George Perreault’s lie down as you were born not only makes a song of grief, but peoples a town, grows a forest, seeds a sky, and weaves a myth in threads of sorrow. I was so immediately taken with these poems, pulled in and not allowed ransom. In these poems the voices of father, mill worker, veteran, drifter, husband, and elder emerge from the music, inextricably tied to the land they were born and which they will return. This is a lament and a prayer for the dead, dying, and still breathing in the dust inside of our ancient rooms. And even though Perreault encapsulates so much territory and history in his poems, they still seem crystal clear, vibrant but beautifully invisible, a tune you forgot you remembered, the needle setting down on the record and hissing with small earthquakes. Perrault has felt loss and he opens up to us with tender honesty in the poem “prayer for my daughter”:

i can’t go into Starbucks, have to sit and weep

in the car unseen … as i look for my own

open road while the floor clots with tissue,

winter hills hazy with rain, my wife knowing

how the dead girl has dredged me again.

Anyone can feel his torture as he mourns his child, yet it elevates in the next stanza, as he wishes her “more / than soft weather … the river accepting what it can from the sky.” His “ordinary anguish” is transcended in these verses and we all are taken to a place of hard-won solace. He ruminates on the death of five kids at the high school, the overdoses, the murders, the traffic accidents which take and he states he is “trying for the long view today,” even though “there comes a time Amazing Grace will / make you sick to your stomach.” He tells his children, even himself “how death hunts us, kid, like rustlers, / like thieves,” but to “listen in those deep ravines where the night / cries out with a music so like our own, songs / to shoulder each other’s pain, songs that / without an us there’s no reason for a me.” There is something extraordinary in these alchemies which turn our bile to silver in how we retell the darkness.

These poems are always surprising, always getting lost and refinding themselves miles distant on a desert road:

… so I wasn’t lost exactly, knew

ten miles north were tracks amid scattered shards of

native shelters, then ten more to pavement, just

a five hour walk without food or water …

His words always find their way back, although the words themselves offer to real safety: “—each day / in the garden, naming, naming as if words / are ever enough, as if when the circus has / passed, some hand will take from me a rib.” Or as he states in “among the wabanaki,” “a language where nothing’s other than / verbing, intransitive to the core, // no growth only growing, / only wonder, only cease.” Every golden realization can be undone by the words which form it, and Perreault is a master at constructing and deconstructing simultaneously.

His words also take us into a small town where a woman’s body is found in pieces and the murderer is a neighbor, realizing that “killers aren’t raised by wolves, and this one’s / little sister’s in school with us, a quiet kid and smart, / though her name’s no longer hers alone.” He takes us under a shady tree where a man recently lost his son to a heart attack at a little league game. He takes us to a foster home where there is a kid with chemo, a kid who saw her brother commit suicide, a girl with epilepsy, a boy with a sick mother who “believes / there’s a town we can get to – / … somewhere beyond broken / there’s acceptable loss.” He takes us to a mill where men toil until they die eating the same baloney sandwich every day. Every time the ordinary is devastating and the devastating is an epiphany; Perrault captures us in his voices and in his fragile hopes.

Perreault begins the book explaining how we are all “making our noisy way toward our own little sleeps.” In the course of this monster of a book he takes us through death, up to Olympus with the gods, through loss and dissatisfaction of all kinds, but always finds a way to make to make us bring up our tears and prayers, to stir us to “wail together now / till it yields a kind of joy.” And at the end of this collection he strings together a lyric music:

the dirt and rock we have kneaded into prayer

slept into caves warming as we sank down

with the one-mind of schooled fishes, slept

into the clip-clop of crickets and night frogs

and the moving bubble of silence where we become

the smallest numbers that ever were;

all of this and the butterfly flutter of bats and

crows calling darkly through another dawn,

i have slept and rise to sleep again.

Perreault’s book is an explosion and an ocean and a symphony and a dirge. Even though his words bring you out of your body they also reach for you in the silence and lure you back with a plainsong and a soft tongue. Not much you will read will reassemble all of your parts into such a broken and wondrous whole.

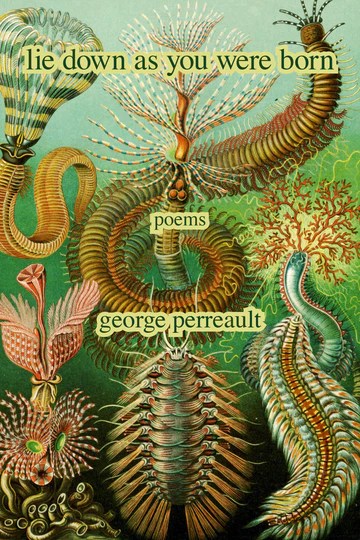

lie down as you were born, by George Perreault. Kelsay Books, July 2023. 100 pages. $23.00, paper.

Scott Ferry helps our Veterans heal as a RN in the Seattle area. He attributes his writing skill to listening to rain fall upwards from the bottom of a fictional aquarium. His most recent book, each imaginary arrow, is now available from Impspired Press. Upcoming in early 2024, his collaboration with the California poet Daniel McGinn called Fill Me with Birds will be published by Meat For Tea Press. More of his work can be found at ferrypoetry.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.