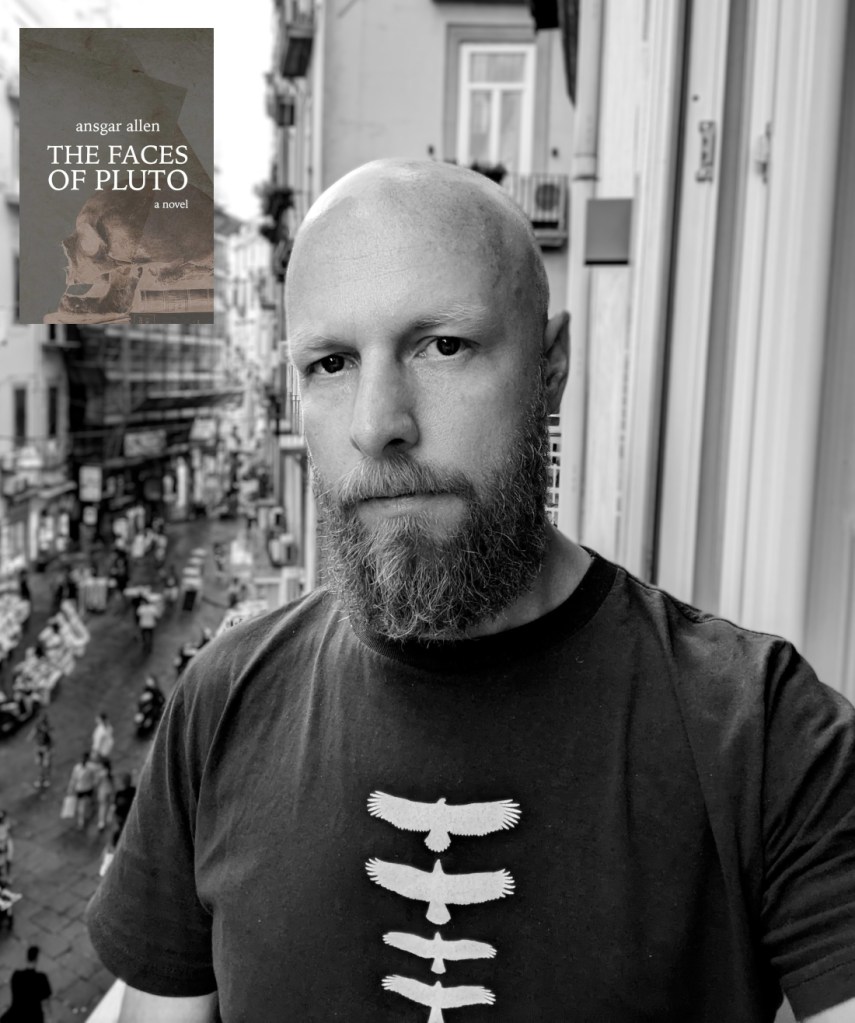

Ansgar Allen’s fictions roam like ruminants in search of fertile land from which to graze. Over the course of seven novels, Allen has traveled in nearly as many directions in terms of both style and substance. His latest, The Faces of Pluto, is perhaps his most inscrutable book to date. A dense whirlwind of interrogations and allusions, the novel follows a narrator exploring an unknown land, cut in with text from some of history’s most dedicated falsifiers and the narrator’s commentary on said texts. As the novel progresses, the source texts and the narrator’s responses begin to blur together to the point that it is unclear who is falsifying what and to what end. To say that this places the reader on unsteady ground would be an understatement—it is both exhilarating and frustrating, which I suspect is what Allen intended. Although Allen sees bleak prospects for the technology of “the book” and its attendant activities of reading and writing, he also relishes the paradoxical opportunity to both elevate and eviscerate their value from within the confines of yet another book. We discussed these prospects and paradoxes, and other aspects of his work, over email in November/December 2024.

S. D. Stewart: The Faces of Pluto is a departure in style from your previous novels (though closer to your earlier nonfiction works Benign Violence and The Cynical Educator), and yet, theme-wise, it feels like a familiar but more deliberate interrogation of the actions of reading and writing, and the concept of the book. Beyond that, it is even more brazen in its efforts to destabilize the reader. In your 2023 interview on the Unsound Methods podcast (transcribed at minor literature[s]), you mention being drawn to “the productive absurdity of a situation where a book makes claims against books, where a book takes aim at some of the ideas that make book writing possible, and then undermines those claims by encasing them within another such object.” Do you consider The Faces of Pluto to be such a situation, and how do you feel that the book fits into your corpus to date? Do you see it as an evolution, or are you disinclined to think of your fictive works as building from one to the next?

Ansgar Allen: Yes, to some extent The Faces of Pluto manifests this absurd predicament; it intuits the end of books and does so within the space of a book. Writing it provided an opportunity to reflect again, but differently, upon the situation of living in the last days of the book, not merely in the sense that the traditional book (as codex) is an exhausted form, but in the more dismal sense that I fail to imagine a future that will give sufficient numbers of people sufficient repose to indulge themselves in an artefact that requires time, and a degree of comfort, if it is to be appreciated and not merely glanced at.

There are other, seemingly paradoxical effects of living in this predicament. As an antiquated technology, the book does offer its own opportunities to resist a present that has no time for it. Books are worth returning to because of their coming obsolescence. They isolate and bewilder readers, they fail to sufficiently entertain, they do not sufficiently entrance. They frustrate.

And as a technology on the way out and approaching obsolescence, the book does offer those who still indulge the activity of writing them, certain encouragements. In particular, for writers, there is now the freedom of not having to worry at all if what they write will stand the test of time. Writers need not give much of a thought to how they might be read by a future readership. They need not even worry if the book they are writing will grace their present. If there is no real prospect of a future in which humanity will have sufficient comforts to sit back and savour these books we might currently be writing, these concerns are no longer so relevant. The activity of writing can become much more immediate, and each book may be allowed to be a necessary experiment and, perhaps, an almost immediate failure. This may be why I am prepared to produce books at whatever pace feels necessary to my own efforts to think, rather than, say, ration these books I write in order to maximise their impact. This does not mean that I do not anguish over minutiae, as if they mattered. Because I do. I find the final moments before approving a set of proofs to be painful. I am reduced, at last, to deciding for one word against another very similar word, or this punctuation mark for a nearly identical arrangement. These final indecisions tend towards dementia, and the end of the book, its death for me, has already happened long before it is printed.

As for my fictions and nonfictions, you’re right, I don’t see them as particularly divergent, in that a common concern with form, and the mode of thinking each form permits, persists between and across them. My first book, Benign Violence, was attempting to push against what I considered at the time to be a certain set of writerly conventions, or expectations, that imposed constraints on thinking. And this first book was also concerned with the function of fictioning in the activity of theorising.

SDS: In our previous correspondence, you mentioned that while you were writing the manuscript for The Faces of Pluto, you were concurrently reading the various texts that appear in the book and that this changed the reading process in interesting ways. In what ways did that practice change your reading, and how did it inform the way the manuscript developed? Does reading normally play a role in your writing practice?

AA: In The Faces of Pluto, I again grappled with a problem I have elsewhere approached, namely, what to do with all the artefactual and intellectual detritus we find ourselves constrained to live inside and pick our way through. This includes all the promises that have been made on behalf of cultural outputs which have clearly failed to elevate or refine, and which may, in the severest analysis, be further engines of coercion or delimitation. I am aware that our respect for this vast and diverse cultural inheritance still conditions outlooks, and so in this book, again, I explored how a less respectful engagement might proceed, in particular, one that refused the demands of diligent and tidy readerly encounters with those cultures of appreciation. Here, as elsewhere, targeted disrespect is a political exigency. This is a question not simply of remaining incredulous before all forms of governmental authority, but ill-mannered before attempts to tidy up and organise one’s thinking and orient how one “reads” both texts and situations.

SDS: In his memoir Gathering Evidence, the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard claims that there is no such thing as truth and that “whatever is communicated can only be falsehood and falsification.” Further, he states, “the aspiration for truth, like every other aspiration, is the quickest way to arrive at falsehoods with regard to any state of affairs.” The Faces of Pluto facilitates an intertextual conversation between the narrator and some of the noted falsifiers among history’s compilers. Bernhard’s notorious hyperbole notwithstanding, do you see any relevance of his statements on truth to what unfolds in The Faces of Pluto?

AA: What I have come to call error writing is absolutely central to The Faces of Pluto (and has a place in other books, like Plague Theatre and Jonathan Martin). This is the activity of falsifying as I write, of introducing untruths and fabrications alongside or imbricated with material I am faithfully reproducing. Sometimes this is deliberate (intentional mischief, embedded criticism), at others it is willfully accidental where I create the conditions that will allow mistakes and fabrications to occur quite naturally (by relying, for instance, on a fickle memory of things read a day, a week before, which I then recount without back-checking). As I write, I keep no notes of my sources, and so there is no easy way of restoring the division between faithful reporting and the stuff I have made up. And I forget, fairly quickly, the less obvious fabrications. Some absurdities remain in plain sight, of course, and most of these are not of my own invention.

I do understand the value of diligent scholarship (and I am a practitioner, at times, of careful citation and reporting myself), but there are other engagements with historical texts and artefacts that the academy (with few exceptions) still seems blind to. And besides, the academy has become more intolerant of entities (people and works) it cannot “read” or decipher with little or no effort applied. Its favoured routes to “truth” have become symptoms of the extraordinary limits it has placed upon what it can see and think. It is not difficult to step outside these limits, and experimental work, it seems to me, needs to concern itself less and less with playing against them.

SDS: A significant share of the criticism in your writing is directed at so-called educated culture and its role in maintaining the status quo (e.g., the self-satisfied academic who has achieved a certain status in work and society and is now only interested in preserving that status, even if from behind a screen of purported dissent). I’m curious if you consider writers of so-called literary fiction to be complicit in this charade, in that many of them are serving up the type of unchallenging, nonthreatening (i.e., middlebrow) literature that fuels a contented apathy amongst its readers, who are themselves the constituents of “highly educated culture.” If so, what do you think the antidote, if any, is to this type of palliative literature that seeks to soothe instead of agitate? Or, as you allude to previously, if the death of the book is inevitable, perhaps an antidote is impossible?

AA: Much can still be done with the book and there are many ways for it to die, including its extension into the palliative literatures you describe. Something can die and yet persist interminably. And nothing is inevitable, I just struggle to imagine a future in which the book, and bookish cultures, are revived, and deliver on the kinds of promises and hopes many still have vested in them. This failure to place much hope in books (and bookish cultures) is nonetheless somewhat liberating (but only in a very minor way), and this is the effect I was attempting to describe. It might be taken as a prompt to make mischief with what remains, and invite consternation too, particularly from the representatives of highly educated culture you have in mind. On the question of antidotes, I am not sure if I am there yet (or would ever be inclined to think in terms of cures or remedies). And when it comes to a critique of educated culture(s), I am just as preoccupied by its impossibility (the impossibility of criticism), insofar as criticism remains a function of what it problematizes.

SDS: Since you brought up “the function of fictioning in the activity of theorising” in your first response, I’d like to dig a little deeper there. In recent years, what some call theory-fiction has become more familiar among general readers, especially of horror and weird fiction, in part due to the publication of some of your own novels as well as those by writers such as Gary J. Shipley, who also operates in this space as a kind of rogue academic. While the practice of melding theory with fiction is not new, the introduction of the term “theory-fiction” is a more recent development. Although disagreement exists over when exactly the term originated and what it encompasses, most agree that Jean Baudrillard’s later work figures prominently, as well as the work of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (also known collectively as Ccru). Researcher Joshua Carswell states in a blog post from November 21, 2018 that there is “a connection in theory-fiction between form and content: form must be contingent with the theoretical task undertaken by its writers, and not chosen purely for aesthetic reasons.” Would you agree that this connection is a defining characteristic of theory-fiction, and what are your thoughts on the intent, value, and possible future of theory-fiction? Should it be considered as a genre unto itself, or is it still more of an approach?

AA: Although these questions interest me, and I would happily listen to someone who wished to tackle them, I have nothing myself to add, or if I did, it would be more of an intervention in the question of theory-fiction than an attempt to account for its prospects. I use terms like theory-fiction (and others like it) as signalling devices as and when I have to, but if I could, I would not use them at all. This perhaps comes from a sensitivity I have acquired from too much time spent in university contexts where some are endlessly territorializing, adopting terms, disputing others, and laying claim to the legacies they would like to align with. In my own work I have tended to adopt a sideways movement to avoid settling anywhere in particular and have strived to maintain the capacity to have nothing much to say about any particular thing.

SDS: I tend to agree with your response, as I also consider these types of terms to be of limited use and often even an impediment, especially if they turn away potential readers. However, I was interested in your take as I’ve not seen the term “theory-fiction” addressed in any interviews with contemporary writers whose work has been characterized as such. Whenever a new term emerges in an attempt to corral the different threads of a perceived similar writing approach, especially within so-called experimental writing, I think it’s important to give representative writers the space to respond to that term. For example, when questioned about it, most of those writers first grouped by critics into the nouveau roman “movement” either soundly rejected the term or were at the very least indifferent to it. Humans do seem to have a nagging propensity to pigeonhole, though, especially things (or other people) they don’t immediately understand.

Moving on, you’ve previously written in a pastiche of Thomas Bernhard’s style. Bernhard was publicly critical of what he perceived as the anti-intellectualism prevalent in his native country, while also repeatedly railing against formal education in his books. At the same time, he makes a mockery of genius in his novels by conflating it with crippling obsessiveness. No one ever succeeds at their endeavors and, in the cases of Konrad’s wife in The Lime Works and both Roithamer and his sister in Correction, those endeavors can even prove fatal. Considering your own thematic concerns, it seems natural that you would be drawn to Bernhard’s writing. What prompted you to use pastiche of his work in the way that you have, and what specifically about his style made it a suitable vehicle to appropriate?

AA: When I wrote The Sick List, which is a Bernhard-influenced monologue, and then returned to monologic writing in books such as The Wake and the Manuscript and The Reading Room, I was aware these might be read as attempts to imitate Bernhard’s style including some of the convolutions you describe. These books of mine are quite different, and diverge from Bernhard in important respects, but the influence is certainly there. Still, this is not so much mimicry, as an attempt to inhabit elements of what I found interesting in Bernhard’s writing. There would be no way of doing that without polluting those elements, or distorting them, by the fact of making a temporary home there.

I had this question of imitation already in view to some extent in The Sick List where I lay into another author for writing in a Bernhardian style and for failing abysmally (so The Sick List claims) to match or even understand the logic of Bernhard’s prose. This embedded accusation and dismissal (of the very fine novella Revulsion: Thomas Bernhard in San Salvador by Horacio Castellanos Moya) was deliberately excessive and was intended as a critique of the widespread practice (among critics) of comparing one author to another who might be writing in a similar vein, and then deciding which author comes out inferior. But I’ll leave that critique in its staged context. I don’t want to explicate it.

I would say that if art and literature are to be doubted within a work of criticism (and these books are as much works of criticism as they are “novels”), such a work of criticism should hesitate, or pause, before considering itself a work of literature, or an art form in its own right. I am, for that reason, fairly comfortable with the accusation that where I have experimented with a Bernhard-influenced style, I have inevitably ended up doing a number on it.

SDS: I like the way you describe your approach to “inhabit elements” of Bernhard’s writing, as well as the idea of “making a temporary home there.” I’m drawn to this idea of an itinerant writer moving around and shapeshifting as needed to fit their own specific purpose(s). And I agree that this is far more than mimicry. It is clear that you are doing something quite different from Bernhard. For the record, too, I find your use of elements of his style to be both spot-on and enjoyable to read, with a little more humor than Bernhard typically allowed into his, which I appreciate, dry and subtle though it may be.

In reading other interviews with you, it struck me that the core writing approach you describe as taking, that of not planning in advance and allowing the initial ideas to “run amok” without allowing them to resolve, is reminiscent of the approach of improvisational music, where a musician or group of musicians begins with a single riff or melody, either planned or spontaneously generated, and expands on it in a freestyle way, until the expansion reaches its natural endpoint. You’ve collaborated with Emile Bojesen, including for The Faces of Pluto, wherein your words and his music enter into conversation. How do you see these collaborations fitting in with your fictive work, and what are your thoughts on the connections between writing and music as very different but compatible means of expression?

AA: On the question of “running amok,” I was more concerned with how ideas might be manifested in writing rather than the frenzy of the amok itself as an improvisational event. This is geared against tendencies to tame, “understand,” domesticate, or explain away difficult ideas, which even the most sympathetic critic may enact as a function of their diligence. And so, for instance, when I write about Nietzschean ideas in Black Vellum, I do so without a second thought for what Nietzschean scholars might consider sanctionable. In this novel, the priest and his automaton of animal flesh are an outgrowth, a textual deviation, where some of Nietzsche’s more disturbing ideas are allowed to persist and interanimate.

My collaborations with Emile Bojesen have tended towards the improvisational, however, and these have taken different forms. So, at times I wrote and Emile responded in sound. His, yet-to-be released album, a response in part to The Faces of Pluto, is an example of this, as is one of our earliest collaborations, Emile’s response to Wretch, titled “The Unknown City” (a phrase from the book). At other times, Emile composed, and I wrote in reply, or we wrote and composed in dialogue, where Emile might produce a fragment in sound, I would reply with text, Emile would elaborate his initial composition, and so on until we were done. In all of these exchanges we are only half responding to each other’s work, and clearly gather influence from elsewhere. Emile is drawing, too, from a broader set of considerations about the relation between sound and experience, which he has written about in some detail.

A couple of things which interest me. Firstly, how Emile intuits into sound the mood of a book or a text and which I find myself recognizing not as the sound that the book demanded, but as a viable and necessary interpretation. Secondly, how writing can be influenced by sound, in a similarly indirect, translational manner. But also, how language displays its limits, its failures, against a soundscape which will always feel much richer, and more open to the realm beyond (our highly limited) intellection.

Even when I am not working with Emile, I think of my writing in terms of sound (the rhythm of the text, for sure, but also what seem to me atonal qualities, and so on). My perception of what I have written/am working on can also adjust quite markedly depending on the sound environment I have just occupied. This extends to imagery too, where, if I have been looking at a certain type of image just before returning to a text that I am working on, I see, or perceive, the contours of that image in the text … or the text at least takes the flavour of the image. These seem to me yet other examples of the diversity of experience that writing can deliver into. They are indicative of the range of different “thinking spaces” one might occupy when working on a text. The specific form of the text (monologic, fragmentary, and so on) is only an element, a dimension in that work.

SDS: It’s stimulating to consider all of the possible sources that can affect the act of writing, beyond the traditional sense of a writer having other writers they consider to be influences (and/or that critics do). I’ve had similar experiences with sound, particularly music, while writing. In one case, I wrote an initial draft of a novel while listening almost exclusively to the music of one particular band. In the end, I realized this music had had a profound effect on the text; yet, it was more of an accident of circumstance than anything intentional. But this idea of consciously viewing thinking spaces while writing as another dimension of a work, equal to an element such as form, is one that I would like to experiment with in my own writing practice.

In closing, you have discussed before the value (and perhaps necessity) of irreverence in literature, particularly in relation to your study of the ancient Cynics. Though the effect(s) of irreverent writing would likely be muted in contrast to the more powerful public acts of the Cynics, what might literature still achieve that it doesn’t now if certain (or all) of its conventions were to be jettisoned in favor of a celebration of irreverence or, as you describe it, a “less respectful engagement” between writers, readers, and previously enshrined “cultural outposts?” Could widespread “error writing” contribute to a major disruption in readerly response to a cultural inheritance? And are there ever times when literature should take itself more seriously?

AA: The situation literature faces, both in terms of its own predicament/future and the wider predicament it may be responding to/staging an intervention in, is eminently serious. Nonetheless, cultures of seriousness (serious study, serious writing, serious thinking) are often associated with set ways of doing things and these might need to be toyed with and disrupted. If playfulness is associated with levity, that is not what I have in mind at all. As for error writing, or any similarly deviant activity, it can only exist in the margins and could not become a model for major disruption without substantial modification. I would be open to that, for sure, but in the knowledge that something I had in mind, and that once felt possible or necessary, has been necessarily lost. Still, I am not sure if I will be using this term much longer (and I have only just begun to), and if it still informs what I do, I may no longer draw attention to it as if it had so much importance.

S. D. Stewart lives in Baltimore, Maryland. He is the author of the novel A Set of Lines and a member of the collaborative publishing project Ghost Paper Archives.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.