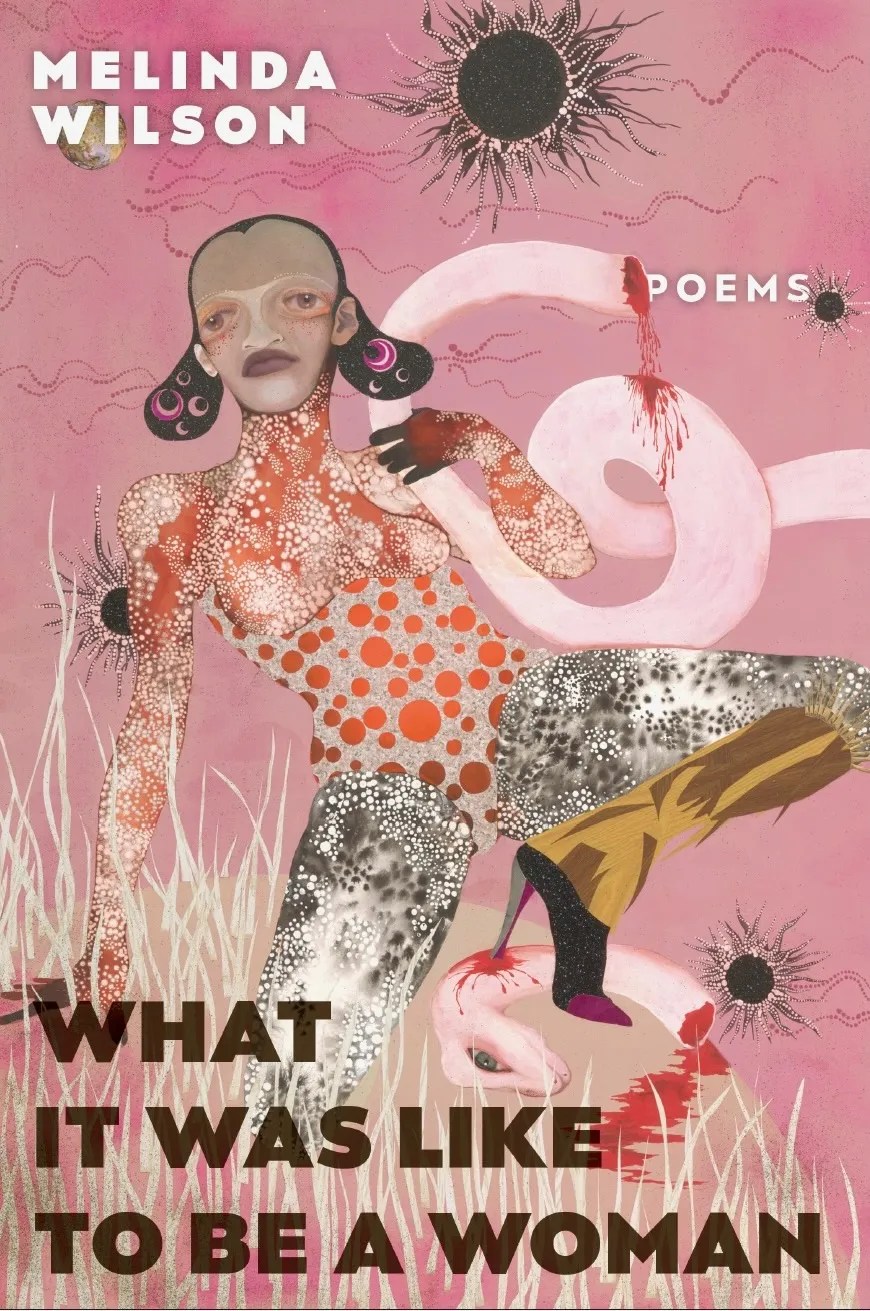

Melinda Wilson’s heroically tough and vulnerable book, What It Was Like to Be a Woman, relays this very information with grit and beauty. From childhood through to the present, Wilson’s poems illustrate that under patriarchy our bodies are never our own, and the struggle to keep what’s ours ours—mind and body—is one that spans a lifetime. Throughout, however, the poet reminds us of the revelation in the everyday, and the grace found in the struggle. —Lynn Melnick

Sylvan Missive

Even a defeated hornbill Pragmatic procreation And after all that,honeydew We learn patience Everyone can be redeemed Its new growth

outstretched

to the cowering wolf pups because forests find their way back after disaster.

Hibernaculum We wonder if I am the world’s Now available from Indolent Books Melinda Wilson is the author of Amplexus, a chapbook from Dancing Girl Press. Her work has appeared in Verse Daily, The Cincinnati Review, The Minnesota Review, The Wisconsin Review, Evening Street Review, Arsenic Lobster, Diner, Maryland Literary Review and many other journals. She is a founding editor of Coldfront Magazine, and she is the Director of the Center for Academic Success and faculty at Manhattan College. She lives in Bronx, New York. Reprinted with permission of Indolent Books Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

is useful in the system

of the forest,

the passing of figs

from bill to bill

and the winged spreadof seed.

is an automatic beauty.

turning out to have been

excrement

all this god damn beautiful time.

when the mating tree

is occupied

and leave

our calling card sweet with perfume.

in this dystopia.

Even Chernobyl

coaxed an ecosystem

back from the great grave.

to the not-yet-rabid raccoon dogs

largest nocturnal primate, while

the awful acid of my electric

heaves and the semi-rhythmic

creeps of my grief pickle my organs.

But I am not a harbinger of evil

like the aye-aye. Native superstition

requires the lemurs to be killed on sight,

for they are rumored to sneak

through a thatched roof and puncture

an aorta with a thin middle finger.

Villagers hang them by their feet,

their bony fingers curled tight toward

the ground. I stare at the images for hours,

imagine their faces pinched with suffering.

And when I see a dead calf on I-10,

you put your hand on my leg,

but you do not presume to know

the particulars of my perennial ache.

So we focus on a moment’s sun, and

at night, the smoke white of leafy

sea dragons threaded into the skyline.

Paradise always retreats. The lakes

and the ponds of the city’s parks freeze,

and we are winter frogs, spring peepers

slowing our living to small measures

of death. We recess in crevices of alpine

rocks, we say it won’t be long

before the air is humming again.