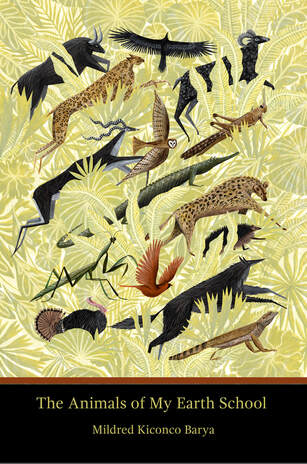

The Animals of My Earth School, by Mildred Kiconco Barya, is a collection of poems about animals, surveying a few of the characteristics that they share with people and calling our attention to what we might see if we try looking at the world from the eye level of other kinds of creatures.

Barya, originally from Uganda, is currently an Assistant Professor at UNC-Asheville. Her publications include Give Me Room to Move My Feet (Amalion 2009), The Price of Memory after the Tsunami (Mallory International 2006), and Men Love Chocolates But They Don’t Say (Femrite 2001). She is on the board of African Writers Trust, and coordinates Poetrio Reading Events at Malaprop’s Independent Bookstore and Café in Asheville.

Although we are put into a childlike situation–being schooled–these are not beast fables with talking animals or largely metaphorical animals like Blake’s Tyger, Tennyson’s Eagle, or Delmore Schwartz’s “The Heavy Bear Who Goes with Me.” The animals and insects in these poems are realistic and closely observed, as in the poems of Mary Oliver and Emily Dickinson.

The volume is divided into five sections: Insecta, Mammalia I, Aves, Reptilia, and Mammalia II. Although the classifications are specific, they don’t go any further into taxonomy by identifying which of the 41 orders of aves, for example, are featured in each poem. Barya’s sections present us with levels of sight and corresponding levels of insight into human life and art.

Looking at the world from the point of view of a giant stag beetle in the first poem, the speaker declares that “to know you is to go underground” and “you stridulate and give off sounds and eat ginger.” The most easily observed features of the beetle are described, but in the end “you remain a mystery.”

The mystery of human urges is examined by observing an insect in “Coccinellidae,” about ladybugs:

For some reason, the bug reminds me of my ex. Small head and

tiny legs dragging along a large body. I could squash it between

my thumb and index finger. The thought doesn’t startle me. I

recognize it in the same manner that a mug of hot

coffee holds the capacity to cause damage, and yellow jackets on

my favorite trail probably entertain similar thoughts. Perhaps, it’s

the recognition, rather than mere

compassion, that prevents any one of us from testing our limits.

Focusing on insects reveals anxiety about the future, as in “Music” when imagining a world without the sound of cicadas reveals it would be “a world without Joy / marking the end of / underground movement.” Looking at ants makes the speaker of “The World Is Necessary, Even for Little Ants” ask “do humans / have the means to live differently?” Even thinking about the mantis in “Heads Are Unnecessary for Copulation” spurs the speaker to

Imagine what humans could do with such stimuli and perception

of depth. Like old gods, they’re always hungry, fierce, and

bloodthirsty. Crossing from praying to preying

when they find a willing sacrifice.

Focusing on animals can reveal hidden aspects of our own nature. In “Moon Dog,” for instance, a poem about wolves, we learn that “everything human and animal vibrates in you: / violence, intelligence, hot sex, insatiable appetite.” And indeed, it seems that we’re like wolves when we read “Ode to the Sheep” because “the meat is great, / but that’s not what / this is about. We kill / for texture.” We’re like the Etruscan shrew, “the living mammal with the smallest heart.” Seeing a newborn calf in “Guilted Tenderness” makes the speaker think “we / were all once like that, newly born and helpless.”

In contrast, in poems like “The Human-headed Lion Seduces Three Lambs,” the speaker sees how attractive danger can be. Looking at “a lion with a human head enticing three lambs” she observes that instead of running away, they

gaze at the lion’s face. Have you ever looked into the dilated pupils of a lion’s eyes? They’re filled with peace and light. Ambered appetite. Persuasion. The lambs enter the land of believability and walk with the lion. We know he’s going to eat them; he wants to fatten them for his own good.

Similarly, in “What’s Not to Love” a leopard is a “distinguished strategist. Ravenous. / He’s all claws and rosettes, ready / to consume and make the elderly sigh.” The poet’s observations seem commonplace when it comes to big cats; both of these poems remind me of the memes about Americans who voted for the “leopards eating faces party” in the presidential election of 2020.

Thinking about levels of seeing is especially important when watching birds and squirrels, who are often above human eye level. “Little Wren,” for instance, sees the world from above, and “we speak our hope to see you in flight. / Grandma says,” wanting that larger perspective on her own life where “she thrives amidst sorrow and grief.” The cardinal in “How Can It Be a Cardinal Sin” sees something other birds don’t see while the speaker of the poem surveils him: “that cardinal over there in the rhododendron hedgerow is in love with a robin. I witnessed their courtship while sipping Earl Grey tea on my porch.” And in “The Earth is Unfinished. So Is Everything,” a squirrel is “jumping / sideways from tree to tree” and the speaker says

I’ve been told squirrels remember only 10

percent of where they hide nuts. How

nutty. Though the same is said of humans’

brain capacity. The rest, latent, burns or is

buried with us when we die. At least, the

squirrel is skilled in gymnastics.

Constantly views the world differently.

By the end of the poem, the speaker promises to “return home and fall on my knees, / take my beloved’s hand, and pledge to stay / as long as I remember where I last left him.”

The idea that humans can learn from watching birds is central to “Relentless Play: The Nature of Struggle,” in which four crows seem to be tormenting a baby owl. The human who has been watching says, towards the end of the poem: “It’s dawned on me that while there’s struggle in the nature of all that exists, there’s also unmistakable fluid grace, skill, and bold engagement. Heated tension, yes. But in my human relations, under similar pressure, do I hold myself back in honor of something greater, like dignity? Haven’t the birds demonstrated that their existence—like their struggle—isn’t about insult or assault but relentless play—albeit frenzied?”

One of the things we learn from animals is their routines, like “The Graceful Alligator” who “glides gracefully past our home by the canal” each day as “we watch from the bank as it moves in a straight line, joyful to see it once more, to anticipate its comings and goings.” And one of the things we’ve failed to learn, according to “Factors,” is that “when we discarded our tails as Homo sapiens, we were supposed to swallow them in order to keep our reserves intact. We forgot a significant part of ritual and opened ourselves to disease, predators, and a weaker immune system.” Something that the speaker of the poem “Dream of Lizard Solidarity” has failed to learn is “to take life less seriously.” She has “disappointed / humans before. / Now, lizards.”

The most important thing we learn from animals, according to this volume, is how to look at the world in order to make art. Addressing a serpent in “Dear Serpent,” the speaker of the poem declares “I am an artist / looking at you.” In “The Hyena,” we need to “return to the laughing / hyena state in which we once knew all that we needed to know— / females come first. Patriarchy is dead. Nothing else matters” and “we must retrace our sharpness and / wholeness not in science but in the sounds and silences of our / drum circles” in order to feel, to “heart-think,” and to express those feelings in a way that makes sense and resonates with others—especially those who value animals enough to try seeing the world from their eye level.

The Animals of My Earth School, by Mildred Kiconco Barya. West Caldwell, New Jersey: Terrapin Books, April 2023. 96 pages. $17.00, paper.

Jeanne Griggs is a reader, writer, traveler, ailurophile, and violinist in the Knox County Symphony. She directed the writing center at Kenyon College from 1991-2022. Jeanne earned her BA at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, and her doctorate at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her conference papers include “A Survey of Reanimation, Resurrection, and Necromancy in Fiction since Frankenstein,” and “Climate Change Predictions in Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents.” Published by Broadstone Books in 2021, Jeanne’s volume of poetry is entitled Postcard Poems. Jeanne reviews poetry and fiction at Necromancyneverpays.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.