In Mountain Time: A Field Guide to Astonishment, Renata Golden challenges assumptions about both the natural world and well-known human histories. She begins her essay collection by weaving together the narratives of her ancestors, Irish immigrants who came to the United States after the Potato Famine (to which Golden refers as An Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger), and the indigenous ancestors of and to the land on which she now lives, the Apache people, more specifically the Chiricahua Apache people. Golden frequently refers to herself throughout the collection as a kind of double interloper; she separates herself from both the Chiricahua Apaches and the white settlers who have been living on the land for hundreds of years. I appreciate this recognition Golden does; it never feels forced or apologetic for its own sake, but rather serves to continually remind us (and maybe also herself) that this land on which she has made her home had many claims on it well before she arrived. “I, too, am a tenant,” Golden writes, “merely borrowing space here for the time that I exist on this earth, aware that my footsteps aren’t the first on this land.” This simple, straightforward acknowledgment sets a strong tone for Golden’s essays: she deeply loves and enjoys the land on which she has found herself thanks to various historical accidents and she simultaneously lays no claim upon it; the ease with which she holds her relationship to the land of the Chiricahua Mountains is admirable.

Starting early in Mountain Time, Golden writes about growing up on the South Side of Chicago, where I live now, another part of the United States that famously, sensationally, has had many claims laid upon it. The land now known as Chicago was originally home to three Anishinaabe tribes, known collectively as the Council of the Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes. This council stewarded the land of the Great Lakes region starting around 800 CE. Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, known as the first permanent settler of Chicago and founder of the city, was a Black Caribbean man from Hispaniola who married a Potawatomi woman and built a farm at the mouth of the Chicago River in 1788. The South Side of Chicago has been a locus in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries of American anxiety about gun violence, gang violence, and racial tensions, especially for Americans who do not live here. Overwhelmingly populated by Black Americans whose ancestors came to Chicago during the Great Migration, many of the neighborhoods that comprise the South Side have historically been disenfranchised and under-resourced. Golden does not explicitly draw specific parallels between the South Side of Chicago and where she currently lives, but the overall parallel feels deliberate and well-employed.

Golden also discusses the American-Mexican border at length, and the movement, or attempted movement, of people across it. “[S]tatistics challenged me to consider the great hunger that sets a group of people on the move—a hunger for a better life and safety for themselves and their families,” she writes. “The craving for an opportunity, however small, to feel your dreams are not dreamt in vain. Security measured by the incremental removal of negatives, like fewer death threats, less chance of gang violence, reduced degrees of desperation. The too-heavy burden of hope carried by the people who died here.” This alignment of migration across the southwestern American border with migration of the Irish because of An Gorta Mór,using word “hunger” in both the literal and figurative senses, is another elegantly executed parallel of Mountain Time.

Formally, the last chapter of Mountain Time, “A Chiricahua Glossary,” offers the most striking example of Golden’s ability to synthesize the landscape and culture in which she now lives. The glossary definitions range from single words to paragraphs, and from quite literal to more poetic. Some of my favorites are “Border. Delineate, dream, deny, exclude, entrap, in that order,” “Dust. Everywhere,” “Extirpation. Often confused with extinction. Extirpation means that a species no longer exists at the local level. Extinction means the species no longer exists anywhere. If your favorite animal […] has been extirpated from your area, you can hope that a zoo somewhere in the world has developed a program to try to save the species,” and “Parthenogenesis. Reproduction that does not require sex. A real-life form of virgin birth. There are as many types of parthenogenesis as there are sexual positions, but most types involve females who produce clones. Practiced locally by whiptail lizards.” The definitions that comprise this glossary are by turns sincere and tongue-in-cheek, scientifically precise and lyrically expansive. By giving herself a significant formal restraint in this essay, Golden produces the most resonant summaries of her themes.

I have read a fair amount in the genre I would classify as “essay collections in which women tenderly observe nature and critically observe the human systems that have shaped it,” particularly in the last few years, and Mountain Time holds up to some of my favorites. Those include Laura Marris’ The Age of Loneliness (2024), Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (2013), Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing (2019), and Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974). All these books have and accomplish different goals, including Mountain Time, and Renata Golden offers a strong addition to the canon.

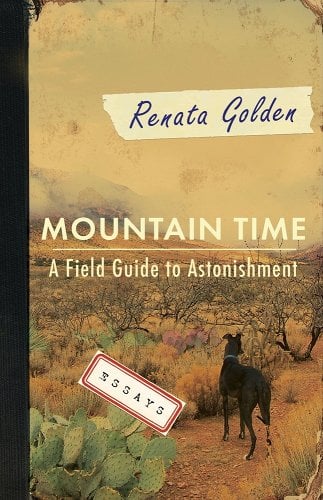

Mountain Time: A Field Guide to Astonishment, by Renata Golden. Columbus, Georgia: Columbus State University, March 2024. 196 pages. $21.79, paper.

Annie Diamond is an Ashkenazi Jewish poet and recovering academic who has made her home in Chicago. She has been awarded fellowships by MacDowell, Luminarts Cultural Foundation, The Lighthouse Works, and Boston University, where she earned her MFA in 2018. Her writing has also been supported by the Indiana University Writers’ Conference, Ox-Bow School of Art, and the Ragdale Foundation. Her poems appear and are forthcoming in Western Humanities Review, No Tokens Journal, Sonora Review, and elsewhere.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.