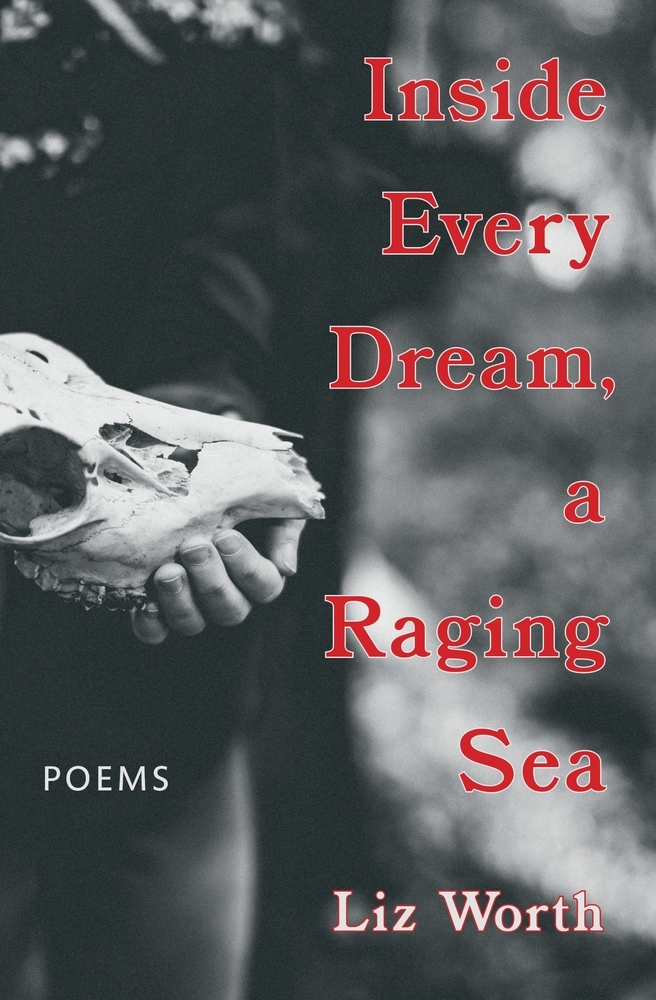

Liz Worth’s Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea is a lovely book of poetry that’s sure to intrigue those who are interested in the natural world, the otherworldly, and the emotional realm. Across 80 plus pages, Worth writes us through an experiential landscape, hoping in and out of experiences, mixing them it with spiritualism and observances. Time passes for the speaker—page by page—and we are transported through the portals of heartache, longing and healing.

We start off with “I Don’t Want It Like I Used To” and are introduced to a three-part poem that confronts a “you.” We don’t necessarily know who this “you” is, but our speaker does and pointedly describes their struggle in what feels like a described deterioration of life force. It isn’t necessarily clear what has taken place at first and why this poem is pained. However, the confession to the discomfort is refreshing yet writhing, slowly teasing out the memory as blood- a heavy currency.

We find that there are several “yous” throughout the book, lingering in memories of childhood, relationship, solitude. They often haunt the speaker in waking life and dreamscape. This is the main content of the book and, if you are into this, you’ll find that Worth carries this theme consistently and well. Relationships are never pigeonholed as purely romantic with this book; rather its strengths are within poems that reflect on the self. The shifting self- plagued by time’s passage- is especially strong to me in “Memory of Place,” “Black Annis,” and “Seafoam.” With “Memory of Place,” I find myself repeating stanza four:

The Woman next door died three nights after you left. You

remember how she used to knock on the wall when the TV was

too loud. After I heard the news, I lay in bed and knocked back,

just to say goodbye. I swear she answered me back: tick-tick-tock.

It’s here, along with the preceding poem “Summoning Spirits,” where we start to incorporate more boldly the otherworldly presence; not just memory, but in an unseen yet felt other. These supernatural others work to enliven mundane living as the speaker moves through poems. From this point forward, I see a trend in referencing the occult. It was subtler at first, but Worth present us with poems that now see beyond the veil, even if someone is still alive. As we read on, the veil becomes a liminal space where Worth also weaves in more heavily the dream world, ritual living and occult dealings. If you didn’t know she was into this by now, it’s obvious and potent. Some poems begin tapping more readily into this imagery (“You Don’t Know Me Like You Used To,” “Private Light,” and “Hands”). From “Hands”:

Every syllable a witch, cackling.

When the coven starts to grow, I know

I’ve said enough.

The fullness of the poetry lies in the consistency of Worth’s writing and style. She is largely confessing, allowing us to peek into the mundane with fresh eyes. The language is plain yet has glimmering moments. The speaker is not precious about their faults or fears, just honest without the weightiness of pessimism. There’s longing, an attempt to reach out to grasp at something like a reckoning. We don’t particularly arrive at some salvation by the end, but we don’t need to, and I doubt we would believe it anyway. There’s nothing in Worth’s poetry to leave us wanting. We simply understand that the speaker has this grave need to relive, replay, or rejoice.

As I concluded the poetry, I wondered if there could’ve been more varied poetry earlier in the collection. This is my small critique. Confession is the cornerstone, but there are moments of instruction. There’s a direct lucidness that I wish happened earlier after reading “The Self” and “The Healing.” These feel in control of something, in contrast to earlier poems which ask but never receive; but does haunted sound helpless?

A third of the way into the poems I read something concrete happening despite the ephemeral. The spell work is taking hold. The self-restraint is torn apart or perhaps told to go on vacation for a bit after we reach this point. We also get a bit of change in structure. While most poems read like prose, and we do get more conventional poems in stanza blocks, I feel that these two poems are refreshing, offer visual space and flow well. The breaks feel intentional, and the structure slows down for us to be instructed. Listen to the speaker, not just for a story; there’s wisdom and if allow yourself to reckon with your own “yous,” there’s a reward for you. These poems chant a mantra: repeatable and empowering. The titular poem offers a twist of alternating questions sandwiched between more self-assured lines. It can’t be denied that the speaker grows into self and an acceptance is expressed more thoughtfully as we conclude the collection.

I enjoyed Worth’s poetry collection and hope you consider it. The folklore of living is highlighted in Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea and if you nothing else away: we create our own living lore.

Inside Every Dream, a Raging Sea, by Liz Worth. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Book*hug Press, October 2024. 84 pages. $18.00, paper.

Toni Hornes Sullivan is a poet and visual artist from Baltimore, Maryland. She has been published in Ginosko Literary Journal, 100 Subtexts, and Wooden Teeth. She has been a poetry reader and fiction reader for Welter and Plork, literary journals for the University of Baltimore, and is currently a Student Ambassador for the university. Her writing interests include: relationships, death, spirituality, lineage, memory, mental health, violence, art/music and the Self. She also is interested in writing memoir and micro/nano fiction.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.