And Yet is a written record of a nameless narrator’s effort to make sense of his romantic life. He’s a young adult, busy developing a sense of self, and he sees the way his relationships affect that development. He sees that romantic relationships can foster his selfhood, and also that they can warp it. So he looks to his reading for ideas that might validate his choices, and he writes down the things that strike him.

The book begins with the narrator’s first love and the painful end of that relationship. This lover likes Susan Sontag, and the narrator reads Sontag and other theorists with the kind of seriousness that we bestow on the things our loved ones love. Recommending books is one of the key ways that the narrator and his girlfriends communicate with each other.

The text of the book is chopped up into short sections, measurable in paragraphs and separated by a crescent-shaped typographical sign. These sections mix the narrator’s personal story with quotations from or descriptions of books and articles. I counted, and I estimate that something like 70 percent of all sections in the book are quotations or references, rather than original story. The book never specifies whether the narrator is actually, within the fictional story, writing all these things down somewhere, or how they actually operate in his life.

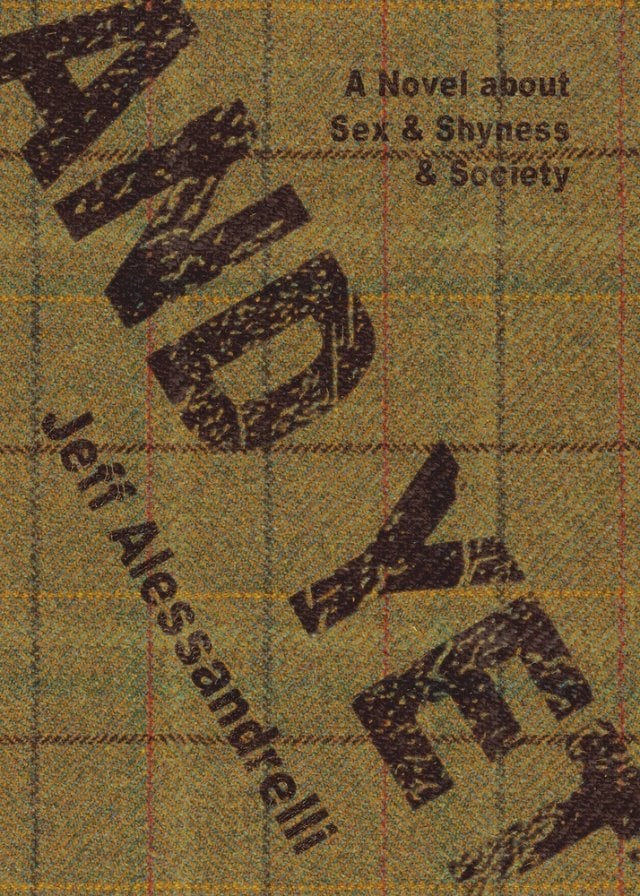

The book’s subtitle is “A Novel about Sex & Shyness & Society,” and the author (in his introduction) and the narrator talk about sexual shyness and describe this book as an exploration of that. But while sex is constantly referred to, it is kept shrouded. Both the fictional narrative and the references seem to be much more about love and connection, the expectations people place on love and connection, how those expectations might be misleading, and the ways that our relationships might warp our personal development.

Most of the characters in the book, especially romantic and sexual partners, are referred to just by a single initial. Yet the three most important girlfriends are clearly differentiated from each other and described with affection and without hostility. I was sensitive to this because I was looking for signs that I should dismiss or mistrust this guy. He himself seems pretty aware of the possibility. He chooses to be celibate for a period, and that period of celibacy is followed by an unwanted sexual dry spell, and he makes a point of raising the modern specters of incels and hikikomoris so that we can see for ourselves that he lacks their toxic qualities. And I was happy to accept that he’s a decent person who I don’t need to worry about. But there was a lack of friction here that I noticed the one time the narrator was really challenged.

During his dry spell, the narrator gets lonely and starts going to therapy. His therapist points out that his reading doesn’t seem to actually help him make sense of things. He just writes down things that relate to whatever he’s going through at the moment. When he’s in therapy, he makes a Sopranos reference about therapy, and starts quoting Tolstoy after his therapist tells him to read “the Russians.” His therapist clearly sees that what we are reading is not necessarily helping him make sense of the world, but is more of a personality type or quirk, where someone consumes other people’s work and outsources their mental life to them, without really growing.

He responds by depicting the therapist as the only non-idealized woman in the narrative. She isn’t what he expected her to be when he heard her voice while making an appointment on the phone. She’s a big woman, tall and “rotund,” and when she calls him out on reading instead of living, he gets defensive and has the first angry thoughts we hear from him, mentally attacking her as an “overweight motherfucker” who can’t tell him anything. I realized, belatedly, that he’s given this therapist a full name, Larissa, and that he describes her moving heavily around her office and eating a granola bar. He develops a long-term clinical relationship with her, continuing their meetings over Zoom after he moves across country, and seeming to attribute his growth to their work together. What his descriptions of her and of their relationship made me realize was that the three important girlfriends in the narrative, whatever difficulties he had with them, were always both lovable and fuckable, and that he was at some pains to get that information across to us.

He says that, thanks to therapy with Larissa, he reads less and has started taking improv classes. But nothing in the style or structure of the book changes—the references and quotations go on at the same density. So it’s a realization that he tells us has happened but that the book doesn’t enact.

This means that, for me, the references and quotations don’t add up to much. (Nor does the author take a lot of prose lessons from the elegant stylists he’s reading.) I’m just browsing the things that struck a guy because they had something to do with his life, and so it’s hit or miss whether I’m going to feel the same way about them. I liked the things about our ideals of romantic love and how they shape our expectations. For example, sociologist Eva Illouz spells out the following assumptions that underlie our cultural concept of “enchanted love”:

1. The object of love is sacred.

2. Love is impossible to justify or explain.

3. Such an experience overwhelms the experiential reality of the lover.

4. In enchanted love, there is no distinction between subject and object of love.

5. The object of love is unique and incommensurable.

6. The person in love is oblivious to his or her own self-interest as a criterion for loving another person.

I liked the way some of the quoted writers make concepts like these visible so we can think about them. On the other hand, I did not care about the episode of the Sopranos where Tony tells his therapist, “You know sometimes what happens in here is like taking a shit.”

The narrative and the references reach a kind of conclusion with a consideration of the book Manhood, by Michel Leiris. The narrator recognizes himself in Leiris’ depictions of his relations with women, and seems to come to rest with Leiris’ “unashamed” exploration of what it means to be a man. Manhood, and shame, have been obliquely referred to throughout And Yet, but the narrator hasn’t used those ideas to frame the project of this book. But Manhood seems to introduce a new question that he can use to think about the next phase of his life. It’s nice to end with the idea that all these books might be providing, not necessarily the validation we seek in them, but the questions that can keep us interested for a long time.

And Yet, by Jeff Alessandrelli. Portland, Oregon: Future Tense Books, April 2024. 280 pages. $18.00, paper.

Ashley Honeysett’s debut book, Fictions, won the Miami University Press Novella Award and the Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year Award. If you want to be a more adventurous reader you can subscribe to her newsletter at ashleyhoney.substack.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.