Darrin Doyle’s Let Gravity Seize the Dead invites us into a new kind of psychological horror, one that relies on brevity and compression to create the subtle scare tactics that keep us engrossed. Within the novel’s 141 pages, we uncover a trauma-laden story that examines the past, the present, and the myriad of ways one cannot escape the decisions of their ancestors. Set in 2007, the book follows Beck Randall, who moves with his wife and two teenage daughters into an abandoned cabin his grandparents built a century ago. Beck’s daughters, Tina and Lucy, slowly discover their father’s family’s violent history—a discovery that leads them to the Whistler, an eerie figure permeating the entire area surrounding the cabin, as well as their family’s story.

Let Gravity Seize the Dead tends to avoid many of the tropes inherent in Appalachian/rural-themed horror. Granted, it does rely on one major stereotype which, since the 1880s—particularly in states like West Virginia—has continued to this day: incest. The girls learn that their great-grandmother’s brother raped her, resulting in the birth of their grandfather. However, the incorporation of this stereotype is not the novel’s major focus. Rather, it leads to a more explicit warning—that attempting to return to the past might yield unsavory discoveries which can drastically shift a family’s or an individual’s course in life. It is through Beck’s character that this warning becomes the most evident. Throughout the book, we see that Beck cannot really explain his motivations for returning to a place long-abandoned by his family. He ignores his father’s arguments that the place is basically cursed; instead, in a state of blurry possession, he pleads with his father to sign over the family land—which Beck’s father does reluctantly. We almost expect a Transcendental, return-to-nature-return-to-self story when Beck returns to his family’s land. Instead, what we receive is a heedful vetting of just how cyclical human behavior actual is—and what power, self-will, and determination an individual must gain and possess in order to break that cycle.

While dissecting the ancestral and personal cycles which ultimately shape an individual, Doyle’s novel also deconstructs toxic masculinity. Again, this dissection occurs primarily through Beck’s self-awareness. He frequently reflects about his sexual past as a teenager and college student and his pursuit of women. He asserts, “Men were pigs, plain and simple.” Astonishingly enough, Beck does not exempt himself from this observation, acknowledging that a man “would destroy family, career, self-respect” and would abandon “reason, decency, control,” when one dangled “a girl in front of him.” Simultaneously, he also remembers how his father, despite his marriage to Beck’s mother, kept mistresses and possessed a wandering eye. Beck’s reliance on alcohol is another key element in the novel’s scrutinization of toxic masculinity, and one of the most alarming scenes is when, in a local bar, Beck drinks too much, grows mouthy towards some of the locals, and leaves angrily. Throughout the book, however, we witness Beck’s post-work reliance on alcohol as a coping mechanism and a suppressant of his urges.

Despite its gritty, dirty inspection of human behavior, one cannot read Let Gravity Seize the Dead without noticing its beautiful, poetic, and almost spiritual observations about nature. Beck’s daughter Tina tends to make the most intimate observations of the nature surrounding the cabin. She states, “The woods are like a person,” describing the woods’ moods as “calm and happy” and “hot and mean.” Her observations about nature not only remind us about the interconnectedness humans share with nature, but also about the interconnectedness between an individual and their ancestry. Tina observes, “When I see a blackbird of squirrel or deer I think they’re relatives of the same animals you saw. Their blood is their blood, like yours is mine. You’re inside me and my sister and my dad.” At other points, the forest becomes an all-consuming, almost evil entity, which fights against the settlers’ efforts to tame it and garnishes “forces to drive them away.” The book’s reliance on natural imagery is also important to understanding the concepts of ancestry, individualism, and family, and one character in the book describes people as “the same as trees” and that if one person wants to know another, they should “check underground” and “under the soil” because that’s “where the story is.”

The significance of learning and understanding one’s story, too, is an important theme in Doyle’s book. After all, how can one break cycles of trauma and violence if one does not understand the cause—and ultimately the effects—of such behavior? Nevertheless, the book also holds a much-needed message about letting each person discover and create their own story. This is most exemplified in Beck’s relationship with his daughter, Lucy. After the move to the cabin, Lucy is undeniably miserable. She misses her friends and her school, and she finds homeschooling tedious and sheltering. After she develops an online relationship with a local boy named Noah, she realizes she must keep the relationship secret from her father, because she fears his reaction. Beck’s strict enforcement of rules and expectations leads Lucy to begin sneaking out with Noah, until one day, after learning about Lucy’s relationship with Noah, Beck acquiesces and says the boy can visit. Beck and Lucy’s stressed interactions, and particularly Beck’s dominance over his daughter, exhibit how one individual’s disruptions of another person’s freewill and self-determination create an aberration in that person’s story. It is these less overt philosophical interrogations that add to the book’s suspense and psychological tension.

At first, Let the Gravity Seize the Dead might seem to bear a message about how one should avoid living in rural environments where outsiders may not be welcome and unforgiving landscapes possess their own agendas. While some of these themes do appear in Doyle’s book, the novel owns a much more significant narrative that is relevant in contemporary discussions regarding taking ownership of one’s actions and agency. Rather than ostentatious, gut-churning gore, it relies on poetic writing to create a psychological, even spiritual and existential, minefield. The past mysteriously and hauntingly blends with the present so that the events, much like bloodlines, DNA, and family lore, become inseparable. With the publication of Let Gravity Seize the Dead, both Regal House Publishing and Darrin Doyle dare to reinvent the rural gothic subgenre existing in the horror world today.

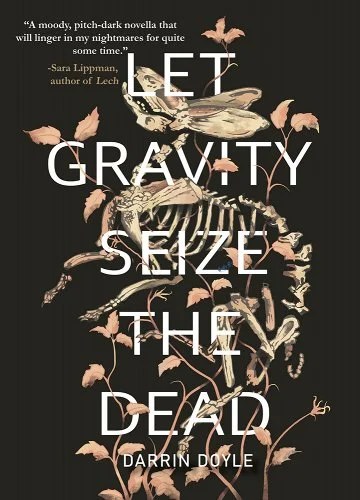

Let Gravity Seize the Dead, by Darrin Doyle. Raleigh, North Carolina: Regal House Publishing, July 2024. 141 pages. $17.95, paper.

Nicole Yurcaba (Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. A poet and essayist, her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, and Ukraine’s Euromaidan Press. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University, and is the Humanities Coordinator at Blue Ridge Community and Technical College. She also serves as a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and Southern Review of Books.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.