In 2015, Lee & Low published The Diversity Baseline Survey, giving us a rundown of who’s working in publishing, including small, medium, and large publishers. Their percentages are as follows:

79% White

7% Asian

6% Hispanic

4% Black

1% Middle Eastern

1% Native American

These numbers take into consideration jobs across the board, from editorial to the executive level. You can read more of it here. And they’ve since come out with a 2023 version, reflecting some changes in the field, including an .8% increase for Asians and 1.3% for Blacks, but stasis for others.

If we go ahead and decipher what these numbers mean for the reading public, yes, it looks like white people (mostly men) are in control of what we read. But this is not the biggest surprise given the history of publishing.

In John B. Hench’s illuminating essay, “The Publishers Who Lunch: The Social Networking of American Book Publishers” (2015), we are reminded that in the first half of the 20th century, most of the big trade publishing houses were located in New York City—midtown Manhattan to be exact. And that this proximity between houses led to active socializing between publishing executives, gathering over two-martini lunches at restaurants and clubs. These gatherings, the analog version of social networking, became the impetus for the founding of the Publisher’s Lunch Club (PLC) in 1915. PLC was an informal yet influential organization where to be a member, you had to be elected, and to be elected you had to be “a partner, director, officer” of any U.S. house publishing copyrighted books. Such criteria meant that members were WASPs educated at Ivy League schools, and that many of its leading members represented “multigenerational, family-owned firms bearing the family name or names”:

… [who] considered themselves the cream of the most highly regarded and culturally valuable in the publishing industry, a judgment that others in the trade acknowledged. Their professional identity marked them as creators of culture and perpetrators of civilization.

This “creators of culture and perpetrators of civilization” syndrome from a hundred years ago reminds me of our current fascination with the influencer, steadily morphing into a grisly cyborg from the black lagoon of TikTok. Yes, it aims to suck all the independent thinking out of you. (As of 1:25 p.m., January 19, it looks like TikTok will be allowed to continue.)

The paradigm that economist Max Hall termed the “Manhattan luncheon table as the provider of ideas” has become the publishing phenomenon of “basically white people looking for books about white people about white people.” (As quoted by an agent in a 2022 New York Times article.)

As evidence, I offer up my book collection from tweenhood. Most of the titles came from the long-gone flagship Barnes & Noble store, once located at 18th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. My mother took me there to shop for books almost every weekend when I was in junior high. Most of the books’ authors were white and they wrote mostly about white people. Apparently, I was a big fan of Beverly Cleary YA novels judging by my cache. Most notably Fifteen, which depicts first love in a small town. But reading this book in 1981 is not the same as reading it in 2025. The problematic moments manifested by the author’s desire to add details to offer readers authentic experiences is off-the-mark and offensive, as she does it in a way that “others” another culture. When Jane Purdy, the fifteen in question, is going to eat dinner at a Chinese restaurant with the “new boy in town” and some friends, she encounters food she has not tried before: “She was beginning to remember that the Chinese ate some strange things.” Not to mention this comment from an adjacent character: “I know what,” said Buzz. “Let’s have flied lice.”

In the journal Social Theory and Practice, Professor of Philosophy Brynn F. Welch writes that the pervasive whiteness of children’s books “contributes to the notion that white is the norm or default while other races are variations from that norm. Setting white as the default skin color contributes to the common reduction of characters of color to one-dimensional figures.” Cleary wrote Fifteen in the 1950s when pursuing and abiding stereotypes of non-whites was just a foregone conclusion.

When we allow others to write our story, we remain invisible.

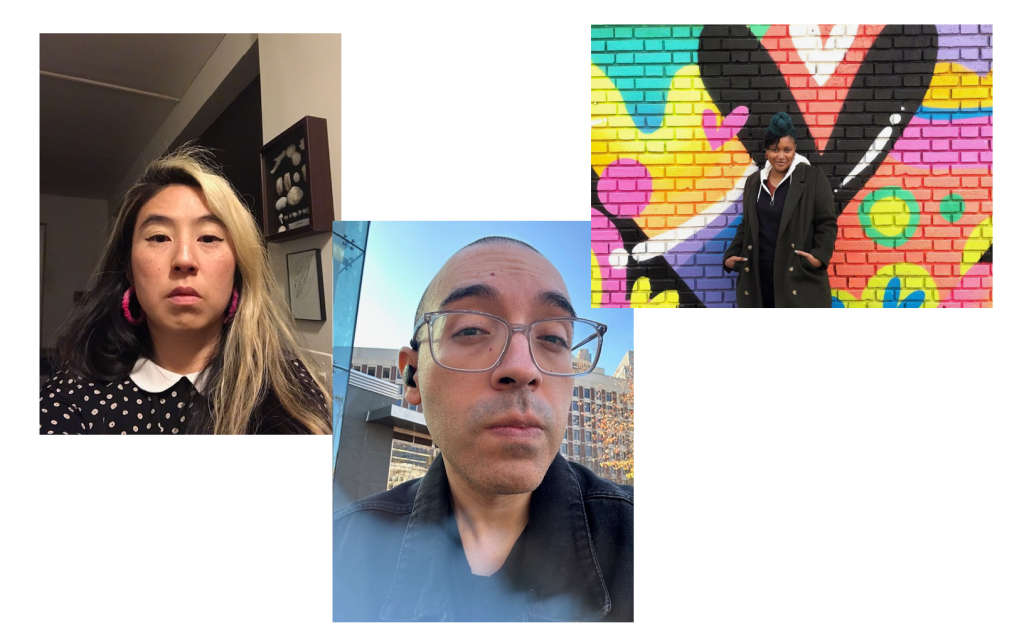

I became a Co-Editor of a small independent press around 2021. I am the first and sole editor of color at this press. I didn’t think about this much until after I attended an online meeting for editors of color back in 2023, hosted by the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP). I think we might have discussed challenging submissions and our “editorial practice” at this meeting, but my main takeaway was that being an editor of color was an issue in itself. In order to organize my thoughts and gain perspective, I reached out to two editors who were also at the meeting, NaBeela Washington and José Angel Araguz.

Washington, Editor at Lucky Jefferson, feels the weight of representing such a small percentile, but is clear on what it means to be an editor of color:

Representing such a small percentage, industry-wide, has been (and is) such a tough pill to swallow. It makes the work at large seem so much more daunting; and that can feel incredibly isolating. After a while I start to think “how” or “why would they listen to me.” I am constantly remembering that oppression outnumbers me.

I’ve been telling people a lot lately that they shouldn’t just become an editor for the sake of camaraderie, they should become one if they have the strength to do what it takes to see the old ways of thinking and doing things crumble.

Araguz, Editor-in-Chief at Salamander, also understands the isolation and impact of his role:

One of the things I looked forward to about taking the position as Editor-in-Chief is the possibility of being one of a few editors of color in our field. Taking this position on in a way that reflects my authenticity and values has been a struggle. I have had to educate staff and others in real time as to why I would want to be more inclusive in everything from our social media presence to what we publish and how it gets selected.

The magazine itself had been around 20-plus years, embedded in the Boston literary scene which is often unwelcoming to outsiders. Outsiders, in their definition, I have learned is anyone marginalized and not from here originally. There’s a strong mix of clout chasing and performative inclusion, a symptom of capitalism and its bottom line as well as the fairly white nature of the publishing business in general, that makes Boston an often isolating experience for a writer of color.

I’m glad that Araguz introduced this idea of the “outsider”—a figure who represents our struggle to be seen and acknowledged in publishing as peers, as equals. Though this outsider status in an industry that has staunchly maintained its roots in whiteness is both disheartening and tiring, the flip side of the coin is that it has also served as an impetus to make sure our presence stays and grows in the landscape of publishing. It is this sense of responsibility that resonates with both editors as they embrace the advocacy and activism aspects of their role. Washington writes:

My responsibility is to develop and examine editing philosophies that diminish gatekeeping; to publish and collaborate with artists and writers from communities we serve, that are historically underrepresented; to steward, create, and adapt spaces that foster creative engagement, and look for equitable solutions to problems impacting the industry; to implement solutions that are purposeful and designed to reform the status quo.

Editors should be prepared to question and confront traditional methods of publishing. This might include challenging the reliance on print media as the primary mode of dissemination, questioning the exclusivity of traditional publishing houses, and exploring new avenues for content distribution such as digital platforms and self-publishing.

Araguz adds:

To the question of what the responsibility of an editor of color is in a position like ours, I would say that along with the duties that come with the job—copy editing, reading, doing layout, et cetera—you also have to be a sensitivity reader, an educator like I mentioned above, and in general a curator of intersectional spaces and best practices. For example, when it comes to selecting art for art features, I make sure to intentionally select artists from underrepresented backgrounds. I also do things like make sure to read every cover letter and ask my readers to make note of anybody who identifies in their cover letter as coming from an underrepresented community, so that when it’s forwarded to me, I can set the intention and follow through giving specific extra attention to them.

I feel like my responsibility is to save people time, stress, and grief that is unnecessary. And there’s so much of that in the writing world. And there is so much money to be made off of people’s anxieties and lack of knowledge around writing in the writing world. And I just want to share the tools, connect with people and have them able to access their authentic selves through words.

Certainly, systems and traditions that keep and defend the status quo to hold on to power and a superiority of position must be questioned and challenged to change.

Washington understands that the first step is to start looking at the “editing philosophies that diminish gatekeeping” so that opportunities and platforms are extended to artists and writers from historically underrepresented communities. This situation is how “the old ways of thinking and doing things crumble.” And when Araguz describes a system where making money from “people’s anxieties and lack of knowledge around writing in the writing world” is tolerated, perhaps even elevated, we know that there is rot at the root. The real work of publishing must focus on stewarding and adapting spaces to foster creative engagement so that, as Araguz puts it, we are connecting with people while helping them “access their authentic selves through words.”

Ultimately, the impact of change on an industry that has for so long turned its back on the rich diversity of this country’s people will have to come from these very same people. The people of underserved and misrepresented communities who understood all the while that stories of their “authentic selves” must also be acknowledged and shared in our public discourse.

Araguz’s commitment to community building comes from his experience with “bad mentoring” and wanting to make sure he breaks the cycle by holding the door open for people, not closing it:

When I think about the different communities that I am lucky enough to have built and engage with, I think back to a bad mentor that I had from undergrad. A couple of years after graduating, years of small journal publications and finding my way, they told me that I needed to go out more. That I needed to go to more readings and get to know more writers. This was after the MFA as well. The MFA which left me rather scared of writers, unable to pick up a copy of American Poetry Review or even Poets & Writers magazine, because there were all the people who looked at me sideways during the MFA, winning awards and getting published. I also felt like my mentor didn’t see me. This was right when writers were beginning to be more and more on social media, more writers, journals, and presses on there, more accessible spaces for an introverted, neurodivergent writer like myself. I have been burnt more than once when trying to approach writers in person. One even looked mad that I introduced myself without having bought his book. And I just never feel comfortable doing so. But retweeting the latest publication of a favorite writer or doing a review of a writer that I admire and posting it on my blog, that feels accessible.

Both editors believe in the new generation of writers and editors to really make an impact by building connections through generations and taking on the role of “agents of change.” Araguz shares:

I think there’s a lot of possibility to be explored in the direction of shepherding the next generation of writers. I think there’s a lot we can learn from younger writers in terms of social media and its developing role in people’s lives. It doesn’t mean that the journal or press has to compromise ideals and values in order to meet and chase after a capitalist bottom line. Shepherding writers also through the pages of journals and anthologies and in the catalog of presses, helping to make connections across generations and cultures through the writers published, and in general helping foster community locally and nationally, and globally, why not, that’s the work we might be able to do and put our shoulder too.

Similarly, Washington offers:

New editors should question their role as agents of change by actively challenging the status quo in publishing. This could involve advocating for the incorporation of technology in publishing processes, embracing diverse voices and perspectives that may have been harmed or marginalized in traditional publishing, and promoting environmentally sustainable alternatives to traditional printing.

Like creating free and open submission platforms: establishing or advocating for writers from all backgrounds and reducing the reliance on exclusive literary circles or established connections; dedicated mentorship programs, fee-free literary prizes and contests for emerging voices, and outreach efforts to discover talent beyond conventional channels.

I really think that if you build something intentionally, your community will find you; the people who believe in your vision will come out of the shadows to support you and together you’ll grow to sustain something magical.

A Black journalist, poet, organizer, and connoisseur of croissants, NaBeela Washington (she/her) writes about what’s possible. She holds a Master’s in Creative Writing and English from Southern New Hampshire University and is the proud mama of arts publisher Lucky Jefferson. She’s working on research revealing how incarceration psychologically impacts civic engagement and a children’s book. Check out her words in The Cincinnati Review, Roanoke Review, Crazyhorse, The TRiiBE, Chicago Reader, and others.

José Angel Araguz, Ph.D., is the author most recently of the lyric memoir Ruin & Want (Sundress Publications) as well as the poetry collections Rotura (Black Lawrence Press) and La esperanza espera (Valparaiso Ediciones). His poetry and prose have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Poetry International, The Acentos Review, and Oxidant | Engine among other places. He is an Assistant Professor at Suffolk University where he serves as Editor-in-Chief of Salamander and is also a faculty member of the Solstice Low-Residency MFA Program. He blogs and reviews books at The Influence.

Jiwon Choi is the author of One Daughter is Worth Ten Sons and I Used To Be Korean.

Choi’s third book, A Temporary Dwelling, was published by Spuyten Duyvil in June

2024. Her work can be found on Mom Egg Review, Painted Bride Quarterly and Heavy

Feather Review. She started her community garden’s first poetry reading series, Poets

Read in the Garden, to support local poets. You can find out more about her at iusedtobekorean.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.