When I was sixteen, I had a fat crush on my boss at the grocery store where I scanned boxes of cereal and punched in produce codes for five dollars an hour. He was twenty-four, a community college dropout with dyed-black hair and a tattoo of a guitar stretching out over the back of his calf, the frontman of a mediocre cover band that played the local bars. In other words: so cool.

When he asked for my number I wrote it down on the back of a discarded receipt (so so cool, like I didn’t even care!), and he started calling me drunk so I could swoon over his band’s interpretations of Eve 6 and Blink-182 and, my favorite, “The Boys of Summer.” I’d never heard of Don Henley and the only alcohol I’d ever tasted was the wine at church, but I recognized the song from The Ataris version on my Now 14 CD. “Remember how you made me crazy! Remember how I made you scream!” we’d both yell, into our respective flip phones, mine bedazzled with sparkly pink and silver decals arranged in a star pattern (so cool, too).

After his gig we’d stay on the phone for hours while he guzzled Bud Lights and I ignored my homework. I’d sit on the floor in the basement so my parents couldn’t hear, teasing him for making proclamations such as “Recycling is actually really bad for the planet!” and “Laundry is now obsolete thanks to Febreeze!” He was crazy, I whispered, but I wouldn’t know—my mom still did my laundry, left my JV volleyball uniform folded neatly on my bed.

Back then I was starving for a friend—someone, anyone, to laugh at my jokes, smile easily in my general vicinity. He was charming, sure of himself, with a girlfriend who went to college two hours south and a roommate who managed the produce department. They lived, conveniently, in the apartments right across the street from my high school, which is where it began: first as playful rounds of Guitar Hero (less cool) and then as slow dancing to Jack’s Mannequin (cool) and then one day I was falling asleep on his couch and there was his tongue in my mouth, so rigid and confrontational I mistook it for a thumb.

I had never kissed anyone before. I didn’t know what I was doing, or why. I knew I didn’t like it, or that I only liked it in theory, or that I liked it because I knew I should like it, because I wanted to be liked. I knew there was something off about it, which is why I told my mom I had to study, all those mornings I left with her van at six- instead of seven-thirty so I could swing by his apartment before calculus. I knew it was off how I’d park and sit there for a few minutes, as if maybe, this time, I wasn’t going to go in. Because I didn’t have to go in, and I kept going in. When I knocked on the door he’d answer in his boxers, shushing me so we didn’t wake up his roommate, and in his room the January Wisconsin sun would be struggling to rise against his curtains and there was something off about that, too, and all of it: his hungry fingers dancing along the waistband of my jeans, those dingy curtains the color of sweat on a white T-shirt, the guilty way he’d stare at me, after, chuckling, “You’re gonna get me in trouble, Jack.”

Jack? Only my mom called me Jack. Something vaguely not OK was happening, here, but I wasn’t able to articulate it, so I pinned it on the most likely culprit. “I’m such a slut,” I tried, in my journal, in pointedly red ink (we were reading The Scarlet Letter in American Lit). I tried confiding in a classmate. “You’re such a slut,” he confirmed, not unkindly. I didn’t talk about it with anyone anymore, after that, and anyway it only lasted a few weeks; by spring, he replaced both me and the college girlfriend with a fellow cashier who was on the cusp of high school graduation. She tied her bottle-blond braids with white ribbon. I listened to “The Boys of Summer” while stalking their smiling Facebook selfies, dragging the cursor over each one of the comments: “Awwww!” “So happieeeeee!” “Could you BE any cuter? You’re making me sick.”

This was 2006, a full decade before #MeToo would enter the mainstream consciousness, and I was a young sixteen. Assault was something that happened on the Lifetime movies I watched with my mom. Rape was something that happened in dark alleys, between strangers. Had something bad happened to me? Some gray-area kind of bad that nobody had ever bothered to warn me about? No. Yes. Maybe, or maybe only sometimes, or maybe all of the above.

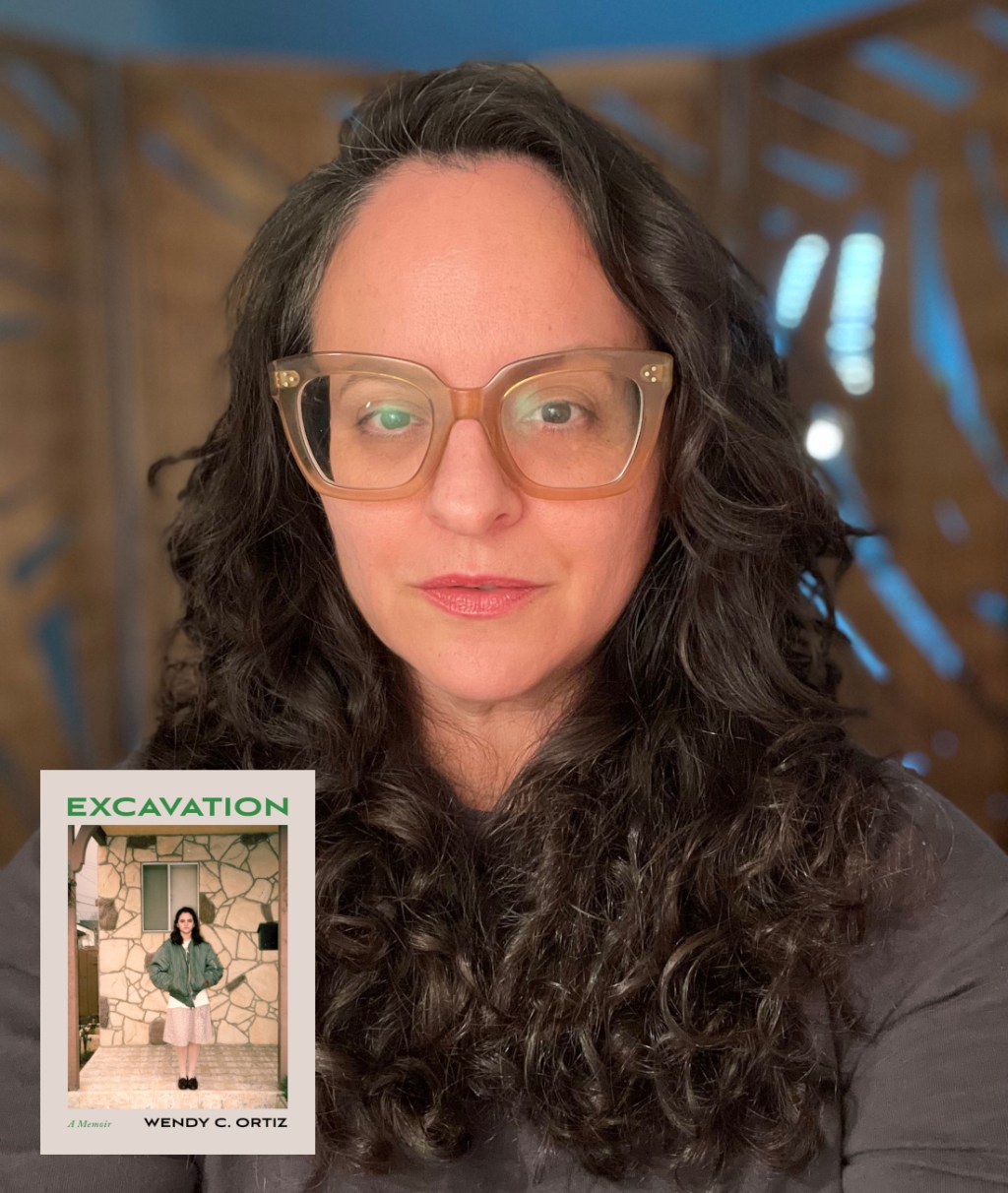

This is the kind of territory Wendy C. Ortiz tackles in her memoir Excavation. Originally published in 2014, Excavation is being reissued by Northwestern University Press in Spring 2025. The first time I read it I was newly twenty-four, newly out, and newly realizing, not without alarm, “This is how old he was when he was hooking up with high-schoolers.” Excavation, in which Ortiz recounts a years-long relationship with an older English teacher that began when she was just thirteen, cracked open wells in me I hadn’t even realized I’d sealed.

That kind of psychological reckoning is familiar terrain for Ortiz, whose volunteer and work experience ranges from teaching creative writing to youth in juvenile detention facilities to training in psychotherapy at a community counseling center. She holds an MFA in creative writing as well as an MA in clinical psychology. Since 2017 she’s been a psychotherapist in private practice.

Since Excavation’s first edition was published, she’s adapted a play based on her essay “Spell,” in collaboration with director Meera Menon; and published two more books, Hollywood Notebook and Bruja, both of which are being reissued alongside Excavation by Northwestern University Press in 2025. Most recently Wendy has served as guest faculty in creative nonfiction in the MFA Program at CalArts and published essays in Joyland, BOMB, and Pleiades.

When I first read Excavation, it marked a beginning for me, too—of not only understanding what happened in 2006 and continued happening, to greater and lesser degrees, for years afterwards, but also doing something with all of it beyond just putting it away. Reading Ortiz’s memoir was one of the first times I remember thinking it might be worthwhile, even if incompletely or inconsistently or unreliably worthwhile, to start writing true stories of my own.

I had the opportunity to email with Ortiz about writing trauma, writing queerness, and the always destabilizing, sometimes valuable experience of trying, over and over, to mine memory for difficult shit—then get it all onto the page in a way that is meaningful.

Jax Connelly: Every time I read Excavation, I’m struck by your ability to honor your teenage experience without “contaminating it” with hindsight. I think it’s so easy for us, as CNF writers, to fall into the trap of only seeing what we wanna see—seeking out only the evidence that will support some kind of pre-selected narrative we’re trying to uphold. I wonder if you can start by discussing how you managed to write as and about your teenage world without the judgmental lens we so often employ when remembering our younger selves?

Wendy C. Ortiz: It took many years (and years of therapy!) to get clear with myself about my intentions about writing this book, and how I wanted to tell the story. It was always clear to me that I would be writing something potentially challenging. I knew I didn’t want to put labels on the characters that would flag how the reader is “supposed to” feel about them. I wanted to show how an antagonist, or a villain, like Jeff, could be more than just a perpetrator, which is why it was so difficult for my teenage self to completely see or understand what she was involved in. I think, too, that a lot of my training as a therapist has prepared me to look at my younger self with different eyes—more non-judgment, more compassion.

JC: I’m similarly impressed by your ability to honor that teenage experience without romanticizing it. I read Excavation as a reckoning with what happens when we don’t allow teenage girls safe spaces to explore their sexuality and the fact that they’re becoming sexual creatures. Can you speak to the role of gaze, in the memoir—references to being watched, being seen, seeing the self from the outside—and the way that interacts with the equally important moments of sinking into the embodied experience of being a teenager—the lip biting, the heavy sighs, all the ways you dig into the ideas behind this great description: “Puberty in a nutshell: I was regularly high, hormonal and passionately angry”?

WCO: First, I love this: “I read Excavation as a reckoning with what happens when we don’t allow teenage girls safe spaces to explore their sexuality and the fact that they’re becoming sexual creatures.” YES. This is how I also wanted it to be read. So thank you for this. I don’t see this very often when folks remark on the book.

One of the things I noticed as I was writing the book was that I felt uncomfortable writing about me, for example, gazing at myself in the mirror. And yet I knew that was as important as anyone else’s gaze, which is why there is an (excruciating to me) chapter that involves me standing on the toilet seat gazing at my body in the mirror. There are so many interruptions of a young woman’s own gaze at herself. Like, what if I understood myself more through my gaze than other people’s, particularly men’s? Well, I didn’t get much of a chance to—there were always men interrupting my burgeoning sense of self with their gazes, their comments, their desires and projections. And at the time I only could mostly conceive of myself as an object because of these interruptions. How could a teenage girl use this “power” constructively?

When I write about walking away from Jeff’s house, angry because my own pleasure was overlooked in a particular sexual encounter, I’m writing about the teenage girl aware of her own desires, potentials, and feeling frustrated that there was not a space to expand or explore that would also be safe, respectful of my humanity.

JC: I once heard some writing advice that went something along the lines of, “In creative nonfiction, you have to be willing to throw yourself under the bus further than you throw anyone else you’re writing about.” I think that’s really great advice in terms of gaining the trust of our readers and training ourselves to look beyond our internal realities, but I also think it becomes tricky when we’re writing trauma. I have two related questions, here:

First, in writing about both Jeff and your mother, how did you avoid the impulse to villainize? Of course as writers we always strive to represent people as multidimensionally as possible, but what are the limits of empathy, if any, when writing our true stories?

WCO: I really do have ongoing conflicted feelings about the two “characters” you mention—Jeff and my mother. There have been different times in my life when I’ve had a lot less empathy toward them than others. It shifts and changes, still. Every person, and in this case, writer, gets to work with their own empathy bandwidth. I’d never think of imposing a limit on empathy on or for anyone, understanding that people have their own experiences that inform their understanding of and use of empathy in their lives.

Like, I have zero empathy for the president of this country. Then I hear Gabor Maté speak about trauma and identify that same president as “full of trauma,” “you can see it in his face,” and I go, yeah, true. Does it increase my empathy for him? For a moment, maybe. Eventually I’m back to loathing him and not being able to imagine engaging with his humanity (which I almost wrote in quotes—“humanity”). Empathy can shapeshift. I just don’t want it to disappear.

JC: Second, I’ve recently been thinking a lot about unreliable and “unlikable” narration in my own writing—how to push back against the expectation that we make ourselves, as narrators, unimpeachable, “perfect victims,” when we’re writing trauma. Can you discuss the importance of complicating the black-and-white predator/prey trope on the page?

WCO: It’s only as an adult that I’m able to understand the deeply fucked-up reality that as a young Mexican American girl, I would never be considered a “perfect victim”—a designation that is typically reserved for white women and girls. And then there are the ways in which I did attempt to bring reliable adults into the situation and they either refused or denied to themselves what was happening and didn’t intervene. There is no way to construct a “perfect victim” because it’s a myth. So why not lean into the truth of the messy, complicated ways stories of sexual abuse actually play out? A perfect victim is bullshit and boring and a lie.

JC: Although Excavation advances steadily through the 1980s, this is not a linear telling—it’s messy, which feels very queer to me (more on this in a sec). There’s a sense of coming up for air in the “Notes on an Excavation” sections as well as the bits of lyric flash which are interspersed throughout, such as “Home.” Every time I read this I find myself grappling with an ongoing sense of being lost and then found and then lost and then found again. How did you decide this recursive structure was the best one for this particular story, and what did that look like as you were actually writing it?

WCO: What you’re describing—feeling lost and then found and then lost again—is a perfect parallel to the experience of being a teenage girl who is asked to behave as though she were an adult when she is in fact a teenage girl—the moving between those worlds. It took me a long time to understand that I needed to offer breaths between chapters. At first it was just a chronological rendering, but that alone doesn’t let the story breathe, or suggest that anything changed or was impacted by what happened. So when I finally understood I needed to bring my readers back from the particular hell I deposited them in, it was easy to write the interstitials (as I think of them).

JC: Explicit queerness is hovering around the edges of this book, but I’ve always read it as implicitly queer from cover to cover. I think that’s related to the structure, the slipperiness of time, but also the multiple “I”s that seem to be present throughout. The “I” is repeatedly fractured, fractalized, introducing this concept of self as plural and fluid, and toward the end of the memoir I sense that the boundaries between those siloed selves begin to blur and collapse. I think this is something we all grapple with when we write creative nonfiction—the “I” of reality vs. the “I” that ends up on the page and all the “I”s in between. How did you approach writing this kind of complicated self-representation into reality?

WCO: It makes me want to cry to read that you have always read it as implicitly queer! When it first came out, I feared that my queerness, the queerness indeed present in the book, would get lost. When I put the book forward as an entry to the Lambda Literary Awards for creative nonfiction in 2014, I imagined that for many readers, they’d be like, Why? What’s queer here? (Then I remembered I have no control over how people read the book, so …)

I once read a description of my work as “polyphonic,” and that really resonated. There is no one fixed “I” here. I assume that’s true of most people. My books will always be written in the voice that seems most fitting for the content, and that may be from the “I” who is a 14-year-old, the “I” who is a 28-year-old, and so on. When you ask about the “approach,” I can only see it as a choice to allow these voices in and out. It feels natural to me, but it’s a choice. Luckily an easy one.

JC: There’s a major thread in the memoir about the importance of language—what happens when we don’t have the words to describe and transcend trauma, or when the words we do have don’t seem to fit our experiences. This is discussed explicitly—“I was learning in these rooms and in college classrooms the words for the situations I had endured as a teenager—as well as more obliquely in lines like “‘wrong’ was just something in quotation marks.” As a therapist and a writing teacher as well as a writer yourself, I wonder if you have any thoughts on this idea of writing as processing, finding the words to make sense of the things that happen to us. What is the unique power of writing as a tool for self-discovery, an organizing principle, a tool for catharsis? What are the limits?

WCO: Sometimes it takes years to get to a place where you have the best language to describe what happened. For years part of my process was writing fiction that took some of the bigger situations in the books—like power dynamics—and fictionalized what I understood about them, via characters based on me and people I knew. Once I was talking about what actually happened to me in therapy, I became more and more comfortable not using fiction as a way to make sense of it.

So, yes, I see writing as a tool for self-discovery, and definitely catharsis, but it must undergo a shaping, and sometimes needs space between catharsis and publication (I’d say, most often). I’m not a fan of calling writing “therapy”—it has therapeutic elements, but it’s not therapy. This makes me think, too, of how readers will sometimes describe writing they love as “raw.” Raw to me is closer to catharsis. There’s no editing of true catharsis. I am, and my work is, in fact, well-cooked. It has had space and time, and it has been shaped and edited.

JC: There’s a line about halfway through the memoir—“I learned about love that was not like the love I had been taught in my relationship with Jeff”—that strikes me as a more accurate restatement of a sentiment popularized in bildungsroman The Perks of Being a Wallflower: “We accept the love we think we deserve.” That line has always bothered me, because I think it’s more accurate to say we accept the love we learn—as you write, the love we are taught—and then we have to unlearn it. In a way I read this book as an unwriting of traditional trauma narrative, or at least an unwriting and then a rewriting/reclaiming of experiences that cannot be trapped inside words as easily as others. I wonder if you can speak to the power of writing as a tool for unlearning as much as learning?

WCO: I’m not sure if this is purely personal, but I’ll talk about this from that place. My personality, or my temperament (?), is one in which I’m often the “odd one out” or have completely different conclusions than a number of my peers about the same topics. I will “learn” what is out there but usually come at it from a place of trying to work out “what’s wrong with this if everyone is doing it, believes it,” etc. It’s like coming at it from a place of unlearning to begin with. I’m not sure I’ve ever articulated it this way, but that’s what I notice. There is so much to unlearn, including some of what the traditional trauma narratives offer.

JC: Excavation first came out in 2014, two years before Trump was first elected, three years before #MeToo entered the mainstream spotlight, and six years before the pandemic. The reissue of Excavation is coming out during Trump’s second presidency. Any advice or words of encouragement for writers who are struggling to stay motivated during this really isolating doomful time?

WCO: Focus in on the practices that you know, for yourself, that help keep you grounded and balanced. Keep coming back to those. You’ll need these practices for the rest of your life, so if you don’t know what those are, be curious, and find them. These kinds of practices can be the foundation of motivation in the long-term. We need you—so please take care of yourself and then help take care of others—we—all of us—need to be a part of that ripple effect, constantly.

Jax Connelly (they/she) is an award-winning writer whose creative nonfiction explores the intersections of queer identity, unstable bodies, and mental illness. Their braided, collage, flash, and formally experimental essays have received honors including four Notables in the Best American Essays series, Nowhere Magazine’s Fall 2020 Travel Writing Prize, and first place in the 2019 Prairie Schooner Creative Nonfiction Essay Contest, among others. She’s been a finalist in contests at The Bellingham Review, Black Warrior Review, Fourth Genre, and New Letters, and her work has also appeared or is forthcoming in The Georgia Review, [PANK], The Rumpus, Hunger Mountain, Pleiades, No Tokens, and more. They live in Rogers Park, Chicago.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.