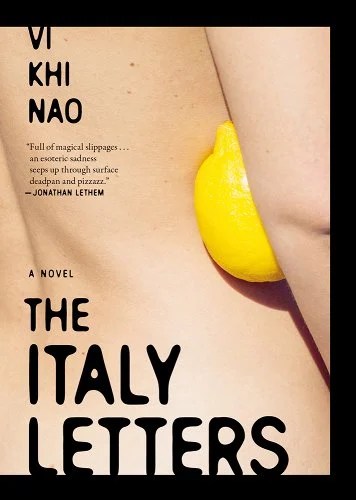

The epistolary form has been standard in literary fiction more or less since its inception. We’ve seen it done well and originally in authors like Ovid and Samuel Richardson, cleverly reimagined by folks like Mariama Ba, Julie Schumacher, Roberto Bolano, and Calvin Kasulke. In fact, I’ve seen it done so well, and in so many iterations, it’s easy to wonder if a person can really do anything original with the epistolary form. Vi Khi Nao’s newest novel, The Italy Letters, I would argue, does just that—it quietly, calmly pushes the form in a new direction.

Let me start with my best attempt at an analogy to help explain what is so brilliant about this small book. There are those rock and roll guitarists who stand up at the front of the stage as they power through some epic solo, fingers moving all over the fretboard, sweat everywhere, glistening in the spotlight, ready for you to be wowed. I’ve seen them—and been wowed. But then I’ve also seen a jazz pianist do the near-impossible at the back of the stage, not soloing but just supporting the music, being impressive in ways that only those attentive or lucky enough (I was the latter) might notice.

For many years of my life, I was impressed by guitar-solo literature, texts whose pyrotechnic writing—in-jokes, meta-everything, intentional difficulty, complex allusions and self-referentiality, genre defying, unreliable narrators, and constant winks to the audience—let us see the author is impressive, and in fact really wants us to stand in awe. Nao, in The Italy Letters, is more like the aforementioned jazz pianist. She has many of the same moves—the writing chops in this book are honestly off the charts—but she isn’t doing it to show off, and the artistry can be easily missed. Here character and story come first, and the artistry is in support of telling the narrator’s story rather than winking at you while the metaphorical author-as-guitar-soloist drags on. In other words, and to sound as old as I actually am, the form and content work in harmony in a way that quietly wowed me.

At its core, The Italy Letters are letters from an unnamed woman to the woman she loves. The protagonist lives in the US—writing from various locales within the continental United States—where she is overwhelmed with a sick and suicidal mother for whom she is caretaker, lack of money, the quiet racism within outwardly liberal universities, the need to publish more, and, most importantly, the undeclared love she has for her addressee. The other woman, meanwhile, seems to be all of the following: 1) straight; 2) totally unaware of her friend’s feelings; 3) happily living in Italy, to the extent that the term “blissfully unaware” feels like a safe way to describe her.

I wrote “seems to” just now, and that phrase indicates how Nao is able to work with some of the old postmodern tools without being a show off. We never read the actual letters of The Italy Letters. Instead, the narrator writes about the letters, references what the two say back and forth to each other, as well as what she chooses not to say. What we actually read is a sort of stream of consciousness meta letter. But it’s so easy to get sucked in that I consistently forgot that I was not reading a letter but a mental letter about these letters. Here’s what it looks like in the text:

Later I wrote you, pondering if I should share this news with you, right at the feet of your success, but I felt that if I didn’t share this with you, somehow you would feel slighted … You wrote back, stating that you were engorged with happiness for me. Earlier you said that the rain had gone away.

Do you see what she is doing here? We have the narrator telling us what is in the emails, letters, and occasional phone calls, but we are getting them secondhand. We read that the friend was “engorged with happiness” for our narrator, but our narrator then quickly changes directions, moves us away from these praises to a conversation about the weather. Who doesn’t want to chronicle their successes or praises received from those they love? Why talk about one’s victories, not to mention the praises we receive from a beloved, when we can talk about the weather? Is the narrator hiding emotions from herself, her beloved, or us? This is what I am talking about: Nao’s narrator is illusive, the text slippery, yet it is not just some surface-level thing drawing attention to itself and its cleverness. It is subtle and beautiful in its own quiet way, working to tell one woman’s story.

The way we read the so-called letters, one-step removed, is actually, I’d argue, an important motif in Nao’s novel. Everything and everyone seems disconnected. The narrator’s mother, for instance, is a step removed from her Catholic faith. She, the mother, is suicidal due to a debilitating illness, yet at one point wants to go to paschal mass. Because the church is full, the two stand throughout the service, the mother alternately sitting, squatting, and standing because of her physical discomfort, a sort of religious service built around the needs of the body rather than the spirit, while the daughter is there for her mother rather than religious need. The two are at the service, in other words, but neither is experiencing it in the sense we’d expect. They are immersed in its physical rather than spiritual elements.

Meanwhile the narrator is physically distanced from her beloved, though her desire is intensely physical. Her mental letters describe her insatiable desire for her addressee, her body’s physical need for her beloved, even as their emails tend to veer toward the mundane—cooking, books, work, weather, gardens. Is she so different from her mother, then? Here they are with their physical needs, longing for something that is neither physically present, nor emotionally available in the ways they wish, yet they continue to hold out some hope that their redeemers will come for them. It’s not coincidental that, at one point, the mother asks her daughter why she prays to her laptop.

Higher education and the writing world are exposed here, too, shown to be slightly different than they appear on the outside. The narrator nearly lands an academic position but loses it to a white, male applicant, which is not so different from her experience at an academic conference where her lack of finances leave her in bug-ridden hotel rooms and unable to attend certain events that cost more money. In both scenarios we are shown the ways in which what is said is different from what is enacted, the removal between word and deed. Though the protagonist merely shares her experience, we are left to understand how such worlds, despite our best efforts, can sometimes be more interested in virtue signaling than actual justice or morality.

See, then, how Nao’s book is doing all the clever things we expect from the old modern and postmodern masters. She is allusive and elusive, playing with motifs and symbols and narrations of consciousness and metacommentary and injustice and daring us to link narrator and author, telling a story while so much of the tale rests just underneath the text itself. But the difference, as noted earlier, is that Vi Khi Nao does not seem interested in merely looking clever. There is a good story, right on the surface, and plenty more where that came from in a book that does not try to club us over the head with its brilliance but is willing to reward and challenge anyone willing to see the artistry.

Early in the book, the narrator, asked about being wild and free, recalls her reply: “I told you I believed in constraint.” The fun thing here is that our author seems to actually believe in both, wildness and constraint, as they permeate the book in their own ways, making it a heartbreaking joy to read. Consider this my love letter to an excellent book and great addition to the canon of epistolary literature.

The Italy Letters, by Vi Khi Nao. New York, New York: Melville House Publishing, August 2024. 192 pages. $18.99, paper.

Matt Martinson teaches honors courses at Central Washington University, and occasionally reviews books for Heavy Feather. Recent fiction and nonfiction appear in Lake Effect, 1 Hand Clapping, and Coffin Bell; his piece, “Trout and Trout Remain,” received a Notable mention in Best American Essays 2024.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.