In Lauren Scharhag’s collection Ain’t These Sorrows Sweet she succeeds in giving voice to “15,000 years” of ancestors, to the elders who forget how to draw clocks but whose names chime in music boxes, to the young nieces now mothers and mothers now childless, to the blood which flows within her and too easily out of her. She chisels her marble so precisely we can see beads of sweat on her abuelo’s face, we can see a girl shivering in the ladies’ locker room hiding from an older boy, a father straining to hear his family at the dinner table, a classmate with a short leg dragging her foot as she walks to the bus, a young man vomiting and starving from renal failure, a cat losing control of her bodily functions. There is much to live through in these poems, much to survive through, and we feel every pang, every triumph, every release. As Scharhag looks at the broken pottery of our bodies and masks she muses, “it’s all right, darlings, I wasn’t good enough either.” Yet there is a redemption in these vignettes and tableaus, the girl with the short leg gets the “Mansion. Dream job. Soul mate,” we melt snow on our sex-heated bodies in the “Silver dawn,” and we get to “fall in love again / every day, anew.”

Through this journey of a book, through all the tongues of her Latino ancestors, Scharhag wields power through consuming each voice and each sorrow, until her “bones and teeth and tissues are beans and corn,” until she rests “in the shadow / of volcanoes and the breath of deserts.” She invokes the memory of her abuela through the faraway perfume of “dahlias / and passion flowers, birds of paradise, pineapple sage, / laelia orchids, frangipani, beds of agave.” She follows her lineage in and out of prison through the ink in each holy tattoo on her uncles’ skin: “a gourd lacquered in cellblock blue, / and what awaits it all, what comes of all stories writ in skin.” She becomes the grandmother the mother the child simultaneously, as she states “we, though many, are one body, / … parent and child, / living and dead, host and contestant.” She makes herself a vessel to hold all of these years and tales and woes and marks herself “with the language of the deep,” trying not to diminish with age by holding all of her great family inside of her, to not become “smaller and smaller towards the end.” Because as she realizes “When they teach us we should always make ourselves smaller, / this is not what they meant.”

Any many ways this book is a survival monologue, a sorcerers spellbook, a woman’s clear song above the indignities of men. She enters into a room of men who “Talk about women, but only piecemeal. / What women have done to them. / What women do for them. / What women ought to do for them. / What women ought to do.” Her vital voice fills the room: “I say, this is what a woman’s life is. / I say, these are her experiences. / I say, these are her thoughts. / I do not raise my voice. / I make no demands.” She tells of men assaulting her with photos of nakedness and how to navigate the dragons on these supposedly safe streets. She finds solace in her own self, without armor, as she states: “i shimmied out of my / suit for just a few minutes because i / wanted to know what it felt like to let / the night caress all of me.” For the women inside her and in her life she regains all their power, “You step outside / the world. You invite the exotic into your kitchen. / You eat cake and eggs and summon serenity / with a brushstroke.”

And throughout this powerful and gritty collection, there is the most delicate music seasoned with fire: “braised with beef tendon, / corn and chilies, / tortillas, / each bite taking me / back in time / through Cordoba and its / bloody bull rings, / through Moors and mosques, / all the way to Rome.” Or in the poem “Dusk”:

When the lilacs end,

fireflies constellate

in the dying fragrance,

lighting the white viburnum.

On the patio,

my mother drinks

sticky-sweet wine.

Black gnats, undaunted

by cigarette smoke,

circle the rim.

Her masterful lyricism flows even at her most effusive, as in the fifth stanza of her Cadralore: “I’ll never stop seeking this nowhere place, part dream, / part memory, all Zhuangzian dilemma. There, we will talk of alphas and omegas, plant zinnias / and milkweed, and become ghosts simply because there’s nowhere else we’d rather be.” This collection is a prayer and a revelation and an elegy and a map and a manifesto and a treasure. Let it wrap you in its awakening and in its sleep.

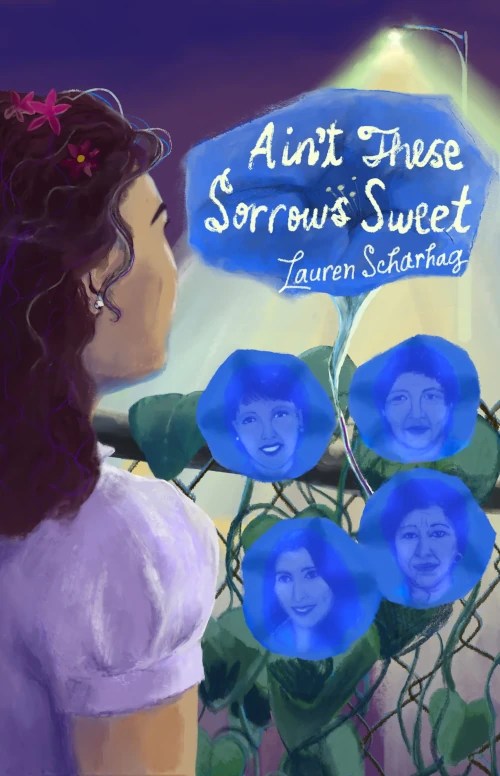

Ain’t These Sorrows Sweet, by Lauren Scharhag. Roadside Press, June 2024. $15.00, paper.

Scott Ferry helps our Veterans heal as a RN in the Seattle area. His tenth book of poetry, Sapphires on the Graves, is now available from Glass Lyre Press. More can be found at ferrypoetry.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.