I Tell You This Now by Daniel Lawless invites us into an intimate viewing of family albums and photography from the Polio Ward in Louisville, Kentucky, 1943-47. As a lookback at when the dead were still living and the hurt that remains in the aftermath of domestic violence and sexual abuse, this viewing is necessary because the mentally ill are akin to “lightning bugs,” as Southerners call “fireflies,” the “lonely gods / Of the backyard.” Through the poem “Fireflies” and elsewhere, Lawless examines the potentialities of the lightning bug, whether it is “Trapped in a juice glass … Or, tapped with a stick, Set free with a magician’s flourish, / According to your cold your wondrous heart.” Lawless defies overwrought cliches (“you dears / Carrying your little lanterns behind you”) and presents an imperfect speaker with his own comfortable entitlements and set of inheritances that stick with the speaker even as he physically moved from Kentucky to Florida.

Structurally, I Tell You This Now is broken into three sections, with the middle section consisting of ekphrastic poems written with the cinematographic lyricism of Charles Reznikoff.

The collection begins with “Family Photographs: My Brother, Solar Eclipse, 1965.” We are introduced to the speaker and his family members before and after their diagnoses with mental disorders and departure in the sanitariums. Grief flows throughout the first section, along with childhood trauma, viscerally described. We face eye to eye with pedophilic pastors who “moan[ed] as he caressed [the speaker’s] nape,” for instance. This grief feels attuned to the speaker’s own relationship with others and with death, as he obsesses over memento mori like the Dying Pit Bull at the End Days Christian Church on 22nd Street, and imagined conversations with the dead sister, lover, and friends. The “[g]reat rumbling Red Square tanks of” grief appear too as “[t]he black fluster of wings / Before the hard crack before getting at the soft meat beneath.”

Stylistically, these poems in the first section are conversational, as Lawless directly addresses the “you,” who is at times the reader and at others the ghost of the dead. The diction belies the speaker’s habitual evasion of the issues at hand: as he retraces the caress on his nape and memories of his brother before he has lost his sense of self. This evasion, in addressing objects as friends and in the deep etymological dives, is utilitarian in getting the poet across the gulf of what he means to say.

To illustrate, in “Rose,” an elegy for his sister, M.L., Lawless writes, “The rose which only words far from the rose can describe / wrote the great French poet Aragon. / And how else should I speak of you, dearest sister, / on this your death day?” The incredible lyricism in comparing his sister and the rose, and elegant things are striking in its specificity (“marble bust of child’s head hovering in the velvet curtains of Ingres’ ‘Portrait of Jaques Marquet De Montbreton De Norvins’”) and function as the “scraps of memories” that the “dead live on.” The dead in Lawless’ poetry are listless, “[a]lways hungry, come-calling us by their name.”

The second section turns away from Lawless’ familial and personal relations in brushes with mental illness, illness, and aging towards ekphrastic poems written after the photographs and captions from the polio ward. Set in the decade right before the polio vaccine was invented, Lawless hones in on the “implacable, un-scratchable itch” of these young patients, who are rendered immobile by the virus. If the first section is conversational in tone, the second section is stately and dry, reminding me of the cinematographic unfolding of Charles Reznikoff’s poems. Lawless’ peering into and use of persona poems are poems of witness that speak to the propulsion and agony that is bookended by a recast Florence Nightingale. Much as Lawless often describes the awry saint, it is telling that here, the saintly figure is more a caricature, an “aging monster … Roald Dahl’s Headmistress Trunchball.” Yet, it is also she who “draws this cozy pink coverlet / over his iron lung, a simulacrum of devotion.”

What should we make of the rose of the speaker’s sister and the pink coverlet of the monster of a Florence Nightingale? Lawless addresses this in his third and final section, which with the why of poetry writing. If poetry allows Lawless to reach towards the beyond, and create the pretension of communion, “as if [he] could touch it, the fine film of sepia dust left by my fingertip / on the cold windowpane between us,” then even if poetry is painful, it is as necessary as daily living. We see the realities of mental disorders unfold: the speaker’s brother after the onset of the symptoms, as the speaker overhears the mother say to her friend “in a voice alchemically compounded of pride and shame.”

Poetry is also a kind of blessing for Lawless. In the eponymous title poem, Lawless wishes that after the terrible whirlwind “[b]lew through it was as if on a train the conductor / Had poked you and you arrived out of the darkness / Suddenly awake to a strange new city, utterly happy.” There is this excitement of youth, of travel to a foreign place, of a promised second coming that is not possible in the real world.

“[H]ow is it even etched on this familiar park bench / On 77th Street set among overturned pink children’s bikes / And wildflowers you somehow frighten me?”: This power in the evocation of a name, as the evocation of the speaker that is not the speaker frightens because it suggests that the speaker is not the only one but may be replaceable or interchangeable. This is a far-stretched worry in the context of the collection, however. That is because Lawless emerges from the domestic abuse and sexual violence that was alluded to and as a survivor chiseled out of “the smell” that “wouldn’t wash off,” sings and in his singing, lays to feeds the ghost of the dead and himself.

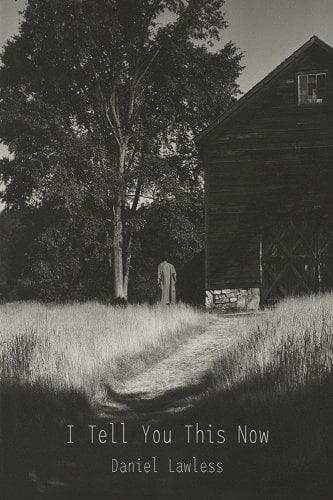

I Tell You This Now, by Daniel Lawless. Červená Barva Press, February 2024. 72 pages. $18.00, paper.

Tiffany Troy is the author of Dominus (BlazeVOX [books]. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, Associate Editor of Tupelo Press, Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review, Assistant Poetry Editor at Asymptote, and Co-Editor of Matter.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.