By the middle of her poem “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” Caribbean Canadian poet M. NourbeSe Philip has worked “English” from a “mother tongue” to a “father tongue” to “a foreign anguish” by rubbing it against what “mother tongues” and “father tongues” mean in relief of slavery-era edicts bent on the “removal of tongue[s].” Both “Discourse on the Logic of Language” and the collection that houses it, She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, are bothered by the anguish of living with(in) a language that seems intentionally designed to keep one out. Philip states, in the collection’s introductory essay, the “success” of any creative writing “depends to a large degree on the essential tension between the i-mage and word or words giving voice to the i-mage.”

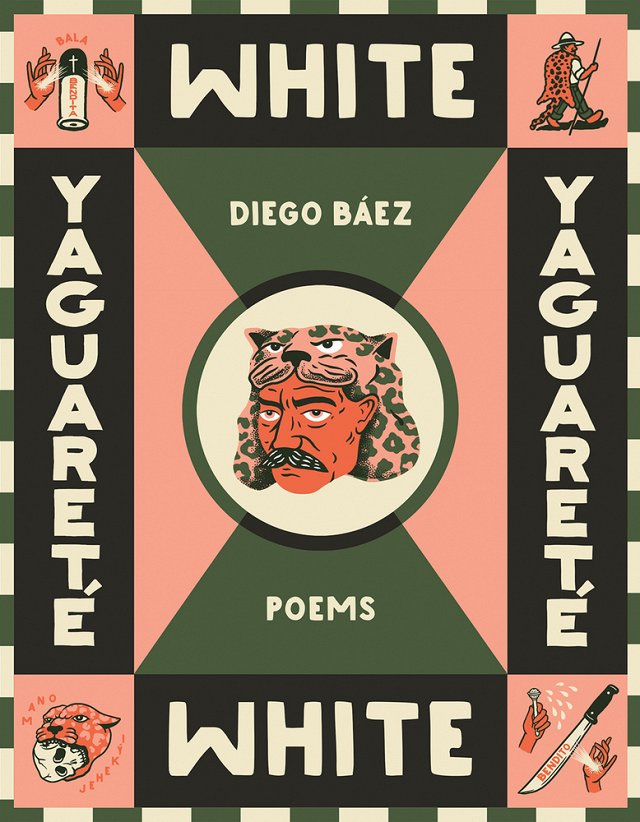

The resounding success of Diego Báez’s debut poetry collection, Yaguareté White, directly relates to the fact that each individual poem and the collection as a whole seem to be created out of Philip’s tension—the tension between the poem and the very language(s) in which it is written. Although unlike Philip’s poems, Báez’s tensions are not only about language designed to keep one out, but about how to write (or live) in languages one doesn’t know, or how to write (or live) in cultures that are far from the popularly known and often misrepresented. In the collection, Báez masterfully creates a true mosaic out of poems that meditate on the tension of what it means to live both in, of, and outside of at least three different languages (English, Spanish, and Guariní) and two (white American and Paraguayan) distinct cultures.

Báez grew up in central Illinois as the son of a white mother from Pennsylvania and a Paraguayan father. He grew up not learning Spanish as a kid and with no Spanish-language community nearby. Yet, throughout his childhood, Báez would take month-long trips to visit and stay with family in Paraguay, being immersed not only in Paraguayan culture, but in the multilingual language community of Spanish, Guaraní (the pre-Spanish language of the indigenous community of the region), and Jopara (“like Paraguayan Spanglish) that made up his extended family. Báez did all of this “speak[ing] none of the above.” The obvious tension between being disconnected through language and connected through blood seems to be both the genesis for Yaguareté White and the invitation of engagement offered by Báez’s poems.

Working through three sections, Báez alternates between poems that explore the speaker’s experiences, poems about the American (lack of) understanding of Paraguay, poems about the Guaraní language, and poems about Paraguayan history. There is a through-arc not so much of revelation, epiphany or revolution, but of an understanding that the question and vibrating tension is unresolvable, forever, and an inheritance now passed down to the speaker’s daughter, as he writes in the final poem, “Portrait of an Artist with Clubfoot”:

like a toddler or palmoa, braces on my feet

the moment I entered this English-speaking

world. And you, my child, how will you move

past the past and through all of your fathers?

on py broken by chance and blood?

or nandi and longing as the day you were born?

The alternation between English and Guaraní (palmoa: pigeon; py: feet; nandi: empty) and the developed metaphor that makes analogous being born into an exclusively English-speaking community and being born hobbled are indicative of Báez’s work. At their best, Báez’s poems ring with the dislocation and confusion of trying to understand a world that seems to be labeled (and to label) in a language that excludes the parts of you and your loved ones that you wish to understand most. This dislocation (although, sometimes, location) most often plays out in the poems about the speaker’s father, moving them past run-of-the mill father and son poems and into a realm very specific and particular to the collection’s speaker. The back-to-back poems “Regalito” and “Lengua” in the first section are prime examples of not only Báez’s father and son poems, but in how well one poem in the collection overlaps with the next. In “Regalito,” which is Guaraní for gift, Báez writes in couplets about “why [my father] didn’t teach us Spanish,” ending with the father’s beautifully elliptical and ironic line: “ ‘There’s not a word for that.’” Báez follows “Regalito” with “Lengua” a prose poem that plays off of the multiple meanings of “lengua,”which is Guaraní for tongue, and in the poem means both a food “loved by my father” and “a word for language.” It is not hard to make the jump from the end of “Regalito” straight into the heart of “Lengua,” and this ease of movement from poem to poem is a hallmark of Yaguareté White.

The skill of Báez’s intention and word play both in the poems and in the order of the poems makes reading the collection (and rereading the collection) from cover to cover necessary and wildly fulfilling. The individual poems are filled with what Edouard Glissant might call particulars—anything from the anti/ante-lingual bonding of cousins who don’t share a language to having to search up the history of your relatives online to the fact that there are no more jaguars (yaguaretés) left in Paraguay—that only reveal their full nature and give their true gift in relation to the other particulars, all successfully humming with Philip’s tension of language and image.

Yaguareté White, by Diego Báez. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, February 2024. 112 pages. $18.00, paper.

Dan Hodgson is a writer and teacher based in a fertile river valley.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.