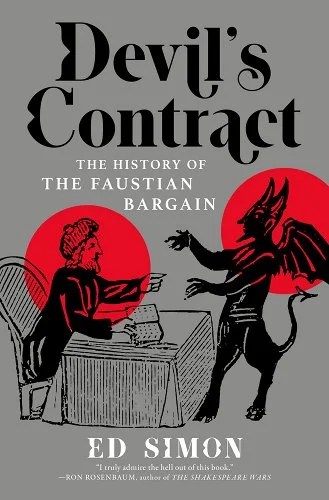

The Faustian bargain, whether in the arts or reality, is alive and well in the twenty-first century. Even in our secular age, we, too, sell our souls for trivial things—e.g., buying an unneeded phone while trying not to think of the slave labor and economic destruction wrought in the collection of its components—or to evil men who make big promises but will require a major reckoning in the future—e.g., a certain orange villain running for the US presidency, to say nothing of our many would-be tech messiahs. So now, here in our strange new god(s)-free age, is an ideal time for Ed Simon’s new book, Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain.

There are, unfortunately, few serious, thoughtful, non-wide-eyed texts on Satan, Mephistopheles, and the like. After you read Elaine Pagels’ The Origin of Satan, Jeffrey Burton Russell’s scholarly-yet-readable texts on Lucifer, De La Torre and Hernández’s The Quest for the Historical Satan, and perhaps Paul Carus’ fascinating-yet-outdated The History of the Devil and the Idea of Evil, you start running short of reading material. And it makes sense: Satan’s place and power in the monotheistic pantheon is too inconsistent in Judaism and Christianity, while his origins are a bit convoluted in Islam, and none are really able to reconcile his existence in a way that allows an all-powerful, all-good God’s judgment not to seem a bit questionable. Thus, there’s a lot of silence from theologians, matched by the secular world’s silence stemming from, well, not really taking Satan seriously.

What Ed Simon does in Devil’s Contract, though, is remind us why we really, really do need to take the Faustian myth seriously. He begins with Simon Magus, who, in the New Testament book of Acts, infamously converts to Christianity for magical abilities rather than a deep desire to follow Jesus. What I enjoyed about this and the following chapter, which focuses on Satan’s temptation of Jesus, is that both are not Faustian tales—they lack many of the key motifs of such a story, including the signing of a contract, soul-selling, demons, witches, twist (or near-twist) endings—but instead are fantastic locales for tracing the origin of the myth. Simon references the Nag Hammadi scriptures here, where Simon Magus is presented in a more heroic light as the so-called gnostic scriptures ask about the actual goodness of the god of Judaism and Christianity, whom they often refer to as Yaldabaoth, a false deity pretending to be the One, the true God. Much like the strange beginning of Job, where Satan is able to sit before the Lord and basically goad him into killing a man’s family on a wager, these scriptures and the stories surrounding Simon Magus make the God-Devil dynamic a bit less black-and-white, an excellent starting point for a book such as this. After all, why is Simon Magus able to use magic after pseudo-converting to Christianity? Why, as the Gnostics ask, do people worship a God is who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful but lets such terrible things happen, not to mention let Satan run loose? Simon introduces counter-narratives and opposing ideas early, producing enough cognitive dissonance to help readers trace the wild evolution of the Faustian myth.

When I say wild evolution, what I am particularly thinking about is this: to talk about the story of Satan—or Faust, or Mephistopheles—a person has to talk about cultural history, too. In other words, a thorough appreciation on the subject requires, along the way, discussions of the arts, history, the sciences, and more besides. Here, again, Simon does not disappoint. Quite the opposite! He touches on a variety of well-known works and events (Paradise Lost, Carl Schmitt’s Nazi philosophy, Faust and Doctor Faustus, Oppenheimer’s distaste for his own nuclear creation, etc), but I admit to learning much from him along the way. I was not aware of paintings such as Lodewijk Toeput’s Landscape with Scenes from the Life of Christ or Ivan Kramskoi’s Christ in the Desert; I’d somehow never heard or heard of Tartini’s maybe-Satanically-composed Violin Sonata in G minor; and, not being much of a cinephile, Simon introduced me to a large list of Faustian films. Together, these passages show that to understand the apocalyptic story of a battle between good and evil is to gain a better understanding of our history; as Simon would tell you, it does not matter if you believe in it or not, these stories are deeply written within us and our culture, so it’s best to be aware.

In fact, as Devil’s Contract progresses, Simon begins referring to our time as the Faustian Age, writing at one point:

Faust is our operative myth because it expresses the madness of a culture collectively endeavoring to bring about the apocalypse all for the piddling convenience that a fossil fuel economy provides. Through his infernal contract, Faust is given certain abilities—he can transport himself anywhere in the world instantly, he has access to all knowledge, he can spy on people unseen—but of course the cost is his soul. What use would he have of Mephistopheles in our century, when Faust could affectively have the same abilities imparted through his smart phone, social media, and the twenty-four hour convenience of Amazon shipping?

In other words, we live in a Faustian age because we are now able to acquire all the conveniences Faust desired, and it most definitely takes a large toll, which looms in the future. Like Faust’s bargain, our bargain, too, is a danger to our own selves as well as those around us and possibly all of creation. It’s a rollicking education. I found myself particularly intrigued by Simon’s chapters on witches and Calvinism in America, respectively, both chapters showing how, from its origins, the US has been willing to sell its soul for the right price, not to mention solely for the sense of being right in general. Beyond providing a smart crash course on both subjects—he is very well versed on the history of witches, accusations of witchcraft, and books about witches from past generation, to say nothing of his knowledge of American Calvinism and its stern, unbending belief in human depravity and election-over-good-works—Simon ties both to something deeper in the American psyche. Witch trials may be done, but false accusations and a willingness to believe whatever best suits us and our belief systems is not. We are often, he reminds readers, as unbending, fatalistic, and harsh as the Calvinist men who once warned that if God has not already chosen you, you are screwed, but also, you are sinners in the hands of an angry God, who is dangling you over the flames of hell. The outward language and actions may have changed, he writes, but such ways of thinking lurk deep in the American psyche.

A downside to what is overall a fantastic book is the moralizing. Do not get me wrong, I agree with the Simon about the problems we have created for ourselves—everything from racism and nuclear weaponry to idiotically short-sighted environmental pillaging and playing with totalitarianism. But I’d argue that almost anyone who reads this book already knows this to be true. Beyond that, though, is the problem with calling such things Faustian. Yes, you can do so—hell, I made such a reference at the start of this review—but there’s a bit of a slippery slope here. After all, if my buying a massive new pickup truck is Faustian, then perhaps, too, going to work is as well. The former implicates me in environmental destruction, but the latter is me giving up time in my one and only life solely for the sake of money. The other issue I ran into in Devil’s Contract is Simon linking the creative process to the Faustian bargain. He points to certain artists, particularly the Surrealists, who quite intentionally got in touch with the darker parts of their minds, but also sought out darker metaphysical realities in search of creative, artistic truths. Soon enough, the implication seemed to be that good art comes from a Faustian bargain. And though Simon does not make such an implication in a fire-and-brimstone manner, I still disagree. To talk about the Muse or any other metaphysical inspiration for art is to denigrate the years an artist put into learning their craft, the hours they put into a particular piece. Even something like Rilke finishing two poetic masterpieces—the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus—in February of 1922, belies the years he put into honing his skill as a writer, to say nothing of how the poems had been percolating in his mind. Indeed, the Faustian bargain I see with artists is not selling their souls for creative ideas, but doing so in the manner of spending so much time creating at the detriment of other parts of their lives.

Devil’s Contract is its best when it is giving us more historical information to help contextualize the wildly interesting Christopher Marlowe who produced Doctor Faustus, when Goethe wrote Faust and also met Bonaparte, when Bulgakov had to secretly distribute The Master and Margarita, or when Robert Johnson supposedly walked down to the crossroads to sell his soul for the ability to master the blues. More of this would have been excellent—works like Gertrude Stein’s Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, Washington Irving’s “The Devil and Tom Walker,” to say nothing of The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” or half the songs of AC/DC don’t make an appearance in the text. Moreover, it would have been fantastic to see Simon delve deeper into the ways the Faust story has been appropriated and reimagined by those seeking liberation from oppression, works like Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun or Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Devil on the Cross, or the stories “The Greenest Eyes” and “The Narrow Way” in Liliana Colzani’s recently released You Glow in the Dark, to name just a few.

In Simon’s defense, though, his book is less about cataloging the many Faustian tales out there and is, instead, ultimately meant to convey the dangers of selling our souls for power, comfort, pleasure, or even knowledge, and he does do just that. And if I happened to enjoy the book for different reasons than what he intended, that does not take away the fact that it is a reminder of our moral obligations in the Anthropocene/Faustpocene, nor does it take away from the fact that it is the boisterous education in religion and the humanities that you possibly did not know you were looking for or needed. For myself, I teach a course on Satan, and I think I will be assigning Devil’s Contract, as it is, for the most part, the book I wish I’d written, and in Simon, I’ve found a fellow traveler.

Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, by Ed Simon. New York, New York: Melville House, July 2024. 336 pages. $28.99, hardcover.

Matt Martinson lives and teaches in central Washington. You can find his most recent fiction and nonfiction in the journals Lake Effect, Coffin Bell, and 1 Hand Clapping.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.