My first experience with Meg Pokrass begins with First Law of Holes, a compilation of fourteen-years of flash fiction spanning six collections, plus some beautiful new work. There is a lot to unpack in Pokrass’ stories as she explores illness and care, marriage, divorce, dead spouses, childhood and nostalgia. Reading such a large collection of flash at once has also keyed me in on an integral caveat to the form: the more my eyes graze the words, the more the scarcity of information makes itself apparent, the more inherently surreal the form becomes.

First Law of Holes begins with a woman who has started an affair with a man much older than her. Their age gap is a point of contention to the narrator, and she explains that this contention is rooted in her trouble with younger men:

My young husband disappeared after going for a long, mindful ultra-run. “I like the look of that path,” he said, and I never saw him again. I knew there were mountain lions around, but they never found his bones. Thankfully I heard from him a few years later. He wrote me a postcard from Jakarta to say that his knees, hips and spine had finally given out.

That’s what unhappiness does to you,” he wrote.

By the time I turned 27, I was tired of the young ones, their perfect bodies and deeply unsatisfied souls.

There is a weightlessness to the piece which may read as absurd or fantastic; the narrator, in the end, lifts the ninety-year-old partner off the couch and dances with him, and I can’t help but picture him as a doll. What I see in the end is a woman who is not only worn down by her dissatisfaction with people her own age, but by her inability to take care of them.

Pokrass’ longer pieces are often divided into multiple sections, and I figured out early on that her work loves to skip around in time, from adulthood to childhood, from dream to reality. A discovery I made here is that each section, too, can be read on its own terms; they may feel like parables. In “It’s Good to Have You Back,” for example, there is some overlap between all the men the narrator had loved—they’re swollen, broken down, in need:

“When I was sixteen, the year he went to prison, my lips were red and my cheeks sweet-smelling. I danced in the living room, dreaming about the kind of bad boys I wanted to love.

“I’m going out,” I told my mother, who distrusted most men. She told me Daddy had killed her roses before they took him away; rode over them with his motorbike. “Your father was careless,” she used to say.

The fragmented nature of these stories lend to the fabulist tone of the overall work but never strays too far from the real.

A lot of Pokrass’ writing shows an interest in the way young people treat one another, and how the attitudes of younger people colors nostalgia. It is important to note that Pokrass excels in its depiction of youths. Teens grow realistically into their bodies, siblings fight, we discover sex and longing. One of my favorite stories in the collection was “You Should Know This,” which showcases the interaction between two young siblings:

Around eight o’clock, his bedtime, I told him he was adopted. He was six now and should know this, I said.

He grinned, doing the crazy tap dancing routine mom taught him. Shuffling off to Buffalo.

“Mom said you had to be nice to me,” he said.

“Well. Finny, that’s what I’m doing.”

He loved dancing, as though he had batteries—could do it all day, all night. His feet were on all the time.

“You lie,” he said. “You just don’t want to be my sister.” Finn could be a very unattractive child.

There is a real sense of care in the sentences that becomes visible when two characters are speaking to one another. It’s interesting that throughout the collection, when Pokrass’ stories rely on dialogue to see them through, they also feel surreal in that lines seem to be missing or displaced, emphasizing a sense of being and identity over input and reaction. It all feels honest and implicit, especially for flash fiction, which tends to show so little.

I recommended Pokrass’ work recently during a conversation about putting together prose collections. The question of how to develop and structure a collection is an interesting one (I recommend David Jauss’ essay on building a unified collection in Alone with All That Could Happen), and I imagine the work of building a unified anthology covering over a decade of work feels like a feat of literary engineering. Not only does Pokrass pick out work that fits together, but I can see identity in her pages; these don’t feel like fictional pieces so much as they feel like glimpses into Pokrass’ own experience. This is of course speculation, but I feel that it’s important to point out; as a result of the realness of these vignettes, it becomes easy to push against the ingrained obligation to identify theme or pattern. I wonder how the reading experience might have shifted, for instance, had the six collected works been mixed together. I find myself imagining the writer/speaker through the years of the works’ composition, one way or another, and it’s fascinating to see.

While I want to push against the need to find themes or patterns, I can’t help but think about the aboutness of the collection and the choices that have been made in its construction. What’s important is that First Law of Holes is best read slowly. The tendency to read quickly needs to be stifled—even when these selections do not quite fall into the category of prose poetry, they each may feel tonally different than one another, touch on different themes from one story to the next (despite my attempts to read in a less academic sense), and I became aware as I read through the collection that tone and feeling had the tendency to bleed through from one piece into another, seemingly unrelated one. Perhaps this is intentional—for example, in “Teeth,” the protagonist examines her spouse’s childhood teeth, which have been preserved by his mother in a box. She imagines him young, trying not to lose his teeth. The story feels odd, though with sweet undertones:

Thinking about [his mother keeping his teeth] created a briny feeling in her mouth. She imagined him a little boy so often these days. Laughing too carefully, throwing the world off.

How he would have looked back then, trying not to lose his teeth.

The very next story, “Dowager’s Hump,” is about perception in relationships, and maybe expectations: a husband discovers that his wife has started showing a hump on her back, a genetic malady she has kept secret until now:

“Maybe you would not have married me if I’d told you about the family problem?” I said, once, very softly.

My husband would twist his torso away from me, right there, in his chair.

My hump, like the moon, would rise a bit higher.

Sometimes, doing dishes, my mother’s hump, my grandmother’s hump, would feel very close. I’d find myself in the lobby of some new-age healer’s office, trying to explain.

I’m not saying there needs to be a connection between the two stories (someone else may see an obvious connection), but it points to a need for slower reading, to look carefully, to reassess how one approaches literature in general; the need to explain oneself and come to terms with identity could intertwine with the need to understand what others have gone through, are going through.

These are some of the funniest stories I’ve read in a long time (“Geode”); these are also some of the saddest stories I’ve ever read (“You and Your Middle-Aged Cat); although some of these characters feel similar—I would be willing to bet a lot of these pieces are based on the writer’s experience—the stories each feel intensely individual, evoking experiences both nuanced and familiar.

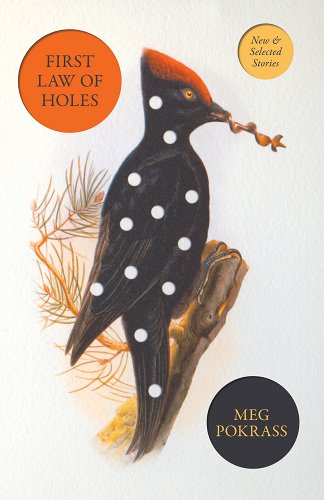

First Law of Holes, by Meg Pokrass. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Dzanc Books, September 2024. $16.95, paper.

Garrett Ashley is the author of Periphylla, and Other Deep Ocean Attractions (Press 53, May 2024). His work has appeared in The Normal School, Asimov’s, Sonora Review, and DIAGRAM, among others. He lives in Alabama and teaches fiction at Tuskegee University, where he edits the Tuskegee Review.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.