How many Sundays did it take me to finally write about the new graphic novel from Olivier Schrauwen, Sunday? Get up ah. According to the calendar, this is my 21st Sunday with the book, and I think that in itself deserves some kind of award: like Olivier’s cousin Thibault I have not traveled very far to begin writing this review, the book staying within the borders of my apartment. Get on it. This was not initially the intention, and this is not to criticize any of the fundamentals of story, but over time I came to embrace the conditions of my internment. There are great imaginative dividends from page one and I recommend that you pick up this Schrauwen novel today, as quick as you can. Like a sex machine. No, it is something more ecstatic, spirited, and deliberate that kept me from finishing until now, and perhaps you suffer this uncomfortable tendency too: the fantastic smells captured between these pages are peak, deserving acclaim, bar none. Let me explain.

Olivier Schrauwen is perhaps not a known commodity in graphic novels, offering stories of fantastic proportions about family members (Arsène Schrauwen is back in print this year from Fantagraphics), science fiction futures starring himself, out to sea drunkards, and now, a day in the life of his cousin Thibault. I think he remains a hidden talent of the alternative comics landscape, standing shoulder to shoulder with titanic contemporaries Dash Shaw, Chris Ware, Eleanor Davis, Lynda Barry, Daniel Clowes, and Charles Burns in terms of advancement of the medium. In regard to content, I associate him, fairly or unfairly, with the novels of Alejandro Jodorowsky, whose Where the Bird Sings Best enters into speculative biography as he recasts the surrealistic feats of his Jewish Chilean ancestors in an effort to transcend the trivialities of family ancestry and life stories to catapult these characters into the status of myth. Get up ah. We know this to be unenviable task, as writing about anyone from family tends to bottle expectations, let alone to recast them within melted landscapes similar to that of a B-movie porn-obsessed Salvador Dali. If you have watched any Jodorowsky movie in your time, however, I don’t need to tell you how oddly felt and strangely compelling his narratives are. So Schrauwen is playing with similarly unmoored techniques, where story can take off from anywhere and go across any set piece or genre without so much as a second glance. Get on it.

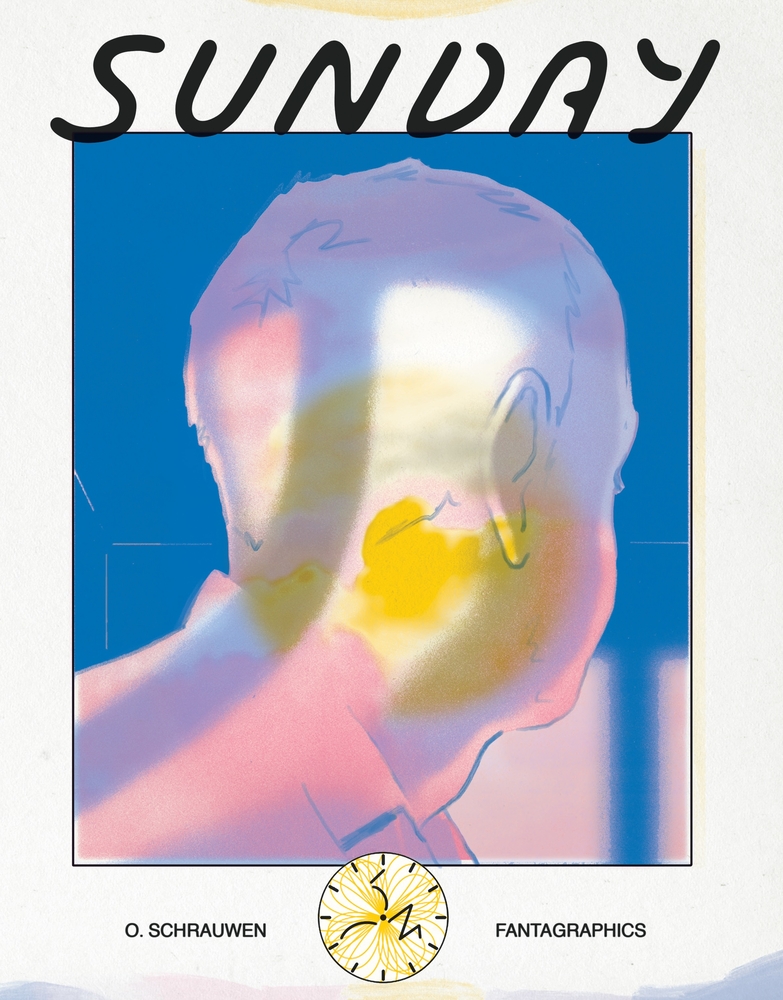

This strategy for storytelling plays out marvelously in the dynamics of the written word, but even more so with Schrauwen’s expertly crafted books. Like a sex machine. You begin to feel a lift in yourself, simultaneously in the pit of your stomach and in your spirit, as if the text is possessing you and making you commit your own hand to sketch out the unfolding events. There is an immersive quality unlike any other when it comes to Schraweun’s eclectic style. In the same way, I do not have the faculties to describe this art except that there is an almost industrial catalogue, experimental pop art sensibility to every page Schrauwen inks, where characters are rendered plainly and within common proportions, yet thrust across so many different layouts and color schemes to enliven any first time pass and keep us coming back for more. This type of art is as close to drugs as you can get. Get up ah. That is, if you do not already find yourself stopping to take another deep sniff of the page, the rich memory of the last whiff compelling you to indulge such animal behavior behind closed doors. (Don’t tell my mom.)

Further, as a book object, the heft of this book demands sedentary nature, as it does not lend itself to easy transport to and fro. Like a sex machine. It is approximately the size of a coffee table book and really owns its presence at 474 pages. Another debacle of the extreme enjoyment of this book: that of watching the slacker Thibault and his Sunday get whiled away. Get on it. This narrative does not sound like much on its head, but once you collect yourself after the book is closed, finding your shirt, socks, and other personal effects, you have trouble distinguishing your Sunday(s) from that of Thibault. Is James Brown also stuck in your head? Get on it. Are you avoiding a looming deadline too because it is your weekend? When you send that text, will the other person respond with similar enthusiasm or did you just ruin any grace you previously carried? What ugly, personal thoughts can leak out of your head when given to the banal existence of living aimlessly indoors with a phone with a broken screen? It is these questions and more that Thibault’s ineffable example uproariously and provokingly lays out for us, and while mileage from living so closely inside one narrator’s stream of consciousness may vary, no one can deny that the artful milieu of this book leaves a smile that is hard to erase on close. Get on it. Still, the question remains: what will I do with my Sunday tomorrow? Get up ah.

Sunday, by Olivier Schrauwen. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics, October 2024. 474 pages. $39.99, paper.

Jason Teal is the author of We Were Called Specimens (KERNPUNKT Press, 2020), which was a finalist for Big Other’s Reader’s Choice and Best Fiction Book Awards. Writing appears in 3:AM Magazine, Quarterly West, SmokeLong Quarterly, and Vol. 1 Brooklyn, among other publications.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.