During the pandemic, it was commonplace to hear people talk about how slippery time is. The lockdown dramatized the strange and sinuous qualities of time, the ways that time can stall and slip off the surface of consciousness all at once. These properties of time are difficult to capture, although many poets have tried. Whish is one of the first collections that I have read that does so with side-splitting humor and a distinctively playful imagination.

Whish, Jackie Craven’s second collection of poetry, explores time’s quirks, its discontinuities and quantum nature in a series of prose poems. Deep Time, hospital time (limping and inward), human time, capitalist time: all are explored in Whish with a sly intelligence that revels in the temporality of lyric poetry with its invitation to slow down and pay attention, to think and feel outside of the demands of the attention economy. Winner of the Press 53 Award for Poetry, Whish is steeped in magical realism and personifies time; as much as it is an ontological, time, in Craven’s hands, is also a wayward phenomenon, subject to critique in the context of industrial time: “Management has hired three new seconds but they mangle every task.” The “Human Clock” appears regularly throughout the collection, reminding us of the constructedness of Western perspectives of linear time. In personifying time, Cravens turns it into a surreal and whimsical figure, straining against her own limits: “Alone in her room, the Human Clock chitters and hums. Walls vibrate with gnashing gears, each one sharp as a baby’s tooth. Half girl, half machine, she eats shadows in bed … I want to crack her door and touch the edge of her secrets.”

Endowed with agency, time is malleable, contingent: in one poem, it is “jolt[ing] awake” (6), while in another, it’s “working on a novel.” It is—above all—queer, subverting the temporal march of progress that often occurs at the expense of the socially marginal. In the domain of queer time, objects and people become subjects with their own behaviors that disrupt the clockpace of the neoliberal state where the capitalist dynamics of time are supreme. In Craven’s hands, time falters, enabling us to experience a novel structure of time and identity: “The red line rumbles at the gateway station and luggage refuses to board …. Name tags loop around buckles—pocket watches escape rattling their heavy chains. Brazil and Haiti run away. Entire continents vanish into the crowd.” Particularly exciting are the ways that Craven disrupts the temporality of the state, while making deeper ontological connections across temporal vistas.

But human time is finite, particularly commodified time, and Whish is nothing if not a collection of longing for more time: “What if half past yesterday returns, giddy as a lottery ticket. What if the prodigal hour tumbles in a gale, hops from a tree, lands on an ephemera table at the flea market in Liberty Park … I grope my pockets, ready to pay all I have.” There are elegies that toy with time (or anti-elegies in the case of a dead ex-husband), that ache for a father, mother and sister who have passed. “Just for once, I want to witness / the going away. I want to catch the moment, / cup it in my hands, see it blink like an altar candle. But in this dream, the Red Line shrieks from the terminal / hours before I arrive. Or I reach Port Canaveral / after the Botswain’s final call.” Time, intangible but pervasive, is refigured constantly in Craven’s hands; it can be embodied, even visceral, or mysterious and nonhuman as in her figurations of Deep Time. With a marvelous metaphorical imagination, Craven reminds us that in the process of living, we often forget that time is a paradigm ripe for deconstruction and re-imagining. Under the dominion of neoliberal time, we may need reminders, such as those in Craven’s writing, that we can resist its injunctions and capitalistic framework. Poetry, which can slow down time and invite us to live for a while outside of the temporality of the market economy, seems especially well-suited to facilitate this resistance.

Dreamy, with an imagination dynamized by a magical realist sensibility, Craven’s collection imagines past, present, and future as wily characters that intervene and trouble, shape and undermine our best intentions. You’ll find Nancy Drew in these pages, allusions to Einstein and references to Star Trek, as well as list poems, typographically playful poems, and beguiling titles like, “Long Before Periwinkles Appear, I Hoe My Life into Tidy Rows.” Always in Whish there is a spirit of play and an interest in renovating and re-conceiving worn conceptions of time.

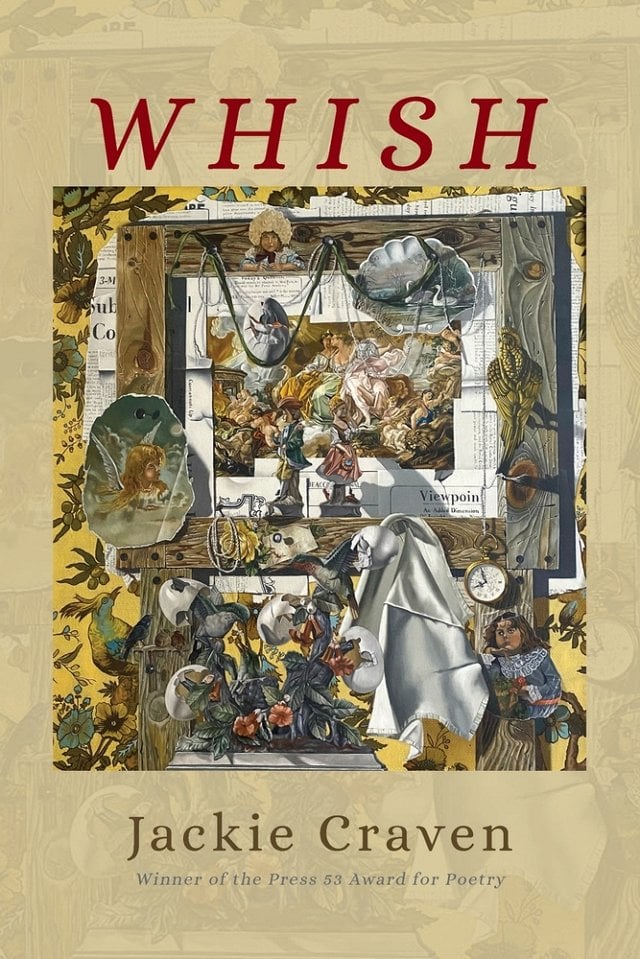

Whish, by Jackie Craven. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Press 53, April 2024. 84 pages. $17.95, paper.

Sarah Giragosian is the author of the poetry collections Queer Fish, a winner of the American Poetry Journal Book Prize (Dream Horse Press, 2017), and The Death Spiral (Black Lawrence Press, 2020). In 2023, the University of Akron Press published the craft anthology Marbles on the Floor: How to Assemble a Book of Poems, which she co-edited. In 2024, Middle Creek Press released Mother Octopus, a co-winner of the Halcyon Prize. She teaches at the University at Albany-SUNY.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.