Not quite equal parts nonfiction and fiction, the stories in Honky show the life of a young man growing up white and poor in rural “Northernass Wisconsin” who then moves to “Southernass Georgia” as an adult. His enthusiasm for spaces that, in the years he was growing up, were closely associated with Black culture—basketball and hip hop—get him taunted and bullied, giving him a varied view of racism’s effects. His efforts to fit in mix bravado with pathos, something akin to yelling an apology at someone you didn’t want to know you cared for. By the time he is an adult in Georgia, married and teaching, his past experiences compel him to try to do right by his neighbors even as he still stumbles to find his place.

In these linked stories, the narrator simultaneously tells the story frankly and employs meta-narrative devices—addressing us directly, particularly when wading into issues of race and representation. The author and the narrator (the same person, except when they’re not—good luck parsing that) want us to know that they recognize that the statements or attitudes are retrograde or problematic, even if the context of the initial time or the encounter itself were circumstances during which the ideas weren’t a problem—or at least not understood or experienced as such. The book often balances realism about the simmering micro-conflicts of racial negotiation with something akin to apology. About halfway through the book, we want to say, it’s OK, Ben. We get it.

Honky is absorbing. Watching the slow-motion brick shot of Drevlow’s youth is to both shake your head and to end up rooting for some sort of victory—whether over the domineering father who disrespects, as only Boomer dads can, the interests of his son or to hope young Ben gets a leg up on a hotshot mess of a college basketball star that the diminutive Drevlow has the challenge of coaching. In “Terry Cummings,” Drevlow earns a key Pyrrhic victory, nearly losing an eye in the process, and it helps the momentum of the first half of the book shift from something that felt unrelenting. Here was redemption. Revenge. Even joy—along with injury. In the stories of Honky, any happiness comes at a cost.

Honky highlights some familiar ground about the disenfranchised sharing quarters. Echoing the classic Tom Hanks appearance SNL’s “Black Jeopardy” just before the election of the human diaper stain in 2016, Drevlow and his Black compadres spar for the last scraps from the table at which they all are denied a seat. Basketball is the means of combat and hip hop their expression, but they all share in the misery of compromised circumstances.

In an interview with Adam Van Winkle at Cowboy Jamboree Magazine, Drevlow said in 2023 that “most everything I write is maybe 85% true.” The reference is mostly to how the events play out in his work—the emotional urgency and internal conflict, even if not exact in its truth, achieves the feel of Truth. As Drevlow says in the first story, “Dad: Act I”: “I have nothing but stories to tell you, some of them true, the stories you’ll never hear from anybody but me.” We are invited to an intimately thoughtful place, one reflecting on mayhem.

In “Tyra Banks,” the narrator falls asleep masturbating and leaves a space heater running. When he awakens late and runs off to school, the space heater starts a fire that burns the house down. For Ben, “my mom would never have it in her to blame me for burning the house down with my careless masturbating.” He is a younger brother who lost the older to suicide, and his father is all about Lutheran faith, and so the stew of religion, repression, race and sexuality is of course cleansed in fire. But it isn’t—it’s just the beginning.

In “Boykin,” a story about “the only black kid I know growing up,” Drevlow is witness to the boy’s struggle to be himself around the condescension of white teammates, the coach, and the school. Boykin is the only kid who goes to the funeral for Drevlow’s brother. Boykin’s tragedy is telegraphed through the story and, sure enough, one slur too many during a basketball game and Boykin tries to hit another player. Drevlow pulls him away, “hugging Boykin the way guys like us only feel comfortable hugging other guys—when it’s under the threat of violence.” Boykin leaves school not long afterward and is never heard from again.

People do not leave their roles in Drevlow’s stories, and those roles create numerous unresolved conflicts that move the book along. They don’t grow and the narrator understands this in retrospect, even if the present tense gives the stories an urgency that makes it possible to forget—for a moment—that the narrator is recalling, and that there is little opportunity for growth without being smacked back into place. Such a smack happens at the dramatic height of the first part of the book, “Terry Cummings,” when assistant coach and former scrub player Drevlow endures the abuse of a diva player until one day he bests him on the court, drilling threes that Cummings cannot stop. Cummings, in frustration, leaps at Drevlow and nearly takes out his eye.

For the second half of the book, Drevlow is in Southernass Georgia for his “future ex-wife’s job and we’re living next to a Christ Science church.” Among the travails there are unhoused persons sleeping outside the church, part of a tableaux of moral dilemmas—privilege next to homelessness, angst over the fact that his T-shirt is still called a “wife-beater,” that he is essentially a feckless husband of a sugar mama who “hasn’t laughed at anything I’ve said since we moved down to Southernass Georgia” and whose enthusiasm for books about World War II means she is “a woman who has to turn to Hitler to put her mind to rest. How sad is that?”

Throughout the collection, Drevlow nurtures these neuroses about privilege and whiteness, careening from concern about the fact that his rescue dogs—a Greatest Hits of attack breeds including German Shepherd, Pitbull, and another breed that’s part Dalmatian—were abused and raised to attack and menace Black men over to stating that despite his donating to the NAACP he’s a tepid ally. But this narrator has even more to think about, navigating the grit left from a grinding childhood of neglect and inadequacy and now an adulthood where fitting in is elusive and fraught. Perhaps that’s why geography is how the book is divided—for despite moving from the rural north to a mildly more cosmopolitan south, and with all the burden of southern history (see C. Vann Woodward) spreading itself well beyond and, particularly, above the Mason Dixon Line, the sticky residue of racial legacies create the conflicts of the story, and lead to choices questionable and otherwise. That Drevlow’s narrator is funny and self-deprecating while also concerned that he can do right by people (however fecklessly) lets him get away with some disastrous behavior.

As a collection, Honky has the momentum and drama that comes from a car wreck you see about to happen. Unlike the car wreck, it carries us past the collision to see the waves of impact reverberate through a life.

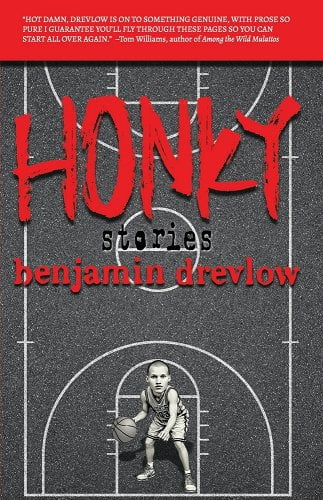

Honky, by Benjamin Drevlow. Cowboy Jamboree Press, August 2024. 196 pages. $14.99, paper.

Gabriel Welsch is the author of a collection of short stories, Groundscratchers, and four collections of poems, the latest of which is The Four Horsepersons of a Disappointing Apocalypse. Recent work appears in Southern Humanities Review, Pembroke Magazine, Chautauqua, Emerald City, Pithead Chapel, Cloubank, and Novus Literary Review, among others. He lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with his family, and works at Duquesne University.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.