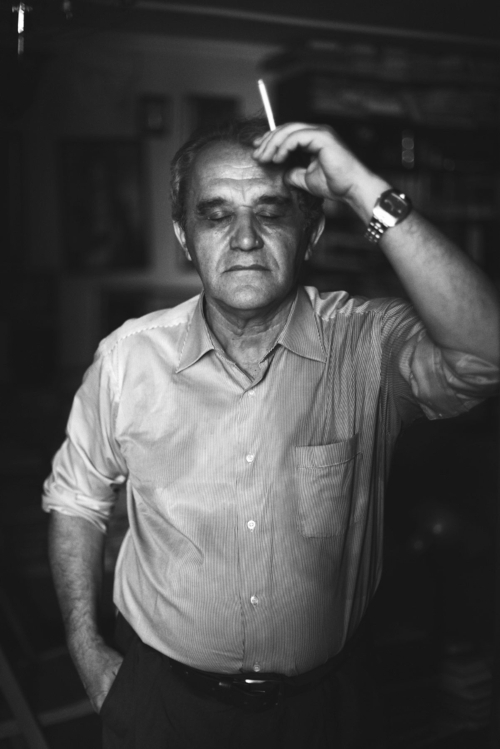

Born in Durrës in 1949, Moikom Zeqo was considered one of Albania’s very most important writers and public intellectuals. (When I visited Zeqo in Tirana in 2019, we couldn’t walk more than a couple blocks without a stranger stopping us to pay respects.) In 1974, Zeqo’s writing was suppressed for incorporating free verse and surrealism, and for criticizing Albania’s cultural and political isolation. During his decade of literary suppression Zeqo reinvented himself as an archeologist with a specialty in underwater archeology. In 1991, as the communist system was collapsing, Zeqo was appointed Albania’s Minister of Culture, and from 1992–1996 he served as a member of Albania’s Parliament. From 1998–2004, he directed the National Historical Museum in Tirana, after which he worked as a freelance writer. Though Zeqo wasn’t personally religious, his ethnoreligious background was Bektashi—a relatively obscure suborder of Sufism founded in Anatolia and for the past hundred years headquartered in Albania. In 2019, Zeqo was named a “Knight of the Order of Skanderbeg,” which is the highest honor an Albanian civilian can receive. By the time of his death in 2020, he had published 100 books.

Franz Kafka, Bucephalus, and Alexander the Great

In his room in Kierling Sanatorium, on the anguished evening of March 27, 1923, Franz Kafka coughed a spritz of blood into the handkerchief he’d brought to his pale lips.

An absolute, dispirited loneliness filled the room, which smelled ferociously of pharmaceuticals.

Kafka was drenched in a cold sweat and consumed by Sisyphean exhaustion—but he could still focus his attention on that bloody handkerchief, in which tubercular bacteria invisibly embodied his impending death.

“Death frees you from illusions,” Kafka thought. “Death is a miracle, higher than any doctor.”

After a while he slipped into sleep, as if into an abyss.

He fell, flew, rose up. He’d been carried off by a yellow hurricane. A cancerous comet crashed against his face. Spherical beings and triangles covered in blue thorns were off somewhere singing a merciless and meaningless Gregorian chant.

A rabbi with the head of Zeus’ eagle drove his copper beak into Kafka’s chest. (Kafka could feel worms moving around hideously in his torn-open lungs.)

A completely empty space—one entirely free from the tyranny of gravity—flashed before him.

He cried out in his sleep.

In the morning, he felt like a sterile corpse—but his brain was alive, incandescent.

Two days later, surprisingly, he seemed to recover a bit.

He could feel the silhouettes of doctors and nurses moving in and out of the room, only semi-formed, as if he were glimpsing them through frosted glass. Their restrained, pitiless gestures were both serious and heavy, like the movements of prison guards—though they were clothed in purgatorial white uniforms.

It was in this persistently hazy condition, full of delicate and ephemeral hallucinations, that Franz Kafka fell asleep again—at which point the core of his consciousness, besieged by catastrophe and wild oblivion, became entangled with a very ancient subject.

In fact, this subject was the genesis of many subjects. The 333 names of Satan according to Talmudic doctrine appeared to him. I don’t know why, but flowers that smelled like wounds and clotted blood shook loose from them, as did letters sent to him by Dora Diamant and letters sent by Milena—that other woman he had loved, Dora’s worthy rival. (He didn’t want to, he didn’t dare, recall breaking off his engagement with Dora.) Then a knotted dreamscape opened before him: Babylonian palaces appeared, followed by Alexander the Great of Macedonia and his horse Bucephalus—who spoke in a harsh, merciless human voice of massacring captives along with the rest of the defeated.

On his fifth day in the sanatorium, Kafka was visited by his friend Max Brod, who burst into the hospital room without warning.

Brod’s eyes were full of both grief and unbearable admiration.

Caught off guard by his visitor, Kafka managed to say with difficulty, “My dear Max—as you know, I’ve written a short novel that—thank goodness!—will never be published: The Trial. You possess the manuscript, and now my dying wish is that you burn it. Don’t let it be published! Please—you must burn it. Burn all my manuscripts and letters. I know you’ll do this. Please, don’t disappoint me.”

Max smiled distantly.

Kafka continued, “Now let me tell you what’s been tormenting me. Literature, I now realize, is merely a public neurosis.

“In some obscure place—some geographical enigma between East and West—a strange thing has happened. The citizens of this small state have come to understand that a horse—Dr. Bucephalus—will become their judge.

“Both imposing and innocent-looking, he no longer looks like Alexander the Great’s battle horse.

“In addition to Macedonian and Greek (the second of which Aristotle helped Alexander linguistically refine), he also knows Illyrian—that language of those incomprehensible barbarians who lived in accordance with strict, ineradicable vices—as well as the artificial and ambiguous languages of the Thracian and Phoenician oracles.

“Bucephalus, both serious and humble, will move with briskness, delicacy, and majesty through the gates of the Courthouse.

“The doorman, with the tired look of an old stable keeper, will be filled with wonder when he sees this young judge ascending the building’s long stairs. The marble will echo fearfully beneath his horseshoes.

“Overall, the civil servants and the State Bar Association will welcome the arrival of Bucephalus.

“In today’s social order, many legal theorists have ended up killing themselves. Or else they’ve gone mad.

“Our situation is explosive; the crisis is universal. Bucephalus—if only because his name is famous in world history—deserves a welcome reception.

“It’s clear that today there are no more Alexander the Greats. And without his horse to carry him, he wouldn’t have been able to walk to within a centimeter of greatness or glory.

“History should be written by the horses. Their riders have unjustly appropriated the entire narrative. All the riders know how to do is kill. Seated at a banquet table, they feel a sudden urge to throw a spear into the chest of a friend—and so they do it without thought or any erosion of conscience.

“They think the State is too limiting, and for this they curse the dead of five hundred years ago.

“No one, no one, can lead them to mythic India because Alexander is dead—having been cursed by this useless, debilitating fantasy.

“Since the time of Alexander, the gates of India have been an unreachable utopia—but kings’ swords have kept pointing in their direction, in the direction of a dream suffused with tragic twilight. Today the gates have moved beyond infinity, and even their shattered, blown-apart pieces spin and spin without ever finding peace or rest.

“So many people carry swords, ready to kill each other—all they can see are the skulls of perpetual enemies.

“In the end (whatever that is) Bucephalus will need to dig deep into the books of justice. Redeemed by peaceful lamplight—his loins freed from his rider’s thighs and saddle, far from the rumblings of Alexander’s battles—he’ll turn the pages of thick, old books . . . . When he condemns, he’ll ignore the books entirely and simply neigh . . .”

Kafka’s forehead was drenched with sweat—as if he’d just narrated all of history to reveal the very core of the universe.

Brod smiled dully, utterly confused. He looked like he might faint. He didn’t know what to say to his friend, who was clearly dying.

“Oh—” muttered Kafka, becoming more subdued, “don’t ascribe too much importance to this stupid parable.

“Centuries later, a Roman emperor . . . Caligula . . . or someone else . . . who cares . . . made his horse a Roman senator in a grand ceremony . . . in the somber, dignified Senate . . .”

Months passed.

Kafka wrote a bit—or, rather, he scribbled grotesque little motifs in his diary.

In 1924, around midnight during a storm, he slipped again into the abyss of a dream, which soon became a coma.

Fingers with the heads of snakes at their tips pointed to the date.

Kafka felt like he was about to vomit in great convulsions.

He understood that an invisible supreme judge somewhere in the heavens—or in the volcanic depths of the anonymous earth—would soon utter with a scowl, You are guilty, guilty, guilty . . .

Then the neighing of Bucephalus—whose mane was now the wig of a judge—enveloped him in ashy chaos, absurd and full of perpetual anguish.

1989

Translated from the Albanian by Epidamn Zeqo & Wayne Miller

Time, Space, Death

The naïve but eager dervish Sari Ismail was standing beside Haji Bektash Veli.1

Ismail had seen with his own eyes the regular miracles of his Pir2—for example, when Haji Bektash kicked his heels into a boulder as though it were made of dough, winning a challenge with Pir Rufi. Rufi had been riding a wild and enormous lion when immortal Haji Bektash said: “Sure, you can ride a lion—a living creature—but can you ride a rock, which doesn’t have a soul?” Haji Bektash then climbed onto a massive stone, and, when it had been properly compelled, the stone began to move so Haji Bektash could ride it, outstripping his brave opponent.

This was clearly an astonishing feat. But could Pir Haji Bektash control time itself? Time is the most elusive and most powerful thing, the dervish thought. No one can challenge or grapple with time.

One day the dervish and his Pir were invited to a feast. Some hunters had killed a deer with royal antlers. As the sun was setting on the horizon, they lit a fire to roast the animal. The great Pir butchered the deer himself, skinning it and hanging the body from a tree branch to drain the blood.

Suddenly glowing lights appeared on distant Karaca Dağ Mountain. Haji Bektash saw them and said to Ismail, “Those lights have been lit by the Erenlers,3 who want me to meet up with them. Come with me!”

They left as night fell, and soon they were walking through blackness. Then the sun rose and they walked another full day, sweating, but they still hadn’t arrived. In the end, it took them three days and three nights to arrive at Karaca Dağ.

There the two men encountered the Erenlers.

They all greeted one another, sat down, and began to talk. Erenlers look basically the same as people, but they’re translucent because they’ve been dead for a long time.

But unlike the ordinary dead, Erenlers can eat and drink. So the group carried on a divine feast for almost three years. At last, they were finished. They said their farewells and left.

When the dervish and his Pir returned to the hunters, the hunters asked, “Why did you come back so soon? When you left, the sun was setting—almost touching the horizon—and just now the evening’s begun. The blood has drained from the deer, and we’re ready to roast it for dinner.”

The dervish wanted to say they’d been gone for three years, but he said nothing. He realized now that his master could manipulate and organize time however he wished.

•

What about space? Could he manipulate space as he’d manipulated time?

It was as though Haji Bektash could read the dervish’s thoughts.

He said, “Put you right foot on my right foot.” In the blink of an eye Sari Ismail found himself in Palestine. He was astonished. He picked a few fresh dates from a palm tree. How did I come all the way here? he thought. A caravan of camels passed by. He begged the travelers to let him join them, which they did. After seven days, the group arrived in Mecca, where they prayed. When they were finished praying, Sari Ismail had a sudden vision of Pir Haji Bektash, who said to him, “Put your right foot on my right foot.”

In a flash, Ismail found himself awake and standing beside Haji Bektash, who was conversing with some villagers. Haji Bektash said to the baffled dervish, “Dervish, we’re hungry. Could you give us some of those dates you’re carrying?”

Sari Ismail passed around the fresh dates, which everyone enjoyed like never before.

•

What about death? Isn’t death the most absolute expression of power? The most terrible?

Ten years after Haji Bektash’s death, Sari Ismail erected in the city of Brusa a magnificent shrine to honor the “Pir of Pirs,” great Haji Bektash Veli.

Ismail hired a renowned master builder to design the project, dig the foundation, carve the stones, and erect the shrine. When the builder was at work on finishing the dome, he suddenly felt impossibly thirsty. “Water, water,” he cried out—at which point his foot slipped and he fell off the scaffold.

Everyone was amazed.

As the builder fell, a glass of fresh water appeared in his hand, and he landed on his feet without the slightest injury. Not a drop of water spilled from the glass.

The glass had been handed to him by Haji Bektash, who’d instantly appeared and disappeared.

From what source had the glass been filled? With what divine water from the worlds above, unknown to ordinary men? From what life inside the invisible realm of death?

Durrës, 1998

Translated from the Albanian by Kleitia Zeqo & Wayne Miller

Eyes and Art

Antiquity is blind. The eyes of its statues have no pupils. Its muscled bodies are perfectly sculpted, but the eyes are white spheres, completely absent. This makes ancient art more external than internal. Pagan mythical deities are sightless—made only to be seen by the living. Their eyes are false. They are not eyes.

(Medusa’s eyes, however, turn everything to stone, because paradox is relentless!)

Byzantine art is the art of eyes. Eyes express the spirit. An art of eyes is internal, not external. All the eyes of Onufri’s4saints have pupils and irises—like mysterious flowers pressed under glass.

The ophanim—those apocalyptic wheels full of eyes—are the apotheosis of multi-eyed beings. Eyes independent of bodies. Eyes removed from their dull and vulgar faces.

Maybe the skulls of the dead are eyeless because the eyes have traveled with their souls to the kingdom of eyes—where eyes never close and see absolutely everything.

When Saint Paul says in his First Letter to the Corinthians, “For now we see a blurred image in a mirror,” he warns us not to absolutize our eyes. It’s well known that the human eye can’t perceive ultraviolet rays—whereas the absolute, merciless gaze of God is inescapable. The inventions of the microscope and the telescope prove the limitations of our eyes—reveal us to be brazen and arrogant, both ever-seeking and endlessly lazy.

Moses saw God in the form of a bush that burned but was never consumed. When Moses descended barefoot from Mount Tabor, his face shone with an inner light. A divine, golden mask had replaced his regular face.

God cannot be seen from the front, only from behind—as it says in the Old Testament. Thus, God is a taboo for both sinners and prophets.

God made Man in his own image, but no man in the world is God. God is an empty form—but not without content. The form repeats. The content is endless, and impenetrable.

1998

Translated from the Albanian by Wayne Miller

In Porto Palermo

Years ago, I visited the castle at Porto Palermo on the southern coast of Albania. I had taken my scuba gear and air tanks, so I made an exploratory dive—which wasn’t entirely without risk in those waters.

I surfaced, full of sadness, holding the broken mouth of a Hellenistic amphora. The seabed there was littered with broken bits of amphorae—a shipwreck from many centuries ago.

The amphorae had been shattered by illegal dynamite fishing. The dynamite throwers had had no idea an ancient shipwreck lay hidden under the surface.

The destruction of that ship and its history by means of modern explosives was spiritually crushing.

When I came ashore, I was muttering something that must have sounded surreal.

It’s true that the terrible tendency to turn reality into oneiric subject matter—to metamorphose the world—is a powerful one.

I might say I’ve benefited from this tendency, but perhaps I’ve also been seriously harmed. One’s intellectual gifts are never purely assets.

Inside any gift is an immediate—sometimes secret—threat of disaster, loss, or destruction.

But balance, that transparent wire—that dividing and joining line of worlds, of paradoxes, of hopes and fears, of creation, emptiness, youth and animality—is, in the end, our shared salvation.

Our gifts are so individual—why aren’t we suspicious of them?

I’ll never forget that lost moment beneath the blazing sun and Porto Palermo Castle.

It’s not often that the work of individual men and the work of a nation become embalmed by saltwater, then destroyed via dynamite by men who know nothing of the destruction they’ve caused.

I recall the history of Porto Palermo Castle, built by Ali Pasha of Tepelena. Not far away lies the church where awful 80-year-old Pasha was married to wonderful 14-year-old Vassiliki Kontaxi. Vassiliki, with steadfast conviction, had asked her pallid and graying betrothed for a Christian wedding.

Pasha smiled and, incredibly, complied.

The church was deserted—abandoned. Pasha ordered a priest be found. Eventually his ghost-like knights dragged one in, lit candles, and thus at the stone altar the ceremony began.

Above the apse hung a cross with a sculpture of Christ. The terrified priest uttered the ceremonial formulas, then announced the union of this 80-year-old and 14-year-old.

Pasha turned his back to the priest. Holding his bride by the hand with what almost appeared to be compassion, and while still inside the door of the church, without even turning his head, he pulled out a flintlock pistol, pointed it into the air behind him, and fired, shattering the cross and its stone figure.

No one knows why he did this.

Was it just a whim, or was it an expression of his supreme power? Was it intentional blasphemy, or just the anarchic carelessness of Pasha’s actions and thoughts?

Who can solve this riddle accurately or completely? No one.

This historical example is provocative. Don’t books contain similar explorations and weavings of paradoxes? Don’t we construct for ourselves multiple psychological universes that present within the world new zodiacs—and then with exterminating self-irony they cause us to be sealed away and pulverized into dust.

Aren’t conversations like that? Without conversations, could our lives be vulgar or sublime or even mundane?

Is there any difference between Pasha’s impetuous pistol bullet and the thrown dynamite of those narrow-minded fishermen near the shore of Porto Palermo?

Who can know the full extent of our devastation, both internal and external?

Can we even begin to imagine Atlantis, with its broken temples and sculptures thousands of feet below the surface of the sea?

1994

Translated from the Albanian by Wayne Miller

The Resurrection of Onufri5

In a cave he had covered with frescos, the painter Onufri, old as a patriarch, could feel his death was close.

The cave was in the Shpat Mountains, in a region where Onufri had once written manuscripts of poetry and filled churches with his art.

He’d decided to spend his remaining days in this cave as an ascetic.

Through the cave’s mouth, he could see the twilit world shining magnificently like some impossible painting, one that could only be the work of a mysterious god.

Weakened and exhausted, the sweat of death covering his forehead, Onufri was experiencing the end—his insuperable futility, his nothingness, his inevitable dissolution, his body as dust, to be dispersed forever by a nameless wind.

Long ago, he had been able to move his hands such that the people had called them “lions of color.”

He had made a thousand paintings with those hands.

How did I ever manage to paint Jesus on the cross?

In these same Shpat Mountain, Ottoman invaders had cut off the heads of captured Albanian revolutionaries and nailed their bodies to poles.

Years ago, Onufri had collected fifty human skulls, which he’d kept in his workshop. His students were initially shaken, but eventually they got used to them—just like the Illyrian ascetic Saint Jerome, who in the 4th century lived surrounded by skulls in a cave in Bethlehem while he translated the Bible into Latin.

How is it possible I painted that fresco of David? Was I actually imagining Skanderbeg?6

Did I combine their faces into one?

From the cave, Onufri could see the moon in the sky like the halo of an absent head—of a god that maybe never existed.

But there were so many gods!

Did it even make sense that the only true god was the Sabaoth God Jehovah?

Onufri was scaring himself with these thoughts. This was dangerous heresy—though mostly, in that moment, he felt only indifference and hopelessness.

I’ve believed in my art. Art has been my religion. What else can there be beyond that? Only death, obliviousness, emptiness, silence—the disintegration of everything.

I’m dying. This is my inescapable end.

Onufri closed his eyes.

Then he opened them again.

Why, when he was nailed to the cross and suffused with pain, did Jesus suddenly cry out, “Eli Eli! Lama sabachthani?”

Why? Who was he lamenting to?

What was the purpose of his protest?

Onufri bowed his heavy head.

Maybe the name Onufri would never be spoken again.

Just then, he was suddenly overcome by an incomprehensible elation. A miracle of the senses arrived out of nowhere to fill his body just as his life was abandoning it—just as it was balanced on its last moment.

Shepherds appeared in the cave playing flutes, which were like cobalt crescents in their hands. Then a corpse arrived, unwrapping the dressings from its body.

Then three horsemen. One of them was Saint George, slayer of the dragon.

Riding on the back of Saint George’s horse was a little boy. He looked like Gishto from Albanian folklore—but it was the prince of Crete who’d been kidnapped by Arabian pirates, then rescued by Saint George.

He greeted Onufri joyfully.

Then—hazy at first—a cradle appeared in the middle of the straw, a donkey and bull beside it. The cradle was empty, yet it glowed with a blinding, internal light.

Onufri felt an agonizing pain.

He began to shrink—then he hunched over into himself and started to transform.

His beard, his long gray hair, his wrinkles and abominable old age, the asphyxiation of his dead lung and the mysterious impotence of pre-death all faded away.

Onufri had become a baby.

He lay down inside the glowing cradle.

He had been born.

Reborn.

From the stars, from the comets of the cosmos, men on the backs of eagle-winged horses were charging at great speed.

The earth split, and ancient statues from the most distant past rose up from the depths. They sailed toward Onufri on angel’s wings.

The music of that flute had enraptured everything.

3 June 1990

Translated from the Albanian by Loredana Mihani & by Wayne Miller

Wayne Miller is the author of six poetry collections—most recently The End of Childhood (Milkweed, 2025) and We the Jury (2021). His awards include the UNT Rilke Prize, two Colorado Book Awards, a Pushcart Prize, an NEA Translation Fellowship, six individual awards from the Poetry Society of America, and a Fulbright Distinguished Scholarship to Northern Ireland. He has co-translated two of Zeqo’s poetry collections—Zodiac (Zephyr, 2015), which was shortlisted for the PEN Center USA Award in Translation, and I Don’t Believe in Ghosts: Poems from Meduza (BOA, 2007)—and he has co-edited three books, including Literary Publishing in the Twenty-First Century (Milkweed, 2016) and New European Poets (Graywolf, 2008). He co-directs the Unsung Masters Series, teaches at the University of Colorado Denver, and edits Copper Nickel.

Kleitia Zeqo, Moikom Zeqo’s daughter, lives in Amsterdam and works as a consultant in the fields of science, technology, and innovation (STI) and cultural policy for the European Commission. She holds degrees from Royal Holloway and the London School of Economics.

Loredana Mihani is pursuing a PhD in the Department of English Studies at the University of Graz in Austria.

Epidamn Zeqo, Moikom Zeqo’s son, lives in the Santa Cruz Mountains in California. He holds degrees from the London School of Economics and the University of St. Andrews and is pursuing a PhD in history at the European University of Tirana.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

- Haji Bektash Veli (1209–1271), founding figure of Islamic Bektashism and Alevism. In narratives about Haji Bektash Veli, Sari Ismail is often depicted as his disciple. ↩︎

- One of the Imamic ranks in Bektashism, “Pir” means “elder.” ↩︎

- In Bektashi tradition, Erenlers are the spirits of dead saints. ↩︎

- Onufri: famous 16th century Albanian painter of icons, and an Orthodox Archpriest in the city of Elbasan. ↩︎

- Onufri: 16th century Albanian painter of icons, and an Orthodox Archpriest in the city of Elbasan. He is one of Zeqo’s favorite artists. ↩︎

- Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg (1405–68), Albanian national hero who resisted the Ottoman Empire. ↩︎