And there was Michelangelo, the famous Renaissance painter who I worshipped as a child, writing his name over and over on the pages of my notebook, as if the meaning of life was there in the syllables:

Michelangelo

Michelangelo

Michelangelo

Mich-el-ang-el-o

I grew up on a farm, and the only books I had access to were bibles, romance novels, and a set of encyclopedias that I read for fun. When I reached the M’s, I was captivated by this great artist who lived so long ago, who depicted angels with complexity and ferocity. I checked out a book about him from the school library, marveling at the perfection of each sculpted body, the glow emanating from the smooth marble. They looked like they had been working in the fields, biceps shining like the naked arms of farm boys as they were mucking stalls, or when the harvest was interrupted by a strong rain, and they took off their shirts, their skin lit by an inner fire. The fire of work. The heat of battle. I recognized Michelangelo’s angels. I saw them every day, and not just in my visions—although they were certainly there. The people I grew up with, during the brief flush of youth, before life crushed them, were angelic, fierce, noble. Their hard work, all that digging into the land, brought them into contact with something ethereal.

In the Kingdom Hall, no beauty was allowed. As a Jehovah’s Witness, I was expected to focus on my inner experience of the divine. There were no stained-glass windows, no murals, no crosses or altar pieces. The walls were painted beige, the room was lit by florescent lights, the banal hymns were sung off-key. There were certainly no sculptures or grand architecture. Michelangelo’s work, for my mother, was evil incarnate. In Italy, he was called Il Divino. But the Divine One is easily transformed into the Evil One, and of course, every demon was once an angel.

As I flipped through the pages of Michelangelo’s work, I experienced the terror that often accompanies beauty. The ferocity of the divine is wild, dangerous, sublime, full of grace, brutal, efficient, the life-giving sun that burns your eyes out if you look straight at it. It’s like catching a tiger by the tail. Yes, I saw his terribilità.Awe-struck, my perception began to shift, the images vibrated with life. I felt a tiny crack, a fissure in my consciousness. A delicate ray of sunlight arched over the plain beige walls.

But isn’t this why the Jehovah’s Witnesses abhorred Catholic artists, especially the ones from the Italian Renaissance? The church elders said that such art would be a corrupting influence, and they were right. Michelangelo’s work is proof that what they called the devil was God, and looking his works, I felt God’s true presence for the first time. After that, I was guided by something within, not the voices from the outside. Scriptures were only words, the speeches of religious leaders only breath. Real art couldn’t coexist with dogma because it resisted binaries, it opened into chaos. The true experience of the divine is something totally beyond our control or understanding. There is no controlling God or God’s chosen manifestations. Michelangelo’s work shows this very clearly—the touch of God lifts each work beyond the realm of the human. It is evidence of the true nature of divinity—the glint in the eyes of a wild animal, a river flooding its banks, hurricane winds snapping trees in half, the sharp edge of a cliff carved by waves, the luxurious scarlet of blood as it leaves the body. But what does any of this have to do with “greatness”? Perhaps originally, it meant the greatness of the divine as it shines through a human artist. Now it means the greatness of a solitary genius, acting alone, special, above others.

And thirty years later, in Florence, the city of the Divine One’s birth, I had a vision. After visiting Michelangelo’s tomb, I sat at the kitchen table in my apartment on via Ghibellina and felt wind all around me. The air thrummed with energy, and that energy entered into my chest like a flock of birds. I felt a sense of chaos through my body and stumbled into the living room where I collapsed onto the floor. As the energy mounted, I began to cry, perhaps to rid my body of some of the excess energy. Scrambling for a notebook, crawling on my hands and knees, I wrote a twenty-page poem. The words were only a placeholder for the energy. The space was there, but the words were simply architecture.

Michelangelo is perhaps the most celebrated artist of all time. He was able to create works that transcend the limitations of the imagination. His sculptures breathe, the blood travels through the veins in the marble. All I could think of during this visitation by who knows what—This can’t be happening. I’m not capable of writing about such greatness. I am an Ordinary One. Worse, I’m a Crazy One. Instead of receiving the energy, this grace, I tried to compete with it, to fight it, to judge it, and that is why I couldn’t understand how to process it. When I surrendered—accepting it as destiny, not arguing or questioning, then it lit me up. Possessed by something Other, my visions began to spin out, billions of winged eyes blinking in unison, a spiral staircase leading up and down simultaneously. I became possessed by something inhuman.

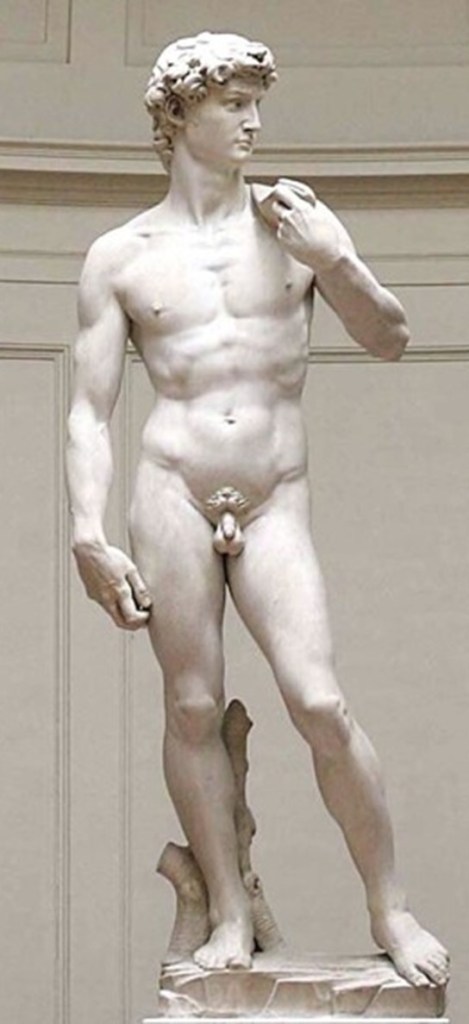

First, I saw the “David” statue. The real statue is seventeen feet tall, but in my mind it was taller than a house. David’s left hand holds a slingshot for shooting giants. His right-hand falls to his side, a slight tension in the fingers. David is an Ordinary One. Goliath is Il Divino. David regards him carefully, relaxing into the moment. He is worried, but his mind is also working. David knows that greatness may be extinguished if his rock hits a precise location on the giant’s head. It does. David wins, but now he has become Il Divino. And now that David is the giant, he has giant problems. His likeness decorates millions of bags, posters, and busses. On a popular postcard, even his genitals wear sunglasses.

Il Divino,

Master of three arts:

painting, sculpture, architecture,

& sometimes poetry.

Divine One,

You hold the Christ Your face looks out, You would have destroyed it allif not The mother throbs Today I will spread my ignorance I’m American,which means Michelangelo, when you whisper into my earI don’t I have a shopping addiction,insomnia, drink There is only nothingness. I feel your presence again,flipping Content to rupture, nightmare of a skull’s Death is like that:hot. But is there something, I can feel your dust. Michelangelo,

my hands are your hands.

Meanwhile, in the sixteenth century, the Divine One writes: I alone keep burning in the shadows I close my eyes, reach through time, and smooth his hair back. Don’t cry, Michelangelo. Later, when I’m crouched under my writing desk, he does the same for me. * When I visited the Dolomites on my trip to Italy last summer, I went into an area that was off-limits to hikers. As I ducked under the ropes surrounding the “Danger: Livestock” signs, I wandered through a valley touched by magic. My husband, Michael, was the first to spot the colorful cows lounging among wildflowers. A rust-colored calf ate grass next to the white and gray fur of an adult. The reasons for the signs dawned on me as I saw two white bulls approach. The bells on their necks chimed majestically in the mountain wind as they dipped their long, gleaming horns. Not a bad way to go, I thought. I grew up as a flat-land girl, and the sight of the mountains always left me with too much feeling in my chest, more than what my physical form could hold. I walked around that way all of the time in the Dolomites, and I wondered how the yearly inhabitants performed any task whatsoever. I let go, melting into the jagged spires of earth. As I did this, I felt the wind pick up, and heard a song drifting through the air. As I noticed the bull’s short bursts of breath, I sang to them: Blue sea hums through his body. Night rivers touch every hour, I touched his fire in the meadow. Darkness untold every hour, Clover, Hover, The bulls lowered their horns. They were young, and not yet so aggressive. They followed us for five miles, even crashing down the steep hill next to a waterfall to watch us sit on the rocks and write our poems. The sound of their bells seemed to come from within my own body. * Michelangelo, I share your longing still whirring for now. The ghosts lean in and I drink to the dying of the earth, sun has passed, every drop of blood turned to dust. Is it my fate to be their nightmare, vast and all night the wind blows through a graveyard meaningless scrawls like the notes of the song, rivers burn through my veins, strangers pass through Michelangelo, Do you feel it?

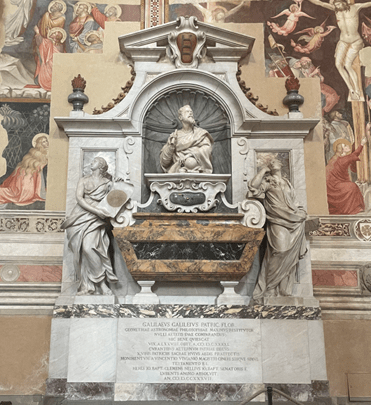

Wind carves trenches onto my face, tangling my hair into impossible knots. In Santa Croce, I breathed in a dust particle from your decaying heart where it will live in my chest for seven years: shadow of darkness, marble ligaments, light on a steel face, eyes that never tire or blink. Your nephew brought your body back to the Church of the Holy Cross. They say your corpse smelled sweet, like a saint’s. I felt you vibrating there, your bones an icon of holy power, like the blood of Christ. I’ve always hated the sight of him, emaciated, suffering, nails through his hands (the instruments of creation). What is a nice boy like you doing in a place like this?

My grandmother used to work at Middlebury Methodist as the secretary of the church. While she was designing Sunday’s program, I gathered offerings from the field, and climbed onto the altar where Christ’s body was hanging. When I stood to my full height, I could reach his feet and calves. I licked clovers and cornflowers and stuck them to his feet. I closed my eyes, dreaming of the meadow where I had just been, and I imagined that I was strong enough to take his body down, to carry him outside, and cover him with blue petals. I would pour water over his hands and feet, bury his crown of thorns, twist the hair back from his face, singing to him of only beautiful things—clouds, feathers, candles, glitter. Let me show you the way. Please, get down from there.

* Michelangelo writes: There’s an art of beauty, which, if everyone My love, you are mistaken.

Now I’m a cherub holding a bowl holding the golden cup pure fire down my throat and through the rivers I’m a mountain gleaming with marble like snow, turned to streetlights. a backlit sepulcher,dying ice that once covered nightmares The body opens The heart is a gate as each cell calls to you space across space, like the bells of San Miniato, Fuck you, Michelangelo. on the hill,how I became that mint Stone and spike, but which you heard You’re a raven I feel your breath on my neck, sickle moon as a different bride and groom What would you sculpt now? Would you lose hope as we have, offering What would you believe in? The same? What if you knew about genocide that your statues would decorate * Sometimes there are eyes around my bed at night. When I get closer to them, I see purple vortexes that shift and change into faces—a man with glasses, a woman walking among trees, a child with wild curls around her head—or sometimes just a tall pine, the hollow eye sockets of a demon, a maple leaf, a fairy with humming wings. And I know these purple eyes to be the eyes of the dead and sometimes you reader, yes you. I receive your presence, and there is a brief moment where I see a fragment of your life, your face, your garden, and I know I’m probably not okay, but I can’t help it. I really believe this to be true. After reading one of my books, a friend messaged me to say that she envisioned herself hugging me when I was a child, and she described a moment in my life where I felt utterly alone. And I remember sitting behind the house and feeling what I thought was an angel gently holding my shoulders, and I felt peace and was able to go on. Michelangelo, was that her? Do you see me now, hundreds of years later, across the world? I am writing to say thank you for your work. It has made me realize that the divine can and do possess us, just as we possess and comfort each other. When I first heard your name, I thought you must be the archangel, Michael. Like my own husband, Michael, who saved my life when I was twenty-six. The first time I saw him, I felt wings in my chest, the storm of the divine, and I knew (but trying not to scare him) that he was the one for me. But back then, in my early teens, Michelangelo, I prayed for you to find me and carry me to a place where I could be free of everyone’s constant, contradictory commands: Wash your hair, Michelangelo, * You write, “I’m fortunate that the fire of which I speak still finds a place within me, to renew me, since I’m already almost numbered among the dead. Or, since by its nature it ascends to heaven to its own element, if I should be transformed into fire, how could it not bear me up with it?” You write, “in hard stone.” Beatrice and Vittoria, Their bodies manifest

as spirit.It shines from them What is this fire, Where is the mystery, Michelangelo, I would have carried your body Blue sea. This fire from which you speak So as artists, what are we left with?

Fire, I shout a radioactive * Another dream of Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgement” reveals the underworld within the heavens, the chthonic labyrinth inside of the ethereal blue. The angelic figures grow golden horns that curl above their heads like crowns. I hear a heartbeat, a drumbeat, deepening into the trance. I begin painting these figures obsessively, although I have no training as a painter. I keep making the shapes as best I can, with clumsy brushstrokes, with my bare hands, fingerpainting like a child. I’m possessed, and because I have no technique to support me, the colors drip in muddy rivulets, pool on the floor in rainbow swirls. I call it “Michelangelo in the House of Hades,” a tribute to the fire he wielded. Exhausted, I lean my head against the wet paint. It’s in my hair, stuck to my toenails and chest. When I look in the mirror, I see bright blue horns arching across my forehead, a blessing, a mark of something holy. * Sound the drums. My chest is a tomb of grace. I feel the cliffs as my own skin. blue like the sea around her, Tectonic plates collide within, a red wave rises from a crack, Something sparks,gorgeous and terrible, The one who risesis not the one who fell, A leaf issculpted by trial and error, Michelangelo, I’m tired of having to prove myself. Because the rock is calling to me, before language, before rain, ancient of blue. The strands of my hair “I can’t help seeming to lack talent and art / to her who takes my life … my lofty lady, calm lady; from which I should learn / that what I can do leaves me unworthy of her.”[iii] The beloved is always beyond talent, beyond skill. The beloved lives in an untouchable center, which can’t be experienced, a dense egg that contains the mass of the universe, feather of my feather, eye of my eye. The stone’s anthem is inscribed on my crooked spine. The scroll unravels, blood-ink, beyond time. There is something about you, Michelangelo, that summons the edges within me, collarbone cracked like a cliff’s edge, perhaps your ability to outlast everyone? Ringing like a church bell, the ocean and sky are indistinguishable deep blue behind the Madonna’s head and the sun burns us all at once. We are the last shadows before dawn, Life is special to the dying, the ordinary Brandi George is the author of Gog (Black Lawrence Press, 2015), Faun (Plays Inverse, 2019), and The Nameless (Kernpunkt Press, 2023). Her work has recently appeared in American Poetry Review, FENCE, and Orion, and she has been awarded residencies at Hambidge Center for the Arts, the Hill House, and the Time & Place Award in France. She teaches writing at FSW in Fort Myers, Florida. Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses. ____________________________ [i] The Poetry of Michelangelo, trans. James M. Saslow., Poem #2 [ii] The Poetry of Michelangelo, trans. James M. Saslow, Poem #97 [iii] The Poetry of Michelangelo, trans. James M. Saslow, Madrigal #149

& Madonna,the Great Mother,

the Goddess,the energy

of creation,both aspects

of masculine & feminine.

frozen in 1555.

The “Pieta” is half-formed.

Christ’s arms shine with divinity.

You smashed

his face with a hammer

when the marble failed

you,a vein in some unsightly place.

The mother’s face and body are blurry,

still one foot

in your imagination

where I catch it,

Michelangelo.

for a friend.

with the blood of her son,

scarlet petals disappear

into dust.

across the city,Michelangelo, which you

have made famous.Millions of people crowd in

to see the things you created, “David,” “Bacchus” (my favorite).

What part of you was captured there?

it is my destiny to annoy Europeans.I’m the shadow

and shepherd,the darkness where their ancestors fled.

understand and it is lost.I’m a lost cause,

selfish and useless.

too much. I might be schizophrenic. I’ve been dissociating again,

blacking out. Just look at this stupid poem.

I’m a poet and it’s a fucking joke,

Michelangelo, and I’m not strong enough to survive.

through your book of poems, I pick the words out

from #3 at random and splice them into mine.

blood toes,vengeance stone-

cutbones,white marble

flesh.They saylyric

poets have cold hearts.

Rhythm underground,

the rhythm of fire,

delicate cheekbones.

Can I call you Mike?

Nothing is holy.

God haunts the edges

of a burning grove,

summoned daily for

shopping bags,like you.

in the air when I’m quiet,

the blue beyond death,

a raindrop slipping

down the marble face,

something inhuman,

dare I say,divine?

Can you feel my shadow?

when the sun strips the earth of its rays;

everyone else from pleasure, and I from pain,

prostrate upon the ground, lament and weep.[i]

Blue flower blooms from his body.

the wilderness of his sleep.

The sun burned gold through the meadow.

the ashes of his sleep.

Lover,

Cornflower.

to become the light, but I’m just a bag

of skin and machines. Wind and water are

I receive them. Here, take this espresso,

Michelangelo. You drink the steam as

drowning in the sea, when we are both dirt

and wind on hard stone, and everything green

Sun rays rip through me, collapsed on the rug,

the burden of my promise extinguished.

sea without memory or fish? When I see

the Alps my heart grows thorns and I can’t sleep

rising as mist around gray monuments.

I run my fingers over tombs, names, letters,

the first note that exploded nothing

into something. The pines scratch my eyes out,

my chest without record,scattering my bones

across the world with no marble monuments.

the angel you are

I’ll never know.

Each stranger’s look summons the god within the stone, tomb for the new ways.

brings it with him from heaven, conquers nature,

even though it imprints itself everywhere.

beneath your bloody wrists, catching

the divine fire,

to my lips,

tipping back my head,

of my veins

until

the stone wailing

back the starlight

The melody echoes

eternally,

embers of a saint, and the sparrow that whispers

of the water trapped there,

the crown of god,

wings rush back and forth,

crowding gloriously

with asteroid limbs.

from the heart

and closes from the hips,Michelangelo.

where blood spreads its river,

overflowing the banks

from another world.

The futures,the pasts,

planet beyond this planet’s expanse,

the whole cosmos ringing

where I write this to you,always you,

hovering with your cliché angel wings.

Your wings are pale green like the mint

that grew wildly behind our trailer

as I become you now.

Summon your gifts. Kill me before I kill you.

summon the facebeneath all faces,

the heart we never see,

as a drumbeat

within the mountain.

on Neptune’s head, the rain

outside my open window.

above the city, lights on the Arno, distant shouts

of celebration. Each night, I feel you

posing for wedding photos

on the balcony in front of the church.

Cheeseburgers? Spaceships?

What would you paint?

nothing to nothing in the great nothingness

which is sometimes called art?

Would you long to hold the Christ and Madonna?

Would you piss on a cross?

weapons of mass destruction, slavery, colonialism,

global capitalism,

T-shirts and tote bags?

Don’t you want to burn it to the ground?[ii]

do the dishes,

put a dress on,

make yourself useful,

cook dinner,

watch the dog,

watch the children,

listen to your father,

read the scriptures,

respect what is holy,

keep your head out of the clouds,

don’t be cynical,

don’t say “fuck,”

don’t wear a tight shirt,

wear a bra,

don’t be a slob,

don’t eat like a pig,

don’t wear men’s T-shirts,

no, that’s too short,

no, that’s too long,

your hair is too long,

you need to lose weight,

pay attention,

you are too quiet,

why don’t you speak?

Don’t interrupt adults,

don’t be disrespectful,

stand up straight,

sit quietly,

improve your posture,

put your shoulders back,

don’t break the dishes,

OMG put a bra on,

don’t hang your head,

use lip gloss,

use mascara,

no woman should ever leave the house without makeup,

you look like a whore,

your skirt is too short,

behave like a young lady,

get in my truck,

hey baby,

get in my truck,

can I buy you a drink?

get in

baby.

Bitch, I said

get in.

Your hair is too long,

never cut your hair.

Michelangelo,

I just like to say your name.

the divine feminineunyielding,

equal in genius,but untutored,

raw, un-sculpted,without medium

or technique.

and spreads,lighting a path

for the male artist to follow,

channeling the fire of inspiration.

Michelangelo?

the sacred room,

the garden of the angels?

to an open meadow, dappled with sunlight.

I would have stitched your wounds, covered you

with blue petals, dug hole in the bare earth—skin to dirt—

tucked you in like a child and planted

an acorn over your chest.

Blue flower.

burns me. I can feel your ruins.

Ruined, but laughing.

water,

stone, and

ink?

manifesto: clover-faced, sky-clad,

primal, many-headed, sea-serpent.

There is a flame in the mountain.

Michelangelo,

Madonna,calls out to me,

down the path & after.

edges emerge,sharp and deadly,

lava under water.

I touch the blue heart of the earthand am incinerated.

what the heat of the sourcemakes new.

prehistoric roseseat flesh and bone.

Fuck everything that lives.

speaking my names, before time,

lava-born Madonna strips the world

shred into feathers. Michelangelo says:

even the gates

love our death.

becomes extraordinary. We are the dying,

I guess.