“Graphic novel” or “graphic narrative” have become the terms used to describe comic books with a literary bent. I’ve always insisted on calling them comics, but Optometry really is a graphic novel, narrative, because it is a story of images and visuals. This book is not so much light on words as it largely functions without them: words stop appearing after the first few pages, only returning at the very end. Arguably, the book could exist without any at all.

The premise here is simple—a young girl visits an optometry office. When she goes into the back to stare into the machine that flicks images past her eyes, we become sucked into those images, the machine even, and from there, are transported through myriad worlds, each ruled by a different artistic style or medium. The pages are unnumbered, and so the only way to track that you are progressing forward is to feel the heft of the book move from your right hand to your left as you flip through.

I don’t want to try to provide much more in terms of a synopsis, because the book seems most of all about experiencing something. We are largely trained to look to captions to explain images to us, words speaking for pictures, but for most of this story, we can only make meaning by juxtaposing what we are seeing on one page against another. Much of the book lacks a real narrative arc, in the best way. Some pages are gridded, with panels and gutters (gutters are the traditionally white space between the squares of a comic), but the form is not rigid: for example, the girl we follow can step out of a panel into the gutter. Early, we get so close to an image (or maybe far?) that the entire page is speckles of color, like getting too close to the printing on an old comic book. The speckles are jagged, irregular, kaleidoscopic, though, lacking machine precision, and as they grow smaller, more tightly bunched, they become harder to pick out, the pages seeming to turn white, every color collapsing into each other.

Time then seems to collapse, as the girl spots herself in a maze and chases round and round, even as we are moving forward (page by page). We can’t tell which self is chasing, which chased, or if it ever switches. This switching possibility makes it seem less an original/clone relationship than a prism splintering light, a funhouse mirror replicating, that each part (each person) would seamlessly collapse back into the whole. Reading, I feel as if I am trying to move in two dimensions. There is depth, but also, all particles are only light. Occasionally the jumps from panel to panel make it seem like you aren’t moving or are moving backward.

At some point, light and color are lost, pages are black, the faint lines of the girl, of panel edges, are now white. It’s unclear if, as my eye moves from panel to panel, I am witnessing a change in time, or if I am examining many iterations of the girl at once. Without gutters, the lines collapse the form of the comic, collapse what boxes mean. The grid becomes tighter, until the form of the girl’s body overlaps, contains, many boxes. Time and space collapse: we lose the panel and gutter relationship that represents moving through time and space in a comic.

Dissolution and reassembly, images reminiscent of space invaders, of cross-stitch and needle point patterns, soft lines of life rendered as 8-bit, as pixels; once more light arranged and rearranged. 3D glasses, the introduction of photographed hands, a face, a jarring reality, then three dimensions of a sort of claymation effect. After a barrage of styles, we return to line drawing, depth is flattened—the many media feel like flicking through timelines, a multiverse.

Text is reintroduced to this narrative just a few pages from the end, and part of me wishes that it didn’t—that rather than using words to impose meaning on what has been an almost entirely visual story, we were left to make sense of the world of Optometry in more or less the immersive sense we had been for countless pages (as in, I can’t easily count, there is no numbering). Of course, I understand the desire to provide meaning, context, to shape what the images and experience has been for us, and comics are very much a form dependent on this interplay. Reviews aren’t meant to “spoil the ending,” so I won’t say what these last words are, but the idea of “spoiling the ending” means that there’s a clear beginning and end here, and one of the delights of this book is its circularity, its winding nature, its fracturing fractals.

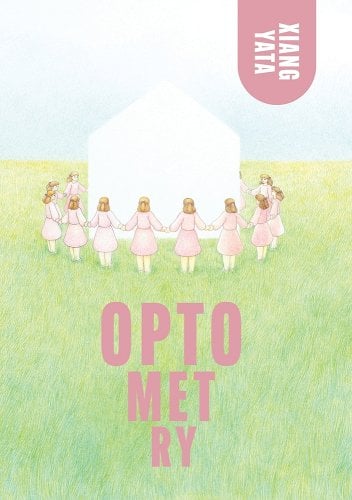

Optometry, by Xiang Yata. Tampa, Florida: Driftwood Press, November 2023. 260 pages. $34.49, paper.

Sarah Shermyen is an acquisitions editor at UGA Press and holds a PhD in English from the University of Georgia. Her own writing—scholarship, prose, and reviews—has appeared in Studies in American Humor, Image Journal, The Georgia Review, and Southern Review of Books.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.