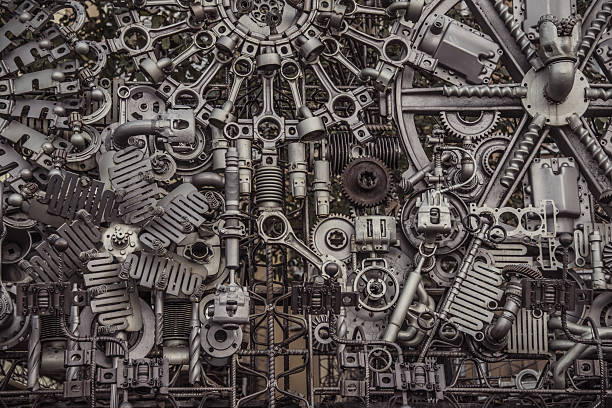

Secret Machine #1

The machine’s pull cord, not unlike a lawnmower or teddy bear’s, winds for miles. It’s resplendent, glossy like fishing line still wet, a sharp burst of blinding light when viewed from the right angle. It disappears periodically into the earth’s dry clefts, only to reemerge somehow brighter. The pull cord bows in several sections, burdened wide by hay strands, candy bar wrappers, and aluminum soup cans. Maybe with enough force, it would play twinkly music or rattle rough like miner’s lungs.

You open the suitcase. When viewed under a portable microscope, the pull cord is comprised of an equidistant series of teeth connected in plastic molding. A violinist, I encourage you to grab a random section. Pull smoothly, evenly. Imagine holding a steady note. The hypnotic locomotion resembles a jaw mid-grimace. The mouthguard in my pocket shakes, recognizing the ebb and flow of nightmare grind. When your arm is fully extended, the molding shatters. Teeth scatter, periodically reenter the field of view dragging various objects. Dandelion fuzz. A housefly by its pieced wing. Corner of wilted corn husk. In this way, the teeth mimic ants, oblivious to their own diminutive weight.

When I pull back and rub my eyes, the pull cord was never not solid. As with any living thing’s appendage, it cycles between stillness and restlessness. You hypothesize that the machine has a tail. Miles away—where the machine appears butte-like in the pixelated haze—we discover a metal ring on the pull cord’s end. It imprints small haloes into the dirt. The haloes are the circumference of an animal’s paw, small god, or tangerine. You point to trident imprints inside the haloes, mimic a killdeer by hopping across a small section of bare acreage like a plague game.

My next guess is bindle. I cannot yet determine whether the ring or machine is the bindle’s end. The machine is the obvious choice. While not sack-like or bandana-sheathed, it has weight and envelops smaller machines, bodies, chairs, and perhaps a small cafeteria. When I stretch the pull cord taut, you question whether there’s any difference between a bindle or yoke.

You retrace your steps to the machine’s base. You crackle through my walkie talkie, comment that I’m dissolving into drought dust and crow shadow. The horizon bulges slightly, barely acknowledging my presence. Then you notice: the machine’s innards accelerate. There’s a whir like a breeze stirring but not having yet arrived. You comment that it’s difficult to distinguish between my radio static voice and the machine’s throat clearing. I’m yanked forward. We both hear metal against rock as though the machine is moving. The machine thinks I’m beautiful vanishing. You suggest I just let go.

Secret Machine #2

The sons, three in total, didn’t survive childbirth. Each emerged wearing a radiant placenta helmet, tied airtight around their throats, tufts of messy hair lovingly patted goodbye.

The sons survived childbirth, so they crawled into the driveway pocked with shallow impressions from freight laden semis. The great weight of turbines, boilers, sheets of unshaped metal conveyors, backhoes, forklifts, and the occasional blast proof door. The boys cradled inside, angles soft like a mother’s embrace, and began to drown in small waves of leaked oil, toes afloat, white as ocean bleached buoys. Then, they flash burned in the noontime simmer, charred into angels with flickering, abandoned eyes.

The sons survived celestial transmogrification, so the machine taught them to dance, first by gently tugging on their flannel sleeves and complimenting their freshly waxed leather shoes. When insinuation and suggestion proved insufficient, the machine undressed them. Buttons pinged off metal surfaces like diminutive hailstones. Nearby workers stored belts and denim jeans in first aid cabinets, useful as tourniquets and makeshift bandages. Shoestrings supported the odd Christmas ornament or safety award. Naked but for knickers, the sons stood steel-struck as the machine coated them in chrome, branded lever and gear diagrams across their stomachs.

The sons survived sudden onset sigilitis, so the machine blindfolded them, blaring directions over its loudspeakers. They marched around the machine’s entire perimeter, memorizing every panel indentation, rusted rivet, or sudden divot where a culvert’s ridges briefly appeared. At dusk, the machine allowed each to remove his blindfold to observe strangle hooks orbiting overhead. The soft whoosh of never-arriving wind tempted each to believe the heat would abate. The machine promised that if the boys prayed fervently, the dangling straps would unfold into an owl or buzzard.

The sons who survived their carrion tenure, so they sought a piece of silver moon they heard strike nearby, a nameplate onto which S. J. Farley & Sons could later be etched, affixed at the machine’s pinnacle that, over time, emerged from scaffolding. But the cratered expanse shone dimly at all hours. With the moon sliver elusive, they settled for a piece of thick bark, ashy and coated in lichen, lonely in its own cavity. It sufficed as the machine grew though its adolescence, an ever-growing heart bountiful with coal and spark.

The sons that survived the kindling experience, so they were overwhelmed, not by the heat but that they proved inflammable no matter how closely to the flame they danced.

Jason Fraley is a native West Virginian who lives, works, and periodically writes in Columbus, OH. Current and prior publications include Salamander Magazine, Barrow Street, Jet Fuel Review, Quarter After Eight, Mid-American Review, and Okay Donkey.

Image: istockphoto.com

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.