There are a lot of different ways of being poor, and I have tried out several. I don’t want to oversell it. I’ve never lived on the street or anything. I’ve always had a safety net—parents who love me, and wouldn’t let me fall off the map without a fight—but there were definitely years when I was working two minimum wage jobs—14-hour days, seven days a week—just to make rent on a studio apartment or a shared two-bedroom in a town where neither should cost half what it does. Years when lousy (see: nonexistent) planning, reckless debt, and numerous deleterious habits kept me in a paycheck-to-paycheck cycle of depression and go-nowhere lethargy I had neither the will nor the wherewithal to break. How could I go anywhere, after all, when I could barely afford gas (much less food or lodging)? And when even minor repairs to my car—say a blown tire or a dead battery—could easily prove catastrophic to my already airtight budget? I just wanted to write for fuck’s sake. It had never seemed like a complicated goal. And yet, despite two shiny new BAs, I quickly realized I had no idea how to go about it, or to navigate the real world in the meantime; how to do much of anything more than try and get by until I figured it out. So no, I’ve probably never dipped below the official poverty line, but the first half of my adult life was definitely spent on or near the margins, and MadStone is all about life on the margins.

The denizens of Madiston, a Southern coastal city of otherwise indeterminate statehood, are not exactly thriving within their various intertwining ways of being poor. The most stably employed among them work at the local art museum (housed in an old plantation, as Southern institutions of distinction so often are), and even there are tiered after the familiar, frustrating patterns inherent to late stage capitalist America. There’s Bennie, the aspic-spined boss whose omnipresence puts everyone ill at ease, but is really just a symptom of his own cowardice in the face of going home to his wife and newborn child. There’s Rohaan, the recently promoted head of security—a slow-motion trainwreck of recovering/relapsing alcoholism and all-around master self-saboteur. There’s Buck, a floundering artist whose been hacking away (sometimes literally) at the same three paintings for years, perpetually yo-yoing between thinking they’re either too bad or too good to show to much of anyone (this while Jess, his camgirl-with-a-heart-of-gold partner, goes to increasingly girthy lengths to support his lazily deferred dream). There’s Aura, a migraine-afflicted survivor trying to outrun her abusive mother and the voices in her head long enough to start a new life with her lovable lunkhead Derek. And finally there’s Shareece, a middle management lifer who’s seen it all, and mothers the lot (including the recently laid off Carl, a reclusive autodidacademic fast descending into his own private, philosophical Hell).

The museum itself has fallen on hard times, and is shooting its moonshot on a mysterious installation piece in hopes of keeping the antebellum chandelier lights on one more year. And other than trying to string a few good days together between them, the ramshackle cast of MadStone are all pretty much just biding their time until that much-ballyhooed deus arrives ex machina. Enjoying a rowdy group bender here, “fucking the sheets off the bed” there, blearing together their waking and sleeping hours via the soft connective tissue of blackout, “tak[ing] care of one another in the throes of carelessness,” keeping one eye on the stars betwixt the slow-gathering storm. They dream about better futures, sure, and occasionally make feints at pursuing them. But by and large they’re stuck, and just waiting for something larger to come around and unstuck them.

If all that seems like more summary than I usually do, trust me when I say that I wish I’d had this handy-dandy guide to consult during my first venture through MadStone (I had to read it twice just to feel comfortable writing this article). Jost, you see, is something of a stylistic wizard, conjuring vivid, parlous plot out of all this lived-in plotlessness as he flits between narrators, past and present tenses, and first, second, and third-person voices like a roving horsefly on the paint-peeled wall. Likewise, his grasp of colloquial slang, dialect, and that rarest ineffability of all—“how real people talk”—feels both deeply true to our humid, shitkicking present, and wholly out of time, suggestive of late, great masters like Hubert Selby Jr., Zora Neale Hurston, and even William Faulkner. And all that’s without even getting into Aura’s and Carl’s respective joustings with the historic magnitude of Shakespeare and the self-aggrandizing Thermopoetic criticism of the (fictitious) Dermot Putsch (though both authors prove less than useful with regards to the immediate here-and-now, Jost uses them to great intertextual effect in depicting the ways that reading “important” books that you don’t entirely comprehend can still get the brain moving and shaking and breaking new ground). Needless to say, this is all heady, untamed writing that demands to be read slowly. If you try to rush or get ahead of yourself, he’ll lose you amidst thorny thickets of sweaty, poetic prose, only to spring up like a boxing-gloved jackrabbit and throw a sharp, well-crafted left hook.

Jost cuts to the matter’s soft, pithy heart again and again, such that you can’t help but see your own circumstances in every one of his characters’ plights (or, at the very least, see just how scant and precarious the ground separating you really is). His best lines hit close to home while you’re reading, malinger around your property till you finish, and then, sure enough, find their way to living rent free in your head long after you’re done. As for the mise-en-scene in this book, Jost writes broke and busted masterfully. The stains. The smells. The secondhand everything that never gets cleaned or fixed or replaced because it barely worked to begin with, and you’re so far in the hole that nothing seems much worth doing anyway. It’s all there, steeped in the low-tragic tradition of down-and-out ensemble dramas like The Connection, The Lower Depths, and La Boheme. If all this is starting to feel like more comps than I usually make, it’s only because I don’t believe I’ve ever read an author anywhere near my own age who writes like this (indeed, the 82-year-old John Edgar Wideman is the only living example I could even come up with). And despite all those lofty comparisons, rest assured that Jost is still doing something breathtakingly unique—bringing these wearily age-old conditions to bear on the gig economy working poor of today (and establishing Madiston itself as a potential Yoknapatawpha to call his very own). From the Cobbles to the Jaspers, and the junkies pacing Harris Park end-to-end, the teeming, crumbling, striving climes of MadStone evoke a term more often associated with high fantasy or sci-fi epics: worldbuilding.

And exactly what kind of world we’re trying to build, is perhaps the question that looms largest over MadStone throughout, hovering like the violent weather system that invades the final act. What does it mean to help the poor? To live in a fair and free society? To promote “the American Dream”? After all, as no less than our nation’s heartless last President once put it, these characters are “no angels,” and who among them you find sympathetic will vary from reader to reader, but they are, whether we care to acknowledge it or not, all undeniably victims of a certain amount of institutional bullshit. They’ve been stacking unlucky breaks since birth, and their at-times-infuriatingly cyclical straits—their endless running hamster wheels within hamster wheels of love and abuse, art and commerce, supply and demand, fantasy and reality, stasis and change— “Same as the same is the same as”—are, in many ways, the real stars of MadStone’s big, first floor gallery show. Systemic injustices chronicled so incisively as to be rendered sentient and corporeal. Even the vaguely hopeful denouements some of these characters achieve still feel beholden to higher forces in subtle, unnerving ways—just new variations on the same old hamster wheels. So how did we let the world get this way? MadStone seems to ask. And how do we fight them, these injustices that have grown too big to fail? Too all-encompassing to escape? Or, as Jost writes himself near the end, in a voice that sounds less authorial and more compatriotic—like he knows these struggles of which he writes so beautifully—“How then are we meant to go on living?”

I don’t consider myself poor anymore (though by many peoples’ definition I probably still am). After several years working a no-collar, graveyard shift job delivering newspapers (remember those?), and several more bouncing around various dying retail establishments (remember Borders?), my big break came in the form of an entry-level staff position at a University Library (likely very similar financial circumstances to the staff of the Madiston museum). My wife and I are, after misspent youths of artistic striving, semi-comfortably lower middle class. But America is getting harder every day, and the margins are never as far away as you think. We’re both lucky, and well aware that a few unlucky breaks is all it takes. And the best answer I have as to how we go on living is just that we do our best, for ourselves, and for others. We try to help, even when there’s no help for it; to fix the systems beyond repair; to “hope against the dam.” To refreeze the icecaps and replant the rainforest; to not give up or give in or go gentle or concede to “already too late.” We try to make art that matters, even when it feels like nothing matters. That’s what I try to do, anyway. And it’s what I think Jost is doing too. His is a young voice, with an ancient soul. He may write like the world is ending, but he’s still got all the time in the world.

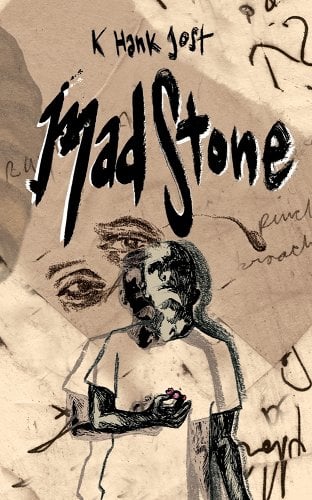

MadStone, by K. Hank Jost. Whiskey Tit, November 2023. 302 pages. $20.00, paper.

Dave Fitzgerald is a writer living and working in Athens, Georgia. He contributes sporadic film criticism to DailyGrindhouse.com and Cinedump.com, and his first novel, Troll, was published in May 2023 by Whiskey Tit Books. He tweets @DFitzgerraldo.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.