Remember learning about the so-called death of the author, that brief moment where, in the world of literature, authorial biography—to say nothing of intent—did not matter in the least? If I’m being honest, I sometimes find myself missing the playfulness of the postmodern old guard, which feels as if it has been entirely replaced with a twenty-first century staid sincerity and safety. Please don’t get me wrong, it’s definitely not all bad! But if I’m being honest, I find myself a bit bored these days.

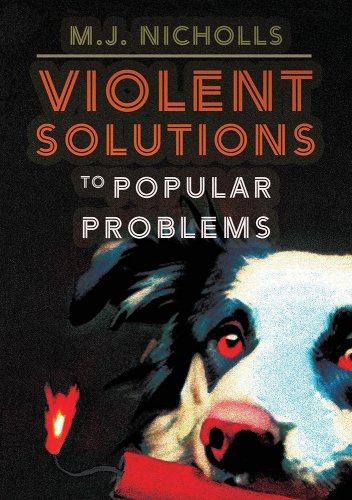

Fortunately, the proverbial baby need not be tossed away with its equally proverbial bathwater, as demonstrated in M.J. Nicholls’ recent story collection, Violent Solutions to Popular Problems. Here we see metafiction, puns, heaps of irony, self-effacement, mockery, and oh-so much wordplay, all while managing to say something about the times in which we live. In one story, for instance, rather than blatantly projecting memoir-as-fiction in an attempt at authenticity or social critique, Nicholls features none other than M.J. Nicholls, who “sat, watching a paid actor read his own prose back to him, entirely for his own amusement.” I’m reminded, reading such passages, that I became a reader because reading can be fun! Yes, it can speak to our social ills and existential fears, and Nicholls does just that, but he also, if we let him, reminds us that Literature and fun are not antitheses.

In other words, a puke-smeared, toothless Don Quixote can stop rolling in his grave.

It seems Nicholls is not only interested in eschewing some of the current norms of the literary establishment but skewering—or at least playfully prodding—them in the process. Take the collection’s first story, “Librarian of the Year,” where we meet the aspiring novelist Clara Draywort, who “calculated that by cultivating an unusual history for herself, her chances of market success were seriously bumped.” That checks out. But she meets her match in the newly minted “librarian of the year,” Isobel, the story’s protagonist, who has “learned that writers … were irritating and unlikeable 87% of the time,” barely read themselves, and need to be reminded that the writing, not self-promotion, is the most important thing. Or, as she says: “It’s imperative, in an age when Twilight fan fiction plagues the bestseller shelves, that we recognize the atrociously untalented and stop them from polluting our libraries with their dire outpourings.” Link that statement with a nearby description of a whining Adam Thirlwell moaning about readers misunderstanding “his extremely annoying blabber of a last novel,” and you’ll quickly catch on that Nicholls is both hilarious and blunt.

It’s not just the humor, though. Violent Solutions to Popular Problems offers bucketloads of glorious sentences. I remember a discussion with a friend who insisted that every sentence, every word, needs to serve a purpose for the story’s larger plot, that a character did not simply do something but had to do that something for a reason. Then what, one might wonder, is happening in Nabakov’s Ada or Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway? What’s wrong with reveling in a good sentence, created for the sake of it being a good sentence? Nicholls, fortunately, seems to cherish, to love assembling language. Check out some of the following, for example, pulled more or less at random from the book:

In our pell-mell, consumerist hellscape, the things designed to give us pleasure often cause us the most pain.

Inside rooms contoured to provide the least stimulating sensorial experience, with antiseptic airless bunker-like chambers modelled on the enhanced interrogation rooms at Abu Gharib, the couple were separated and made to complete questionnaires on each other for phase one of the authentication process.

As I waved howdy-bye to the pretty parchlands of the rural and the sweaty honk of the urban, I reflected upon my experiences with the abortion Ubers, the executors of mass shooters, and the peculiar lawyers and doctors making their plays in the land of plays. It was apparent that America had become intellectually clotted in the faulty vesicle of its own mythology.

Nicholls, I’d argue, wants us to remember how much fun it is to play with words, to show us just how far the English lexicon can twist and stretch without snapping.

While I admire Violent Solutions to Popular Problems the most for its wit and wordplay, I am happy to say that it does have something to say about the state in which we in the twenty-first century find ourselves. In the book’s second story, for instance—“Heath’s Ledger” (haha, yes, I know)—the narrator jumps right into a rant about advertising and consumerism, how the pleasure promised by, say, a massive billboard in which Kate Winslett hocks perfume is a bait-and-switch that in fact only brings pain. Soon enough, we learn that the narrator is afraid of experiencing too much pleasure and keeps a daily tally maintaining his pleasure-vs-pain equilibrium. Thus, when he finds himself in a highly pleasurable sexual relationship with a coworker, they quickly introduce pain into their physical relationship in a way that might leave the Marquis de Sade roiling in his grave. It’s funny, but the story is also asking questions about our fears, both of pain and of pleasure. In other words, Nicholls is far from being apolitical; it’s simply that his politics coexist with humor and artistry.

As if to demonstrate his ability to blend social critique and creativity, Nicholls includes “man/woman” a story told from the point of view of the “Subspecies Control Bureau,” who are adamant in maintaining particular gender and heterosexual norms. It is a story told through two columns, one with a traditional bathroom-sign male over it, the other female, with a warning above from the narrator, stating “Men: please follow the narrative on the left. Women: the narrative on the right.” And this preceding “The State of Texas: A Travelogue”—a Pynchonian tale about abortion in Texas that includes the wonderful sentence “Americans in America hollering at other Americans in America that they are unamerican traitors for making the slightest criticism of anything remotely American.” All of this is experimentation writ-large, not so much the postmodernist (or Modernist or Romantic or…) showing off of one’s cleverness, per se, but instead the basic desire of the artist to see how far they can push the art form, to see what can constitute a story, a narrator, to say nothing of how one might arrange words on a piece of paper, all the while challenging some of the worst aspects of our 21st century collective character.

It seems as if, though, Nicholls saw me coming a mile away. Perhaps he just set me, and people like me, up, wanting to have a laugh at our expense after inviting us to laugh at his expense for so many pages. Midway through the book, having already begun mulling over many of those thoughts re: postmodern playfulness that this essay began with, I ran into “The Pomo Martyr” and realized just how hyper-aware Nicholls—who by this point in the text has already had multiple characters reference him and his previous works—and his fiction truly are. Here, his protagonist talks excitedly about picking up a Gilbert Adair novel and “fellating the book on a four-hour bus trip” because it “chimed with my fondness for attention-seeking and making a fool of myself in a comedic way to drum up readerly affection for me through prose.” But that attempt at drumming up “readerly affection” works, and though the narrator soon finds himself deemed insane and locked up, he has become “a hero in the postmodern community,” a community which seems to comprise all the residents of his Scottish homeland, where basically every writer is soon writing in a postmodern style, as it is all the people want to read. He has become a sort of folk-hero prisoner, trapped by his own playful creativity, yet still devoted to the work, to the point that he writes with his own blood in his cell.

When I think of these stories as a whole, what I find myself pondering, beyond the humor and self-referentiality and alliterative word play, is the ancient Israelite prophets, who would often talk about a remnant, those who did not follow simply because the rest of the group was going a certain direction. The remnant Nicholls belongs to is that group of writers and readers who still value creativity and playfulness, who still want to find joy in literature. Any author who can end his story collection with a story titled “The Bardo of Abandoned Characters”—which, yes, is exactly what it sounds like—has creativity to burn. And I bet he’ll be doing it with well-polished sentences and a grin on his face.

Violent Solutions to Popular Problems, by M.J. Nicholls. Montclair, New Jersey: Sagging Meniscus Press, August 2023. 148 pages. $17.95, paper.

Matt Martinson lives and teaches in central Washington. You can find his most recent fiction and nonfiction in the journals Lake Effect, Coffin Bell, and 1 Hand Clapping.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.