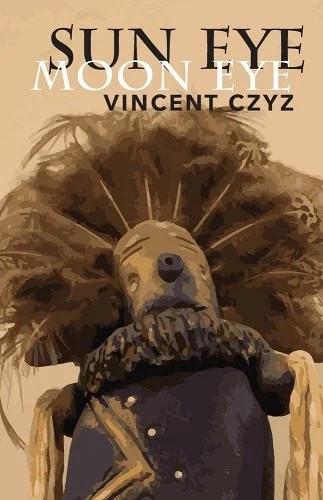

At first glance, Vincent Czyz’s Sun Eye Moon Eye might seem like another daunting 500+ page novel. Nonetheless, we would do well to not only not pass judgment on this because of its cover (which is actually quite gorgeous and thought-provoking), but we should not turn away because we fear a lengthy read. Sun Eye Moon Eye is a violent, magical ride that transports us to the human psyche’s farthest corners and warps reality and the dreamworld so that the two are inseparable.

Sun Eye Moon Eye is the story of Logan Blackfeather, a young man of Hopi descent whose bad choices and lack of direction send him spiraling headlong into life’s wide-open maw. After he kills a trucker in an intense knife fight, Logan finds himself hospitalized in a New York psychiatric hospital, and upon his release, he enters the intermingled world of punks and yuppies. Logan’s release also finds him returning to an entity he long ago abandoned—music—and as new paths unfold for Logan, his past emerges and haunts him, and he finds himself torn between the traditions which help define him and the modern world’s demands.

What makes Czyz’s novel successful is just how adeptly the novel portrays Logan’s struggle to maintain his Native identity yet conform to America’s expectations. Logan experiences racism in a variety of ways. In fact, it is ultimately the trucker’s racism that leads to his demise at the novel’s outset. The placement of this scene is imperative to the novel’s theme and structure as well as the portrayal of Logan’s experiences that shape Logan as a person. Adding a bit of tongue-in-cheek is the author’s incorporation of names like “The Burning Aztec” to represent the bar where Logan’s life takes a turn for the psychiatric ward: “The Burning Aztec joined Chaco Canyon as a memento of a world that no longer existed.” Other imagery associated with both the bar and Indigenous culture, like an Aztec face “painted on an outside wall, the centerpiece of a defunct calendar,” defy humanmade destruction. The face is described as having a “blade of a tongue” which “stuck out” and mocked “the whole business of time and its monotonous cycles, not even bitter anymore about what had happened to Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital.” The modern world of capitalism and the historical reign of ancient cultures clash in the novel’s incorporation of such imagery, and they represent Logan’s internal and personal conflict on a universal scale rather than an individual one.

Nature is a character entirely its own in Sun Eye Moon Eye, and the reliance on natural imagery throughout the novel is important to Logan’s Native identity. Sentences like “Obscuring the sky with mountainous black clouds, the storm loomed” poetically and musically personify the storm. Hyphenated words like “night-charred” beautifully describe the landscapes through which Logan drives. Then, nature becomes an entity associated with the katsina—the brightly colored wooden dolls and supernatural beings who are believed to visit the Hopi people and have the power to deliver rain and exercise power over weather. At times, the narrator’s dependence on passive voice creates a powerful poesy: “The earth through his sneakers was pebbled, the scrape of brush and burned grass muted by pliable soles.” The passive voice creates a metaphysical tone that establishes the dreamlike sensation prevalent throughout the novel.

Furthermore, Sun Eye Moon Eye examines 1980s America—a time of extreme social and economic change. Logan happens to find himself in the heart of New York City during a time in which the city possessed a thriving music and arts scene. However, the progress and promise New York offers Logan juxtaposes his Native identity. By the novel’s end, Logan shares beautiful moments of self-awareness: “Direction was inside him, all around him. Knowing that he’d fallen in with his destiny as surely as his destiny existed, he ran.” Logan’s running represents a return to his ancestry: “While the storm katsina shook the sky, his feet fell like rain, heightened the Earth’s everlasting hum.” These points of self-awareness are also ones of self-determination, and Logan becomes a representation of Indigenous culture’s fortitude in the face of an America in which racism and oppression continue.

Sun Eye Moon Eye dares to tread where very few books do as it treads across the taboo territory of generational trauma in Indigenous peoples that emerges because of the oppressive system into which white governments have forced them. Logan’s abusive uncle/stepfather is the foremost representation of the disastrous psychological toll the historical oppression has taken on marginalized populations. Nonetheless, Logan becomes the force during a number of instances—but especially during the scenes in which he recognizes that he does not have to follow in his uncle/stepfather’s path—that breaks the traumatic, violent cycle.

While it is not a traditional horror novel, Sun Eye Moon Eye resonates with Indigenous dark fiction collections like Never Whistle at Night because, inherently, it is a psychological thriller whose emotional twists and supernatural turns create a mind-bending experience. Of course, what makes the novel profoundly beautiful is Logan’s self-affirmation about his identity and his return to the culture and the traditions which remind him that he “must not stop dancing.” Thus, despite the book’s darker—even haunting— elements, Sun Eye Moon Eye is a novel about hope and a testament to the self-empowerment that occurs when one is brave enough to reclaim who they truly are from a society hellbent on destroying them.

Sun Eye Moon Eye, by Vincent Czyz. Brooklyn, New York: Spuyten Duyvil, March 2024. 588 pages. $25.00, paper.

Nicole Yurcaba (Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. A poet and essayist, her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, and Ukraine’s Euromaidan Press. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University, and is the Humanities Coordinator at Blue Ridge Community and Technical College. She also serves as a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and Southern Review of Books.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.