel, but Ong shifts the lens. Through repurposed celestial maps and carefully placed text, she allows us to literally see through Caroline’s eyes. Her tribute to Herschel becomes a quiet act of correction—one that parallels her own experience as a visual poet working outside traditional recognition systems. The use of a ViewMaster to perform this act of reclamation captures the brilliance of Planetaria, while also highlighting the paradox of translating such tactile, layered work into the flat confines of a book.

When we engage with Ong’s visual poems, we are asked to do more than read. We must seek meaning across fragments of language scattered through diagrams, constellations, and photographs. This act of assembling meaning is a form of unrecognized labor, mirroring the very themes Ong explores. Her piece “The Dark Side of the Moon” posits the unrecognized labor of women, like Chinese American physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, through the medium of a lunar map, illuminating an uncredited history through visual structure. In Ong’s work, the medium becomes the message. The chart, the image, and the layout are essential to the poem’s emotional and political force. In this sense, Planetaria belongs to a tradition of visual poetry that does not simply aestheticize language. It uses language to trouble systems of power, including familial, scientific, and institutional ones.

The final pages of Planetaria document the work as it exists beyond the book—pillows, ViewMaster reels, gallery installations, and diagrams projected across walls. From her Planetaria exhibition at the Poetry Foundation to the handmade objects she constructs through her micro-press, Ong’s practice insists that the poem is not confined to the page. It can be held, rotated, projected, and worn. These moments remind us that the future of poetry will not emerge from within tradition but from its edges. When we hold Planetaria, we are also holding its paradox. A book bound in covers that resists containment. A visual poem printed on a page that wants to be seen in motion. And yet, perhaps this is precisely the role of poetry—to show us the limits of what we think a poem can be, and then step past them. Ong’s work does not just imagine the future of poetry. It makes it possible.

Planetaria, by Monica Ong. Proxima Vera, May 2025. 100 pages. $40.00, paper.

Beau Farris is an experimental writer from Colorado and a recent MFA graduate from the University of Colorado Boulder. His work explores the interpretive potential of form, often employing visual poetry, conceptual structures, and constraint-based writing. His poetry has appeared in The Indianapolis Review, Variety Pack, English Language Notes, and elsewhere. When not writing, he enjoys making mixtapes no one listens to and texting his sibling prose poems by accident.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.