In Pineville Trace, Wes Blake tells the story of Frank Russet, a former revival preacher who has escaped from a minimum-security prison in Kentucky, where he was being held as a con artist. As Frank and his feline companion named Buffalo journey west to freedom, Blake paints a triptych of the escapist—his newly forged existence on the road, his previous dishonest days spent preaching, and at the centerfold, the internal life of a man understanding his own desires.

The novella opens with Frank’s journey to Bell County Forestry Camp in eastern Kentucky, but very little is ever said about the prison, except that Frank’s escape from it becomes the deciding parameter of the rest of his days. By Frank’s own admission, the prison was “after all, not so bad,” and he would have been released from it quickly for his non-violent crime. But his escape grants Frank the liberation of the materialization of the entrapment that he had felt long before his arrest. In condemning himself to a life on the run, “he was free from himself. He never had to be himself again.” The prison is only a means by which he is able to escape from his old life. In not serving his short sentence, Frank believes that he will now be forever spared from the confinement of social relationships and the choices of his past.

Time and again, Frank’s luck seems improbable—he escapes seamlessly from prison, finds a house that aligns perfectly with the one of his dreams, and acquaints himself with well-intentioned people on his route who help him from a distance that prevents suspicion or intimacy. Yet, as soon as a new setting seems to promise safety and comfort, Frank’s restlessness brings him back to the road. Early in the text, and only once, Blake provides a chapter written in the first person that reads as a journal entry depicting the conception of this story. It is here that he best summarizes Frank’s central struggle, calling it “the story about getting what you want. And the story about not getting what you want.”

Frank’s encounters with other humans are intentionally fleeting and perfunctory. For Frank, one of the primary appeals of his escaped life is that he no longer has to “feel so bad about the distances that he couldn’t close … The distances that had stretched out between himself and the world. Between himself and other people.” In his new, solitary life, Frank believes himself to be free because he is no longer aware of others’ expectations of him. As a result, much of the book is spent inside Frank’s head, including the primary relationship of the novel between Frank and Buffalo. It is in the depictions of the profound tenderness of Frank’s love for his cat that Blake’s writing shines brightest. The weather, seasons, and trees fill the pages as the other main characters and serve as vessels of Blake’s precise, visionary prose. In one of the most quietly impressive passages of the text, Blake writes:

The winter tried to change into spring. The change came in fits and starts. Rushing into warmth. And then, reconsidering, the world rushed back into cold.

Blake’s writing provides a contemporary case-study on artful, effective minimalism. The book is small, but it is not a quick read—the intentional, deceptively simple words prevent us from flying through the pages, as each line carries enough weight to demand real consideration. The effect is an introspective, haunting tale that remains with us.

A novella-in-flash, each chapter of Blake’s book is intended to have the ability to stand on its own. Such a form poses a risk—when done poorly, the work has the potential to appear either as a gimmick, with half-baked, underdeveloped stories comprising each chapter or disjointed as a larger text that fails to convey a unified message. Blake’s attempt, however, is a definitive success and a gift to us, who are left with both morsels of beautiful flash fiction to return to, as well as a novella that prompts self-examination on the issues of one’s honest desires and how to live with one’s past.

Frank’s movement between lives imprints on his audience the sense of the internal inquisition that arises during periods of transition. Frank’s circumstances appear extreme, given that he is brought to determine who he is outside of all his past relationships and his previous roles as preacher, con man and prisoner. His is the same reckoning, however, that accompanies all human metamorphoses from one stage of life to another, asking whether we get to choose the pieces of identity that withstand all changes to our environments, or if there are predetermined elements of the self that endure forever.

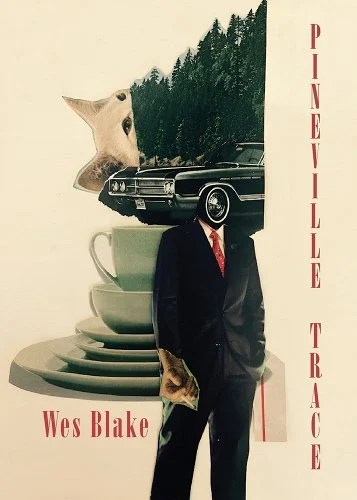

Pineville Trace, by Wes Blake. Etchings Press, September 2024. 140 pages. $12.00, paper.

Mia Carroll is an engineer and writer based in Manhattan, where she lives with her husband. She writes essays, short stories, and book reviews.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.