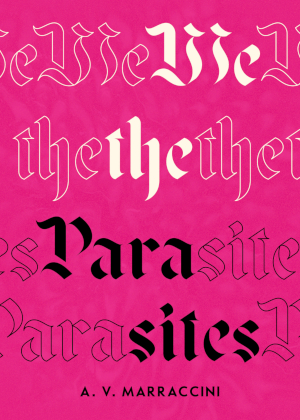

In We the Parasites, a five-part essay/memoir, A. V. Marraccini celebrates and critiques the acute, embodied experience of dedicating one’s life to admiring and critiquing art; the way we move through, haunt, and are haunted by the art that won’t leave us. But rather than locate this experience as solely intellectual, in the delivery of a criticism conveyed at a distance, Marraccini locates the experience of art in the desiring body. We need art as much as art needs us.

Marracini, an art critic and historian, argues that being a critic is not unlike being a female fig-wasp that pollinates a female fig flower. As she explains in the opening paragraph:

The fig is an inverted flower, which needs to be pollinated to make the fig fruit that we eat … Sometimes she [the fig wasp] crawls into a female fig, where she starves and dies, but in the process pollinates the inverted flower, which can then fruit.

The body of the deceased wasp is absorbed into the fruit, and fig lovers are none-the-wiser. And so the critic, in the act of considering the work of art, engages in this creative, queer pollination. In We the Parasites, criticism becomes a kind of compost, fresh soil in which new art can gestate and grow. Like a garden needs consistent tending to flourish, so art needs its human observers, its composters, its hosts.

On the late author John Updike, she writes, “I’ve already bitten off his tongue at the root and started to speak with it, stolen it like it was already mine, shadows playing on the empty vault of the mouth …” Marraccini, through the grotesque nature of art’s ventriloquism, recalls a violent sublimity to the experience of art that feels painfully lacking in our current culture where “art” (and criticism) is at the baseless whims of the market.

In Part IV of the book, Marraccini writes “I don’t kill my darlings in writing or otherwise … If I killed my darlings, there would be nothing left.” Of course by this point in the book, it’s difficult not to have already reached this conclusion. We the Parasites doesn’t offer airy scenes, brief spells of “casual” prose that some would argue allow more pointed lyricism to shine or impact. The book is dense, and nearly claustrophobic. It successfully places us in the crawlspace between fig flesh and wasp.

But if you appreciate a poetic line, you’ve come to the right book. One recurring artist in the book is Twombly, an American painter, sculptor and photographer who came to prominence in the 50s. His work engages heavily with classical myth and allegory, and Marraccini beautifully renders the timelessness of his work, weaving it throughout the narrative in figurative loops that mirror the infamous, obsessive loops recurring throughout Twombly’s body of work: “Did you know some mosquitoes numb you before they bite, so you don’t slap them? … That in the same part of the painting there is a first, light red scrawl, like a wound, like a dimestore lipstick kiss red?” From Twombly to Marraccini, to the book in our hands.

When I finally decided to google some of Twombly’s art (I’d never heard of him), I couldn’t see what Marraccini sees. (Not that I expected to have the same experience of a painting through a screen that I would in-person.) But if part of the point of ekphrastic nonfiction is to inspire even the attempt to connect with art on our own, then Marraccini succeeds.

She taunts: “Have you bought a copy of The Centaur already? I have infected you, too.” Though I don’t have a copy yet, it’s an anticipated addition to my reading list.

We the Parasites, by A. V. Marraccini. Seattle, Washington: Sublunary Editions, February 2023. 182 pages. $18.00, paper.

Lily Blackburn is a writer and editor based in Portland, Oregon.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.