Zilka Joseph’s Sweet Malida focuses on a fascinating and little-known segment of Jewish history. Her topic is the Jewish community of her ancestors and of her immediate family. To learn of a group of travelers having survived as an intact sect within the vast populace of so vast a subcontinent as India, was, to me, akin to discovering a precious gem within a storied haystack. This story is revealed in Joseph’s new collection.

The collection centers around the Indian author’s family life with the Bene Israel, who resided in the area of Kolkata. Who were the Bene Israel, I wondered, and how did their community form? The author weaves the history of her community using several techniques: accounts of shipwrecks, descriptions of religious ceremonies, sacred family meals and recipes, and allusions to biblical events. Her work is not the typical form of poetry concerned chiefly with rhymes and other poetic elements. Rather, it is concentrated more in the telling of her family experiences and of her ancestral influences. As such, it’s more an historical account than a poetry collection; indeed, she calls it a collection of memories. (Her ancestors’ shipwreck may have occurred more than a thousand years ago.)

Joseph lived under a wide variety of influences, including her close acquaintance with Hindu, Muslim and Christian cultures, as well as her personal Jewish culture. The languages of Hindi, Marathi, and English shaped her thinking. As a young reader, devouring her British Ladybooks, she even encountered such Western folk figures as Santa Claus, among others. As daughter of a marine engineer who took his family to Scotland and England, and as wife of a man who emigrated with her to the U.S., these Western influences came into her Eastern experience as one might supplement a dish by adding more spices. Spice, in fact, is one of the prominent and literal elements in her writings.

Her opening poem “Eliyahoo Hanabi” is a depiction of a Malida ceremony honoring the Prophet Elijah, a figure treasured by the Bene Israel. The poem opens with a chant of praise to Elijah, and brings dried fruits, spices, the scent of rose petals into its lines so that we can almost taste, hear, and smell the celebration. It describes fiery Elijah in his chariot, and it revisits a worship site in Alibaug, “the soil / our wandering ancestors were / blown onto by the storm.” It is a fitting portal into the collection:

O Elijah, can you taste

the nutmeg, the cardamom, the freshly

sliced mangoes, guava, chikoo, apples and

bananas arranged like garlands? Can you see

the pomegranate seeds dotting the top

of the rice, bursting sweet juice

and tartness? Can you smell

the red rose petals

scattered everywhere,

the cups of cloves?

“We knew the shema,” Joseph writes in her “Choral Sonnet;” where she delves further into her history and explains how “Christians discovered us. Later / they taught us Hebrew, translated holy / books to Marathi, educated us, / but could not convert us.” Her poem mentions the Cohanim gene, and she refers to blood tests that link the DNA of the Bene Israel to that of the blood of Aaron, brother of biblical Moses. (A reference appearing at the back of the book links to a document supporting this claim.) Cohanim is Hebrew for “priest,” and refers specifically to the Aaronic priesthood. “Did we need anything to define us?” the poet asks. “Let the world scoff at the Cohanim gene / found in our blood. We always knew the truth.”

Josephs presents her memories in numerous of ways—as prose poems, as poems sometimes in broken lines set into two columns (as in “The Angels of Konkan”), sometimes as couplets with intermittent single lines running through as call-and-response echoes, sometimes as simple nostalgic stories (given in prose form) describing family meals or cooking experiences shared with her grandmother.

Her tribe were known as oil pressers; they were called “Shanwar telis” (Saturday Oil Pressers, i.e., those who do not work on the Sabbath.) In “Not One Fish” Joseph speaks about her “mysterious community, so apart from the urban world.” They didn’t refer to themselves as Jewish, because they didn’t know the proper noun. However, a visitor who came to them, around the year 1700 may have helped them revive their Jewish identity. The visitor asked for a feast of fish. In “Not One Fish” Joseph tells how they brought him paplet, bangda, and tarli, all fine scaled fishes, but not one crustacean. Joseph writes:

He knew then: they kept kosher,

a word they did not recall,

just kept a simple faith

in the God of Abraham.

Joseph’s account of the blessing of manna, in “Man hu? Man hu?” is expertly done. It refers to the discovery of hoar frost on the ground, as recorded in the Book of Exodus:

Man hu? Man hu?—

they asked in Aramaic—

what is it? What is it?

She calls the manna “jewels harvested before sun-up.” She writes:

A “form of dew” that “hardens

and assumes the form of a grain” …

Following so appropriately after “Man hu? Man hu?” is her account titled “What Ravens Do.” This offers her record of the biblical flood, and of the olive twig as the symbol of peace, carried in the beak of the dove. She writes:

Was

it not the

wild ravens

that Elohim

and meat, morning

commanded

and night,

to deliver bread

dawn and dusk

to Elijah

by a brook

at the edge

of Jordan?

Joseph assimilates the ancient story into her own poetic voice—the “poem” itself traverses a long stretch of biblical history from Noah to the prophet Elijah.

The author’s poetry, as mentioned, appears in a variety of forms—sometimes across the page, as prose, sometimes in broken lines set in two columns (as at “The Angels of Konkan”), sometimes in couplets with intermittent single lines running as call-response echoes. “Prophet of the Rock,” scintillates with its “magnificent horses,” its “blazing orb,” and its spewing “fire hooves clashed on stone.”)

“Kaulee Haddi” is one of several poems in which Joseph presents the foods they ate, generally a fusion of Indian and Jewish styles. Of her father eating the chicken curry, in “Kaulee Haddi,” she writes:

drunk with masala—

ginger warm, garlic sharp,

coriander mellow. But he rarely

ate it, breaking off that kaulee tip

with his wiry engineer fingers

salty with memories

//

we watched him bend,

melt the hard beaten bones

of his tough maritime heart.

Joseph describes Sharbath and other Jewish rites in “My Cup Runneth Over.” She tells about making sharbath in the U.S. where she has emigrated, attempting to mirror the way her mother performed the rite years ago:

In Keats’ poem, the figure of Autumn watches the winnowing of grain and the pressing of apples as she sits in a field or shed. I, too, was a witness—to the making of our simple sharbath. Hannah, my grandmother, was the real head of the house when I was small.

Her memory carries her back:

I am a small child. It is Kolkata in the late 1960s. I would get in the way, trip my silver-haired grandmother up by getting entangled in her sari, but she would never shoo me away. The dusty raisins … were obsessively picked over, de-stemmed, washed thoroughly and soaked in water … Covered and left to soak in the corner of the kitchen. Like bread, it sat to brood, but instead of rising like a cloud, the raisins plumped, turned as fat as the seven fat cows that good old Joseph the Dreamer saw in his vision …

A favorite poem from the collection is “Leaf Boat.” Here Joseph imagines herself a being floating as a leaf-boat lamp in the Hooghly River of West Bengal. The nets of the boat drag into brown silt, the boat is moored to trees. The unsleeping captain is the third eye:

braved thunder fire flood

slaved in the engine room

never sleeping when the storm hit

his commands whip through the darkness

Goddesses enter her fantasy. She also imagines her mother weeping over the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. The fishermen have locked their torches on the deck and gone below.:

the boat rocks and tilts

the hurricane lantern shakes

tiger claws break through wood

The passages mirror her ancestors’ shipwreck on the shores of India. They are expressions of the pain that happens when people cross into new worlds and cultures. When there are storms, upturns, and separations, transformations happen; they must be resisted or somehow absorbed. Sweet Malida is Joseph’s fine artistic expression of a life’s unfolding, assimilation, and transformation.

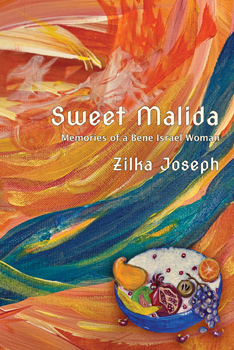

Sweet Malida, by Zilka Joseph. Mayapple Press, 2024. 66 pages. $19.95, paper.

Carole Mertz is the author of Toward a Peeping Sunrise, a poetry chapbook (Prolific Press), and Color and Line, a full-length collection inspired mostly by ekphrasis. Her recent reviews will appear December, 2024, at Dreamers Creative Writing, Mom Egg Review, Oyster River Pages, and World Literature Today. Carole writes in Parma, Ohio, where she lives with her husband in Ukrainian Village. Her craft essay about critiquing is forthcoming at Working Writers. More: carolemertz.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.