Tell me how it tastes

Mia’s dead ex-wife turns up in the middle of the night, dripping. She’s soggy with the smell of the lakebed and gets stinking mud all over the mat. Mia doesn’t know what to do with her, but she runs a bath that’s probably too hot and sits with her back against the bathroom door until she hears it start to drain. Then she pulls the bedsheet up over her shoulders and pretends to be asleep. In the morning they leave for a road trip, Mia and her ex-dead wife.

They don’t have an end point in mind. West, Aliya says, let’s go out west. Wherever we end up. So Mia packs for a week: six shirts four shorts eight pairs underwear two bras should be enough. With everything rolled into bundles by outfit it all fits into her smallest duffel bag. Aliya packs like she always does: armsdeep in the closet, talking the whole time. Mia watches her elbows lock and straighten as she stuffs things into a suitcase. They are the same as they’ve always been—not bloated or gray from a year at the bottom of the lake—and the skin is smooth and whole, not fishbitten. Mia stares and stares and pretends to listen. She’s sitting in the driver’s seat by nine.

First Day

There is a little whistling sound as Mia drives, from a window that doesn’t close all the way. It’s too hot in the beat-up car, but she hates open windows on highways—the way the wind slaps your cheeks and whips your hair into a frenzy. Aliya sleeps with the passenger seat reclined as far back as it goes. She didn’t sleep much the night before. Neither did Mia, listening to things move around in other rooms. Aliya must have picked up every object in the house, opened every drawer and rearranged every cabinet. She even heard the sucking sound of the fridge opening, the thuds and clanks of Aliya moving Tupperware and throwing away milk cartons. When she eventually came back to the bedroom, she sat upright on her side of the bed with her feet on the floor and Mia lay still, imagining the longing warmth of the body beside her.

After the bath Aliya didn’t smell like lake mud anymore, but like something thick and floral. Every year in July all the bushes in front of the neighbor’s house break out in tiny white flowers. At first the sweet smell is nice, but by the fourth day the flowers’ grainy shapes start to swallow up all the leaves, brilliant burning white. You can try to hold your breath when you walk by but eventually you inhale and the air is so thick and stifling that time of year that the smell snakes down your lungs and curls up there, making a home of you.

Mia had woken up just past dawn with that floral smell in her throat. Aliya was sitting with her back against the pillows, reading Mia’s journal.

While Aliya sleeps, Mia drives. She thinks about her manager, who hates last-minute vacation requests, and wonders if she can finally take her bereavement leave a year after the death in question. The vent intermittently belches lukewarm, gasoline-scented air at her, but it’s better than the still stale heat of the car. At one point she tries putting music on, but Aliya shifts in her seat, just awake enough to be irritated, so Mia turns the volume dial all the way down to zero.

The road goes on and on and on. Trees farmland herd of cows change lanes that driver must be high more trees that piece of wood looks about to fall off the truck I wonder how much it costs them to rent these billboards New! Dollar menu special exit 104 Win Big! in Atlantic City After you die you WILL meet God. That one is cut in two by the jagged line of a heart rate monitor flatlining.

Mia stops for gas twice and eats things that come in bags. Aliya sleeps without once waking until the sun has set and they’re crossing into Indiana and Mia’s arms are starting to go numb.

Good morning.

It isn’t meant to sound so sarcastic. Aliya doesn’t seem to notice—once she unsticks herself from the chair she is all energy and excitement and questions: What did you see in Ohio? Have there been horses? Cows? Sheep? Should we play a game to pass the time? Twenty questions or would you rather?

Aliya would rather fight one horse-sized duck. Mia would rather lose all of her toes. Aliya would rather be paralyzed but have telekinesis. Mia would rather have to eat one hundred spiders. Neither of them wants to swim in a pool full of anything but water.

They get off at the next exit and Mia eats something more substantial. Aliya sits in the booth across from her and criticizes strangers’ clothes.

When they’re back in the car, Aliya driving, Mia slides the passenger seat back and stretches her legs out hard until the tendons under her knees start to hurt. She falls into the sticky sleep brought on by motion, feeling the threads of the music on the radio weave into shallow dreams, waking just enough to tun her aching neck from one side to the other.

Mia doesn’t know what time it is when she opens her eyes, but all she sees is darkness and blurry lines of red and white lights. She feels creased and tired. The radio is just playing static, but Aliya doesn’t seem to have noticed. She’s staring forward rigidly, and they’re going so fast, it has to be ninety or more. Maybe Mia is dreaming. There’s something frightening about the look on Aliya’s face—the fixed beauty of it, like an unsmiling doll—so she turns her head back towards the window and follows the lines of light all the way back to sleep.

Second Day

The car is hot, dripping hot, and Mia keeps wiping beads of sweat off her upper lip with a hand that’s nearly as damp. The tiny breeze from the cracked-open window isn’t worth much when the late morning sun is sliding in through the streaky windshield and draping itself heavy all over her chest and shoulders. Aliya looks even worse than Mia feels, her face sweatshiny, the shallow hills of acne across her forehead and jaw bright with it as she slumps in the chair looking listlessly at the window. Is she looking through it to outside, or is she stuck watching the light turn old rain tracks dusty white, suspended somewhere between the car’s inside and out?

Will you turn up the air, Aliya says, again.

It doesn’t work, Mia replies, again.

This car is a disaster. Where did you even get this shitbox?

I needed a new car, after you—Mia cuts a look away from the road, expecting Aliya to look sour, or sheepish, but there is no expression at all on her still face. I didn’t have time to save up.

In a sudden bolt of inspiration, Aliya pushes her hands back across her forehead and into her hair, making a hand headband that pulls her skin tight and her eyebrows up into points.

Get off at the next exit. Right there, look, get off now—she points at the exit sign, her arm a dog fixed on a trembling rabbit. Mia feels the whine of complaint in her throat but she knows she’d give in eventually, she always does, so what’s the point of arguing. She clicks the turn signal on before drifting across three lanes and then stepping down on the brake hard enough that their bodies lurch forward.

Where do you want to go?

Somewhere air conditioned.

There’s a Target in the nearest shopping center, and Mia follows the signs, red concentric circles like the back end of a bullet. They walk through the clean white endless aisles and revel in the tickle of sweat evaporating off their skin. Mia runs her hands over her round forearms just to feel the caterpillar fuzz and make the skin pucker into delicious goosebumps.

Aliya walks ahead, setting the pace. She moves like a dancer—the deliberate sway of hip and shoulder, the cant of her head, chin up always like she’s showing off the curve of her neck. Maybe she is. Maybe somebody told her once that she has a lovely long neck and ever since she’s walked around everywhere like a princess, with her chin tilted up so she has to look at people down the flat line of her nosebridge. Mia follows, leaving a little distance between them, dancing her fingertips across the edge of the shelves. She picks things up and puts them back: sunblock, shampoo, pink glittery children’s toothpaste, as if she were a person here shopping for something.

In the produce aisle they eat berries without paying for them. Mia is full of paranoia and affected nonchalance, and the sweetbright burst of raspberries in her mouth is lost to the taste of her own fear. Aliya laughs her chiming laugh that makes Mia swallow a smile and downs most of the carton. Almost as soon as they’re eaten her face twists up and she runs for the bathroom. Mia wonders about her ex-wife’s dead stomach. After it sat unfed for a year, learning things about rotting, the hungry fish and the curious little crabs and all the hundred thousand different types of bacteria that make it their business to take things apart. No wonder it’s unhappy about the raspberries. Mia knows well the shape of Aliya throwing up into the toilet, the hunched back, the wide open mouth in the blur of her face, the shuddering. Mia’s hands, of course, on the sticky skin of her wife’s arm, pushed into the curls at the back of her neck, her own drunken discomfort compressed into the shape of a pill and swallowed.

In the aisle where Mia waits for the bathroom door to swing open again, the summer wreaths are stacked deep, the holes in the middle of each one merging into a single deep empty space that she can reach her arm into up to the elbow to press the cold perforated metal behind them against her palm. The sunflower wreaths are made from perfect plastic leaves and perfect plastic petals and perfect plastic brushes bristling with gummy yellow tips in the center.

Sunflowers were Aliya’s favorites. She liked to bring them home and stick them in anything that could hold water—jars, cups, plastic takeout containers—and Mia would clean up the petals they dropped and replace their foggy water. Two summers ago, when they were driving back from visiting Aliya’s family, they passed a field of sunflowers which all stood to attention with their faces lifted to the sky. Mia gazed down the lines of them, the spaces between the diagonal rows that shifted and opened as she walked past, just big enough for a body to slip into. Aliya took photos, and in them the field looked endless and gorgeous. But it was only near the road that the flowers saw enough sun to be so showy yellowbright. Farther back, she could spot some of the petals drooping soft brown wrinkles and heads hanging lifeless from their twiggy necks. Big dark purplish heads, furred with seeds, looking at the ground.

This is how Mia remembers it, comforted by their remembered imperfection. But in the photos Aliya took, you can see the head of every flower for a mile, and they are each sunny and smiling, ever petal plastic perfect.

They find a hotel near the Target. It’s expensive, but Aliya is so excited about falling into a big white bed with crisp sheets neatly folded. Nothing around her has been crisp or neat or white for a year, and Mia thinks about sludge and creeping shrimp as she hands the bored clerk her credit card.

Everything in the hotel is white, except for the things that are an indeterminate shade of beige, and Mia gets lost in it. The weight of all that brightness presses her chest down into the too-soft bed. She searches for breaks in the light, for shadows or holes, but the only thing that moves in the room is Aliya, as she throws herself onto the hungry duvet. She’s hard not to look at, magnetic, sinuous even as she wiggles under the blanket to relish its comfort.

Third Day

They leave late. It’s hard to give up the cold comfort of the hotel and get back into the car, where the miasmatic air is hot and stale and the peeling black leather on the seats burns Mia’s thighs through her shorts. The road out of Nebraska has been recently paved so it’s a smooth black that eats light from every direction. A billboard tells her Jesus is alive and the next advertises an adult superstore.

Mia watches the road and traces the shapes of bug bodies splattered on the windshield, all the little cavities inside their complicated bodies emptied into a greenwhite explosion on the glass. There are fewer bugs now than there used to be, everybody says it.

Aliya talks. Do you remember in college when we climbed up onto the roof of the chem wing just so we could have a quiet place to ourselves?

Mia smiles, a soft involuntary smile. It was so cold, she says, it was almost three in the morning, I still can’t believe you talked me into that.

She remembers mostly the fear, first of the height and then once they were up there, that someone would spot them and they’d get in trouble, and she remembers the way she shivered a little performatively, because she knew it would make Aliya, who never got cold, take off her jacket and put it around Mia and pull her close.

Well your roommate was impossible. And my quad was out of the question.

Another bug finds the end of its life on the windshield. It has a lot of insides, for something so tiny. Mia thinks about the moment of impact, hard exoskeleton telescoping into itself and all that soft stuff with nowhere to go. Does it feel the body giving way, or is it already insensate, its mind, such as it is, giving it the small mercy of ending things before that end becomes tangible? It was true that Mia’s college roommate had been impossible, had banned all visitors even during the day, and at the worst of it had kept tabs on Mia’s comings and goings in a chart taped to the wall. Shivering on the fire escape she had turned her head into the warmth of Aliya’s body and felt grateful and frightened and alight. Now, squinting into the sun, she wonders whether Aliya had liked the threat of getting caught, if she would have loved to be known for getting into trouble for fucking on the fire escape. And of course Mia would have been a part of it too, stuck onto the end of the story. Of course that would happen to Aliya and Mia.

That’s how people talked about them in college. Aliyanmia, all one word, her own name suffixed on. And all the people she knew watched them with wide eyes and mouths open already to tell the story to somebody else. You’ll never guess where Aliyanmia were last weekend. Did you hear what Aliyanmia saw yesterday. That’s how people knew her.

The glare of the light on the windshield turns each of the bugstains bright white, filling up the space between them with dust so that Mia can barely make out the cars on the road. She flips on the wipers and they smear the mess all around the windshield until it’s spread thin enough to see through. She drives and drives.

Aliya is making big sad eyes and asking can’t they please stop somewhere. It’s not fair how Mia’s gaze catches on that face, one she hasn’t seen since their early years.

If we keep stopping we’ll never get anywhere. And all these hotels are expensive. Where are we really going? Are we actually trying to get to the west coast, Lee? The nickname is reflexive, carried on the surface of her question like a tick.

I’m tired, Aliya replies. I want to lie down. And it’s so hot. We can both have a rest. Don’t you want to rest?

This shouldn’t make Mia’s heart ache and her fingers tense closed and open on the wheel, but it does.

You could try driving for a while, if you want me to rest.

But Mia is already looking for exits, and Aliya must see the concession in her expression, because she just sits back and tilts her head up and towards the window, so that the glare of the sun obscures her face and all Mia can see is the line of her throat chasing the side of her chin.

In the Burger King, Aliya revives. She doesn’t order anything, but watches Mia eat with unexpected ferocity.

Tell me about how that tastes.

Mia sucks another blob of milkshake through her straw. It’s sweet.

Cold?

Yeah, cold and sweet. Do you want some?

No. Aliya pushes herself up from the table, both hands flat with her fingers spread out wide, and paces around the restaurant, eyeing the other customers. She fixes on their mouths, the ceaseless up and down of jaws, the stretching of lips away from the face as people take bites of their foot. None of them take much notice of her, but Mia watches Aliya’s deliberate steps, her figure a knife slicing between the plastic wood tables, sharp against the thin veneer of brick on the walls. And there it is again at last, the old thrill that seeps through Mia’s nervous system when she’s near Aliya. The excitement of her—the knowledge that anything could happen next, that it’s all finally out of Mia’s hands, that she can sit back and let Aliya happen. She has to bite the inside of her cheek, hard, to stop the smile that she doesn’t want to overtake her.

Mia finishes her milkshake fast. It’s that artificial strawberry flavor that’s too sweet, and it makes her nauseous, but she doesn’t like to leave things unfinished.

They end up in a motel, in the only room left, and the air conditioning is broken. It’s still midafternoon and the filmy white curtains aren’t doing much to keep the sun out. Aliya takes her pants off and falls asleep on top of the sheets, her legs long and loose on the bed. Mia turns on the TV and clicks through channels, slipping into the torpor of underwater thinking. She watches people demolishing houses, pulling down chunks of drywall and crashing sledgehammers into tile, talking about how much better it will all be when they’re done.

When Aliya wakes up it’s dark and Mia’s eyes are sore. The thousand colors of light coming from the screen are pale on her face, the corners of the room thick with shadows.

Aliya rolls and stretches and hums loudly, and when Mia doesn’t say anything she arches and presses up against Mia’s side like a cat.

Morning.

It’s night. Mia presses the mute button and puts the remote carefully on the corner of the nightstand. The tiny people dance through their houses in silence.

Well, I just woke up. So that makes it morning.

Aliya pushes herself up on her elbows and pulls Mia’s head down to hers and kisses her. She’s sleep sticky but her mouth is strawberry-sweet. Mia can taste her breath and it’s a snake in her throat, filling her lungs and stifling her. She turns her head to the side, gasping for air, and Aliya’s mouth is on her neck, sending sparks down her body. She’s tired and her eyes hurt and it’s too hot for this, but Aliya’s kisses are insistent enough to press the back of her skull hard against the headboard and it seems like more work anyway to push her off, and it’s too hot to do anything else either, so Mia slides down the bed until she’s on her back and lets her hands crawl up her dead wife’s sides.

Aliya’s body is almost violent in its desires. The slamming of her hips, the slick pressure around Mia’s fingers, the hand she has placed on Mia’s chest for balance, twisting her t-shirt tight enough that the seams pull tight into the back of her neck and her armpits. But Mia doesn’t notice these things. Her wife’s body move over hers and she stares at the sweat that makes her collarbones gleam from a million miles away. There is a dullness settling its weight back over her body, and she wants it to scare her but all she feels is dull and still and solid. And as Aliya shudders on top of her, dripping sweat onto her shorts, everything that throbs and beats inside of Mia, her heart and her stomach and her lungs, all melt like candy in the sun and leave her hollow and sticky inside.

After Aliya rolls off her, breathing heavily, Mia washes her hands in the bathroom. She retches over the sink, but all that comes out is a dribble of pink milkshake.

She lies naked on the dirty tile floor and tries to figure out what to do, but all she can see is the hollow afterimage of Aliya burned into her retinas.

Fourth Day

Mia wakes up groggy, sleep trying to lift her back up into its embrace. Aliya is a still weight in the bed, stretched out naked with the covers scrunched near her feet. Quiet as a spider, Mia tiptoes to the bathroom to wash her face. She stares at her eyes in the mirror until they start to look like someone else’s, and they frighten her, the intensity of the gaze, the deep shadows underneath them.

On the bed Aliya looks so much like she has a thousand mornings before that Mia almost crawls back in next to her. How many times has that soft face made her smile, eased her back to sleep in the late hours, kissed her awake? She puts one hand into her mouth and bites, hard, and it makes her feel stupid, but the sharpness is good.

She hasn’t packed properly, but she grabs what she can—half-filled duffel bag, keys, wallet, phone.

The last time she ended things, Aliya had blown up her phone for weeks, an endless stream of calls even after Mia had blocked her number. It hadn’t let up until—well.

The tiny wheels of the duffel bag drag across the parking lot instead of rolling, building up mountains of gravel in front of them. Mia’s heart is beating fast, despite the heat; she’s feeling keyed-up and sweaty, her shoulder blades tight, her hands twisting the keys back and forth from one grip to the next. Nobody is looking at her. She almost runs to the car, shoves the bag into the passenger seat where it slumps like a corpse. Tearing out of the parking lot and onto the other side of the highway, she heads east, toward the thin morning sun, toward home.

She realizes how badly she’s speeding when she keeps passing cars on her left. Deep breaths to force the heart to slow, to loosen her grip on the steering wheel, to ease up on the gas. It’s hotter still than yesterday and her fingers are sweaty, her thighs fusing with the seat underneath her.

Every time she blinks, she expects darkness, but instead she sees orange, like staring into a light.

The phone starts buzzing in her pocket and it spikes her back into panic. It could be anyone calling, but she knows it isn’t, and she’s suddenly so aware that her skin is prickling all over.

Mia slams her hand into the hazard light button and pulls over on the shoulder of the highway. She picks up the phone with her eyes carefully closed. Outside the car the air is somehow more oppressive, heavy with humidity. The gravel under her feet gives way to a steep hill just past the guardrail, with gray stagnant water pooled at the bottom of it. She leans back from the rail, listening to the roar of cars blazing past her. She is surprised to find that she likes how the endless sound of them fills up her head.

Carefully she peels the phone out of its gummy plastic case and drops it into the ground. The screen shatters, but it still lights up to show three calls from an unknown number. She picks it up again and throws it as hard as she can, straight down, too short a distance. There’s some kind of sound welling up in her, and she lets it crescendo while the cars scream past her until she is screaming too, wordless and hoarse, while she grinds little bits of glass under her feet and stomps on them like a child.

Even with chunks of screen gaping like missing teeth, Mia can hear her phone start to vibrate. She draws her arm back and hurls it into the water, and she can’t hear the splash but she can see it, the water dancing up and away from the intrusion before accepting it.

Mia is light as she steps back into the car, floaty like she’s walking on the moon. In the car she turns on the radio and the air, even though it’s hot air, and she drives without thinking about it because it’s easy, it’s all part of her, the car and the road and the hundred other cars on the road, and she slides through them all with the ease of breathing.

When she ended things with Aliya for the last time, she couldn’t bring herself to turn off call notifications and so instead she just got used to the sound of buzzing, and it followed her around like a persistent bee for a week. She never picked up, though, so it was a surprise when she came home from an evening shift to find Aliya, drunk and angry and soaked in the summer storm, trying to open the front door with the wrong key.

It was just instinct, Mia told herself, to put the palms of her hands on either of Aliya’s arms and hold her still until she calmed.

They fought about everything all over again, the quickening rain drowning their words, Mia’s umbrella forgotten, the drops streaming down her forehead and into her eyes. But she didn’t cry from the sting of it and she didn’t cry from the way it hurt to see Aliya like this, her clothes and hair clinging in a way that made her look small, her makeup washed half away. She didn’t let her in, either, and get her dry clothes and make her a mug of hot water and say it would all be okay. When they had exhausted themselves with shouting all that was left was Mia saying the same words again and again: I don’t want I don’t want I don’t want

The water running down Mia’s forehead now is salt sweat and she pushes it around her face with the back of a hand. The traffic has cleared up and the trees outside the window are unchanging and the lane lines ahead are unchanging and the air is unchanging and everything in the world is still except for her, a slingshot down the black line of road, gathering speed.

Big green signs tell her where she is—stay on I-80 and she’ll be home in a few days. And once she’s off the highway she’ll turn left at the gas station and pass the shopping center and then she’ll drive over the bridge where—

The road ahead of her is splitting off into a dozen directions, sprouting exits like branches, but what frightens her is that in the heat and the stillness of the air, there’s a slick layer of light hovering just above the road ahead that looks like water pooling in her path. And she sees Aliya, driving away tht night drunk and blurry with tears, and the storm getting louder and wilder, and the crumple of the car’s body against the barrier on the side of the bridge and then its fall, which would have seemed slow, for such a huge thing, into the lake, and the black water closing like a camera shutter over the last spot of silver. Mia swerves out of her lane with a speed that makes her body jerk towards the wheel and takes any exit that promises the safety of black solid asphalt and by the time she has calmed enough to read road signs she’s already miles away from 80, driving with the sun slicing obliquely into her passenger window, nose pointed north.

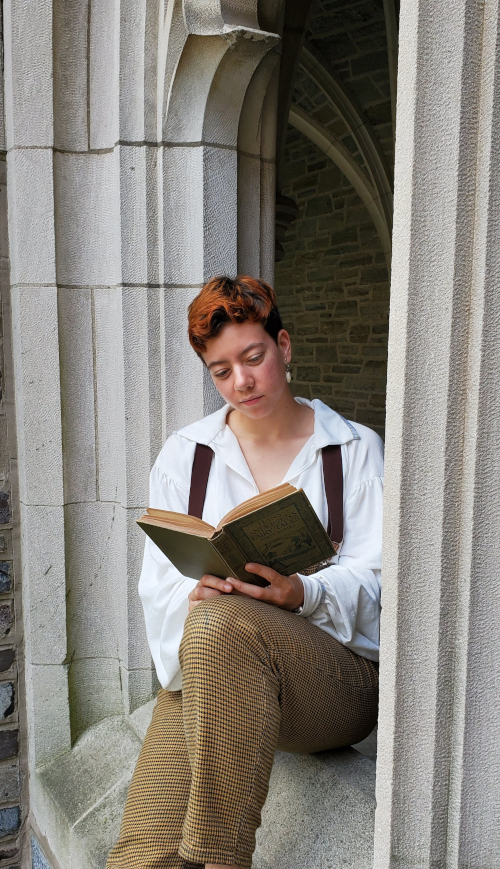

Mini-interview with Arielle M. DeVito

HFR: Can you share a moment that has shaped you as a writer (or continues to)?

AMD: I don’t have any flashes of insight or touching childhood memories to share here—writing isn’t something that’s formed in moments, for me, but rather is a thing that stalks after me, with its paw pads silent on the ground, and always has since I first held a pen, and always will until I lose words forever. It’s the cloth that folds up around everything else in my life and gives me a place to put all the moments. This morning, sitting on a rock in the woods at 6:56 a.m. looking for squirrels while my hands froze and my butt got sore, I saw a fat American robin land on a branch near me and watched the frost melt away from the suggestion of warmth from its talons. I think that moment shaped the writer that I was today, at least.

HFR: What are you reading?

AMD: Right now I’m reading Lauren Groff savoringly and Sylvia Townsend Warner voraciously; and as much nonfiction about ecosystems and rewilding as I can find in the library.

HFR: Can you tell us what prompted “Tell me how it tastes”?

AMD: This is one of the stories I’ve actually held onto the longest, with its first iteration from a class assignment in 2019. It wasn’t about a road trip at the time—it was about a woman escaping from her (un)dead wife by moving into the flower aisle at a Michaels, because I was always enchanted by all those crisp fabric petals as a child, and I loved the image of holding them up against the silky frailness of real flowers. That image barely made it to this version, but the car running into the river remained exactly the same, as did the scent of the little white flowers (a feature of my college campus). The road trip element clicked when my wife and I drove all the way from California to Ohio in five days in 2020, outrunning COVID closures, and I spent more time noticing billboards that week than I ever had before. After that the story hibernated for a long time, and resurfaced this March for my writing critique group in much better shape.

HFR: What’s next? What are you working on?

AMD: I always introduce it as “a book about trees,” because it’s a complicated beast of a novel with a lot of different themes and covers so much time that it’s hard to describe the plot. My elevator pitch is “Lauren Groff’s Matrix meets The Overstory,” because it’s set in two different time periods—a few years in the late 1100s and a long stretch from the 1700s-present—in a forest in Sweden, and explores the changing relationships of humans to their environment through the great ideological upheavals of Christianization and the industrial revolution. And it’s all told from the perspective of a tree. It makes sense when you read it, I promise.

HFR: Take the floor. Be political. Be fanatical. Be anything. What do you want to share?

AMD: It’s not going to change. Whatever you’re waiting on—be it politics, or a person you love, or human nature, or your life to just turn itself around into something romantic and enchanting—it won’t change on its own. You have to force yourself to believe this, because there’s something about the cycle of days/weeks/years that makes it easier to wait for something to happen. But it won’t. You have to make the difference yourself.

Arielle M. DeVito is an agency assistant at Jabberwocky Literary Agency, and a recent graduate of Stanford University, where she studied English and Creative Writing. Her work has previously been published in Broken Antler Magazine, Gramarye, and the Columbia Review. She’s hoping someday to put her juggling, unicycling, and aerial skills to work by running away to join the circus, but until then she keeps herself entertained sewing historical clothing and playing the accordion with her wife and cat, Peppercorn, in Philadelphia. You can also find her at ariellemdevito.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.