You should read Aditi Machado. You should read everything she writes—I am on that path myself, but I’m only two books in, so we can race each other if you start now.

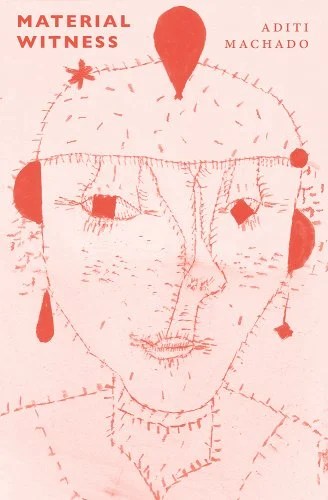

Her new collection, Material Witness, is short. It contains six poems, two of which take up more pages than their word count might suggest, because of Machado’s technique of spreading them out over many pages and working in different styles in each section, with sometimes just a single line per page.

I was excited to read this book when it came out because I really liked Machado’s earlier book, Some Beheadings. As I worked on this review, I came across an interview with Machado online in The Cincinnati Review, in which she says that earlier book came out of a frustration with poetry’s “lyric I.” And the poems in that book are obsessed with the frontiers of the self and the language that can be used at that frontier. For example:

A wind, a text.

A wind, a text.

The wind touches

to the skin textile.

Rayon, a cotton tag.

To be in public,

to feel private.

I am watched

& pleasured.

Grateful, I return.

This new book is a new front in this exploration. I looked up the meaning of “material witness,” and it seems to be a person who has knowledge of a criminal case. If you Google “material witness definition,” the sites mention that the witness’ information is so important or particular that the case can’t be decided without their testimony and the judge can require the witness to be present to testify in court, keeping them in a safe location if necessary, perhaps having them arrested. These details are important enough that they’re mentioned in all of these sources, even though the definitions are quite short. Is it a position of power to be a material witness, whose testimony is essential to the outcome? Or a position of weakness, whose knowledge can put you at risk and be taken by force? And what knowledge exactly do the subjects of Machado’s poems possess? What case is being decided? There may be an answer in this section of “Material Witness,” the first poem in the book:

You could have had visions, you could have had anything you wanted by except you couldn’t, not to the accountants, not to the heightened Then an opaque zone. Or darkness bled. Impossible to extract confessions The poem “Material Witness” uses the language of politics and history to describe what is happening to its central character, and yet politics and history are happening only to or within that character, without any of the usual context or referents that you might expect. “You discovered you were sovereign. You began to govern yourself by modes of wit.” And later, “Could it be you were divided into a body, politic? Could it be you’d assumed governance, subjection, rebellion, pastoral care, agrarian rites …” In this poem, Machado abandons the “I.” The poem is addressed relentlessly to a “you” in what seems like a distancing device—there is no indication that the “you” is a separate person who exists in relation to the poet or to anyone, that they have friends or lovers or relatives. Calling them “you” just allows the poet to comment on them. The distance between the poet and the “you” is so great that I found it difficult to connect, emotionally or imaginatively, to the content. This problem continued for me throughout the first several poems in the book. The second poem, “What Use,” begins, “To supplant the septum ring, it is rousing, it is a formal concern.” Machado got me to look up “supplant,” a word I already knew, in the dictionary, because I found her use of it so puzzling here. I appreciate her power to get me to do that. But it is a formal concern indeed, and no threats that the period will accelerate “into the eye like a gelatin bullet” make this poem feel affecting. She repeats, “It is what it is to be a formal concern.” The poem “Bent Record” uses the “I” with just as much ironic distance as the first poem uses the “you.” This “I” is a persona, an imperialist caricature who describes their own swashbuckling behavior with a winking tone. “It was I who ‘discovered’ the plant and I who named it imperially after my own self. Then I ironed out the language and I showed my work in the cruddy journals of the time.” Again, the ironic distance is so great that it’s hard to be moved by this poem, although the poem can be funny. But there were some moments of pleasurable shock, such as this line that I didn’t literally understand but found mysterious and beautiful: “I came to surmise on the porch of autumn with citrus discs and beads of solar attrition.” The collection deepens at its midpoint. My favorite poem is right in the middle and is called “Concerning Matters Culinary.” It seems to describe the courses on a tasting menu. This poem is written in all caps, but I did not replicate this in my quotations below because I thought it might be distracting in prose form. In the poem, this capitalization strikes me as another way of drawing attention to the words themselves and not letting us forget that the poem is a meal made out of written language, not out of food. Many poets would try to let the sensuality of the food speak for itself, but Machado puts adjectives in front of nearly everything. She insists on making language visible and being in charge of it, weirding the meanings of words and not allowing us to have a settled relationship with them. Machado’s language, in her poems, belongs to her, and she withholds and administers it to us in a one-way power relationship. Her adjective choices are sometimes straightforward. (“Candied gooseberry” makes sense. “Portly grapes” is accurate and charming.) Sometimes the choices draw attention to themselves. (“Trifling beef.” “Derelict kohlrabi.” Does this mean there wasn’t much beef and the kohlrabi was on the menu but not on the plate? Or are these food items with bad character?) The food, course by course and on the plate, is physically moving or transforming, and so is the poet. The seared tuna “sits cadmium” on sheets of guava, a scent of lime “evades detection,” the vinaigrettes “mediate,” “I ferment,” “apples sicken” (are they becoming sick, or are they sickening the customers?), “the fig rolls over,” salted juniper berries drop into a valley, and so on. The penultimate poem in the book, “Feeling Transcripts from the Outpost,” carries on some of this more relaxed feeling, less self-conscious about avoiding the lyric I and inhabiting its speaker’s feelings more fully. It is written in an unironic first person and makes explicit connections between election season and the cycles of a garden. The book ends with “Now,” a poem that echoes “Material Witness” in several ways—it is also addressed to “you,” and also spread out across many pages and written in different styles. Unlike “Material Witness,” which moves us through the poem day by day and through the progress of the character’s political awakening, “Now” takes a journey through a landscape, and uses imagery around plant and animal reproduction. I love the leg of our journey in “Now” that goes by train: now you take the train

you put on the hat & you drive the train

your hair pulses telegraphically

you have put on the exoskeleton of impure delight

pedicels fill upward into those umbels you call eyes

you drive to give the train its practice

you oil it, you move it in its happy ruin

you do this not for you—no, no

you do it for the bytheway foxes & the bytheway grasses, the bytheway inured to these the metals of their collective conscious

it is for them you collect the movements, for them you fill the umbels

& like so the train makes its rosaceous entry into the boomboom patch of nicotine grass

You may remember the words “pedicels” and “umbels” from science class, but I did not. The train imagery and even the sounds of the words made me imagine mechanical parts, but when I looked them up I found they were anatomical names for plant parts. That was the beginning of a frenzy of looking things up in this poem. Deckle. Thetic. There is pleasure in the words themselves, pleasure in the idea of giving the train its practice, pleasure in the leaping around of this poem that seems simultaneously associative and authoritative, like Machado is playing but also like she’s thought of everything already. This poem feels more sympathetic toward the “you,” more curious about the world it inhabits, more excitable. It ties together words and imagery from the rest of the collection—a fixation on light and on color; certain words, such as “radical” and “radish,” repeated from earlier poems. The main character’s body fat, which was sliced into in the first poem, melts into liquid here. The “you” in this poem may not be the same as the one we began with, but the similarities across these poems make them feel like partners, which, by opening and closing the book, complete a thought. And this final poem brings us along on its journey through the landscape, a journey that I will gladly take with Machado anywhere she is going. Material Witness, by Aditi Machado. Brooklyn, New York: Nightboat Books, October 2024. 80 pages. $17.95, paper. Ashley Honeysett’s debut book Fictions won the Miami University Press Novella Prize and was published in 2024. Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

methods of indiscretion increasingly purveyed in those final years in

which lyric was put before all, lyric tea, lyric grant, lyric mass shooter

give yourself up

scrutability of the land, heights you’d fall off of.

when they’re spilling already everywhere.

Then bloodless darkness. Dissent.

Trust nothing. The sun is president.