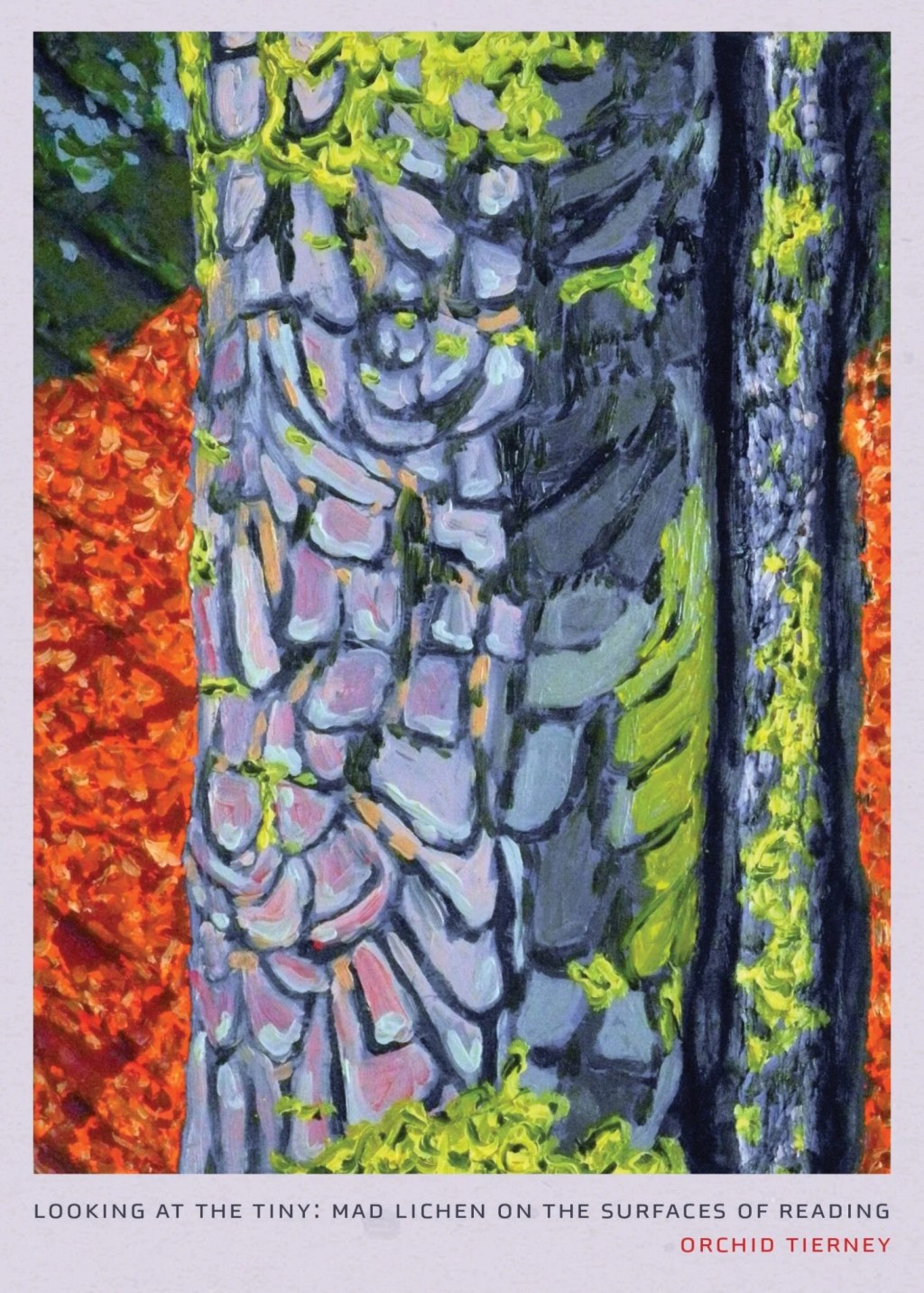

Orchid Tierney’s beautifully composed essay looking at the Tiny: Mad lichen on the surfaces of reading is like a musical piece that takes a handful of motifs from a previously existing work and resets them, interweaves them, varies them, and develops them into something new and distinctly its own. For Tierney the previously existing work is Lew Welch’s poem “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen.”

Like his friend Gary Snyder, Welch (1926-1971) was a poet associated with the West Coast Beats who drew inspiration from the natural environment of the Western United States. “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen” appears to be one of the last poems Welch wrote; it tells of his epiphany on noticing, really noticing for the first time, those small hybrid colonies of algae and fungus that grow on the surfaces of rocks, treetrunks, leaves, and virtually anything else. “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen” is Welch at his best. It shows him to be a close observer of the contingent details of the landscape surrounding him, which he encounters in a spirit of what Jonah Raskin described as “intense mindfulness.” It is the same spirit that animates Tierney’s insightful engagement with his work and with her own meditations on the inextricable, and at the same time tension-ridden, entanglement of the natural and human worlds.

looking at the Tiny is written in two different, but mutually supporting, registers: the footnoted, scholarly essay, and the poetic meditation. In the first register Tierney draws on Welch’s poetry, prose, and correspondence as well as on the scientific literature on lichens, in order to set out the objective contexts in which Welch’s poem can be read—from the outside, as it were. In the second register she gives us her own subjective engagement with Welch’s poem—a close reading from the inside.

The central subject through which Tierney explores Welch’s poem as well as her own experiences is the polymorphic, surprisingly complex thing that is lichen. Polymorphic, but unique nevertheless: at the beginning of her essay Tierney writes that

lichens cannot be likened since they’re unlike anything else. indeed lichens are their own culture-making depositories of strange life … and what can I say of this marvellous plural thing, this beautiful, blotchy multi-colour not-animal-not-plant-more-than-human warehouse? … lichens are their own empire, their own fantastic kingdom of small likeness.

Her plays on the words “lichen,” “like,” and “likeness” set up conceptual as well as sonic rhymes that hint at the range of meanings that these small organic growths will take on as she reads them through Welch’s poem and life, and then sees them intimately on her own. There is lichen as bioentity; lichen as a metaphor for the ability of the microcosm to contain multitudes; lichen as a symbol of the symbiotic relationships binding unlike, and perhaps even contradictory, things together in complex wholes; lichens as revelatory of the limits of the human mind; and even lichens as the guarantors of the continuance of the ecological lifecycle. For Tierney, lichens exemplify Donna Caraway’s concept of “natureculture”: the synthesis of the nonhuman and the human domains. Carrying these various associations, lichens appear and reappear throughout the essay, providing the foundation for the secondary themes and variations Tierney introduces and elaborates on top of them.

One of these themes is the disciplined practice of observation: the necessity of engaging in a thoughtfully receptive encounter with natural phenomena. Tierney emphasizes that paying close attention to the world and its details is the central thought animating “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen” as well as Welch’s poetics in general. She deftly draws a connection between “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen” and Welch’s earlier poem “Philosophy,” from his 1968 collection Courses. She takes the final line of the earlier poem’s first stanza—“observe, connect, do”—as a motto encapsulating the ethos underlying Welch’s later poem. It is the ideal to be realized in practice. On her reading, this ideal finds expression in the mindful observer whose observations are made in a spirit of participation with the observed. Rather than a Cartesian subject contemplating an ontologically alien object, this observer is one who recognizes that observer and observed are co-implicated beings who happen to be sharing the privilege of being within a larger home. It is an ethos Tierney opposes to the systems and institutions of industrial and postindustrial societies, systems she sees as hampering human creativity and obstructing our ability to grasp the connections between the world’s human and non-human domains. She suggests that, following Welch’s example, by looking at the overlooked, the ostensibly insignificant, and the small-scaled we can, with an empathetic eye, perceive these connections and comprehend that there is a point at which the contradiction between the two domains disappears. Hence she writes that Welch’s poem

collapses the cosmological and temporal scales of the mountainous environment. it implodes and human and the wilderness, the urban and rural spheres. natureculture.

Properly observed, the lichen is the small entity whose embodiment of symbiosis is the sign of a state in which the microcosm stands for the macrocosm: as with the small, so with the great.

Appropriately, looking at the Tiny ends with Tierney’s own looking at these tiny beings. She writes of her close encounter with the lichens she finds during a walk in Nebraska’s Riverview Nature Park with the artist Maya Strauss. Her attempts to identify exactly which lichens she saw notwithstanding, she concludes that

what really mattered was that I had observed them on the logs, branches, and tree trunks … wasn’t that enough? I had seen them. this lichen!

looking at the Tiny: Mad lichen on the surfaces of reading, by Orchid Tierney. Buffalo, New York: Essay Press, 2023. 27 pages. $12.00, chapbook.

Daniel Barbiero is a double bassist, composer, and writer in the Washington, DC area. He writes on the art, music, and literature of the classic avant-gardes of the 20th century, and on contemporary work, and is the author of the essay collection As Within, So Without (Arteidolia Press, 2021). Website: danielbarbiero.wordpress.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.