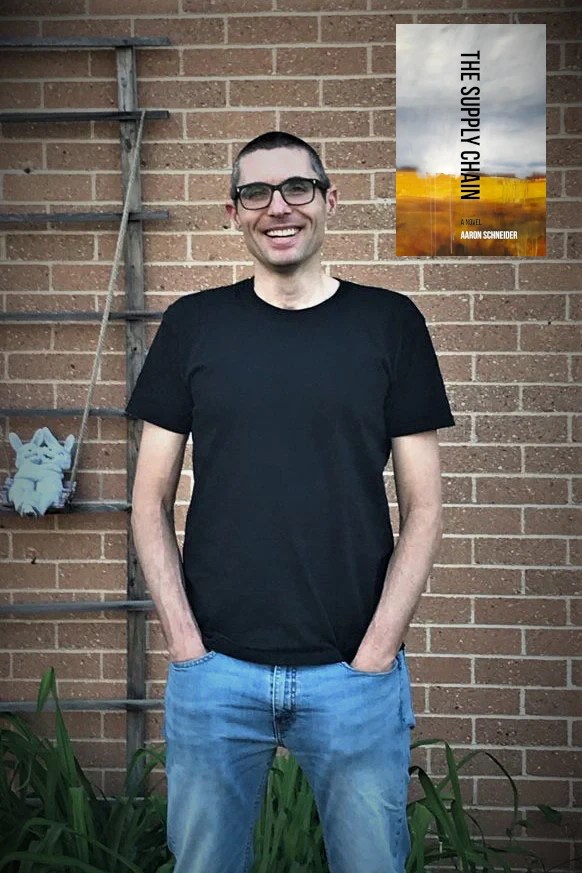

Aaron Schneider is a queer settler living in London, Ontario. He is the Founding Editor at The /tƐmz/ Review, the Publisher at the chapbook press 845 Press, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Writing Studies at Western University. His stories have appeared in The Danforth Review, Filling Station, The Ex-Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Pro-Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, BULL, Long Con, The Malahat Review, and The Windsor Review. His stories have been nominated for The Journey Prize and The Pushcart Prize. His novella, Grass-Fed (Quattro Books), was published in Fall 2018. His collection of experimental short fiction, What We Think We Know (Gordon Hill Press), was published in Fall 2021. The Supply Chain (Crowsnest Books) is his first novel.

The Supply Chain weaves a father’s emotional journey, poems, and found texts into an urgent and lyrical exploration of love, complicity, and the far-reaching consequences of average lives. For decades, companies have used London, Ontario, to test market their products because it is a quintessentially average North American city, and Matt Nowak is as average as the city in which he lives: he watches hockey on Saturday nights and football on Sundays. He has a job that he doesn’t like but that he was lucky to get. He has a house in a suburb that he can only barely afford, and a newborn son who he struggles to love because he was himself raised by cold and distant parents. But one part of Matt’s life is far from average: the company he works for manufactures the armored vehicles that Saudi Arabia is using in the war in Yemen, and that conflict, whose chief victims are children no different than his son, forms the backdrop to everything Matt does.

This interview took place over email during the summer months of 2023.

Andrew C. Wenaus: The Supply Chain is a novel that is as much about the abstract procedures of global logistics as it is about intimacy and empathy. The novel’s subtitle is “Versatility, survivability, lethality, and maneuverability.” What was the impetus or inspiration to write this novel?

Aaron Schneider: Like most books, it has multiple points of origin. The most obvious one is Michael Lista’s article on Scott Griffin, the founder of the Griffin Prize, that revealed that he had made his money as an arms manufacturer. Griffin owned a parts manufacturing plant that produced shock absorbers that were used in the Light Armored Vehicles that are assembled in the General Dynamics facility in London, Ontario. That article was the first time that I learned about that plant and what it produced.

The less obvious, and, in some ways, more important origin point was the realization that London was now my home, the place where I lived and where I was going to stay for the foreseeable future. It was a realization that I came to slowly, quite reluctantly and only after more than a decade and half in the city. London is a difficult place, a difficult place to feel connected to and to find a community in, and it is particularly difficult for people who aren’t from here. It is a city that shuts people out, and one that holds its history, its identity close. It is not so much a city of secrets as it is a city of silences, of assumptions and forms of understanding and connection that you have to grow up with to access, that you can grow into if you are from elsewhere, but only slowly and always incompletely. This makes it sound more romantic and mysterious than it is. Really, it’s a run of the mill Southwestern Ontario city that has not yet forgotten that it began as a small town. The book grew out of an ongoing effort to understand this place in which I have found myself. The intimacy and empathy is part of this. Communities can be mapped, charted, surveyed, we can bring these complex apparatuses of measurement and analysis to bear on them, and what we learn when we do this is invaluable, but they are first and foremost experienced as an affect, and there are substantial portions of the book whose aim is to unfold that affect, to present it to the reader as an experience they can share, and, perhaps in a limited way, understand.

The juxtaposition of that intimacy and empathy with the abstract procedures of global logistics is a reflection of the focus of the book: arms manufacturing is a central pillar of the city’s economy, and it touches the lives of people who live here in countless, often barely perceptible, and quite intimate ways, but it is an industry that is indisputably global in terms of both its production networks and its impacts. The vehicles manufactured in London have been used in the war in Yemen, a war on the other side of the world whose only connection to most of the people who live here is these vehicles. A decade or more ago, I read Ernesto Sabato’s The Writer in the Catastrophe of Our Time. In it, he writes about the novel having this special ability to reconnect the spheres of science and the arts. I don’t want to rehearse his argument, and its specific points are less significant than what I took from it, which was that fiction has a unique capacity to draw together and articulate the connections between the particular and intimate contents of individual lives and the abstract structure of world spanning systems. I don’t know if that’s the case or whether it’s a fantasy I’ve chosen to believe in for fairly obvious reasons, but it has conditioned the way that I think about the novel, and, specifically, how the novel can respond to and engage with this moment in history, one characterized by what seems to me to be the increasing clarity with which the emotional world of the individual subject is implicated in global systems, whether they be logistic, economic, political, or climactic. The book is an initial attempt to explore/activate these possibilities in the novel, and to map these linkages, not with a cold objectivity, not as an academic exercise, although these kinds of exercises are essential, but in a way that preserves the intimacy of subjective experience while placing it within the larger systems it is conditioned by and shapes in turn. It is, in simpler terms, my attempt to understand the lives of Londoners who live and work as Londoners and who, in doing so, touch the lives of countless other people around world, to understand people who are perfectly normal everyday people whose lives and work are contributing to the ongoing humanitarian disaster in Yemen. In this respect, it is very much a book about empathy, and the limits of empathy, about how the consequences of our lives reach beyond the geographical boundaries of our empathy. Who do we care about? When do we chose not to care, not to know? And how is it that we manage/rationalize the limits we impose on caring?

ACW: The protagonist, Matt, works for a defense and arms corporation’s Supply Chain Management Distribution and Logistics Division. He repeats the company’s unofficial mantra to himself: “This job is about people … it’s about developing and maintaining relationships.” These relations are mantras of ethical denial on the one hand and honest—if euphemistic—repetitions acknowledging the importance of communication being subsumed by global logistics on the other. In other words, there are several supply chains, or chains of relation, in the novel. There are five levels of networks or relations operating in the novel. I’d like to ask you about each: global logistics, local setting, family intimacy, the act of writing, and the interplay of form and content. We can talk about each level consecutively. The first supply chain is literal: the defense contractors and the arms trade. This is a profoundly inhuman mode of communication: it is an abstract network designed to outsource hypercomplex—often highly delicate—exchange networks across nation-states. These are networks of optimized efficiency and speed. While it may seem obvious that this is no way for people to relate with one another on a day-to-day basis, the philosopher of speed and war Paul Virilio, quoting a statement from the Pentagon from the late 1940s, remarks that “Logistics is the procedure following which a nation’s potential is transferred to is armed forces, in times of peace as in times of war.”[1] A nation’s potential is another way of saying the potential of an aggregate of national subjects. And this kind of communication finds itself implanting into everyday interpersonal communication. In other words, according to this line of argument, even civilians are communicating with one another according to the logic of war. Could you share a few words on how these abstract relations play out in the novel and the psychological effects that they have on the characters?

AS: I like the way you use Virilio here. I hadn’t thought about it in these terms, but this gets at something that I was trying to explore with relationships in the novel. As I was writing the book, I thought about it as an instrumentalization of personal relations, as the logic of profit and the commodity invading and conditioning the connections between characters, but this is, in many ways, identical with the logic of war. It’s one of the reasons that I included swimming in the book. I love sports, and I used to love competitive swimming (I destroyed my elbows so I can’t do it any more), but the camaraderie of competition is balanced by its corrosive, atomizing effects, by a remorseless logic of leaving behind the slow and weak in favour of the fast and strong. I don’t want to push this too far because I don’t want to end up sounding like one of those half-drunk barstool pundits who are happy to explain to you that football is really a barely sublimated form of war, but the logic of competition as expressed in sport is very close to the logic of war and entails a reduction of people to means.

There is a scene towards the end of the novel when Matt’s boss sits him down and explains to him that he is underperforming. He talks to Matt about the workplace being structured by what he calls “conditional love”—it’s a term he has taken from coaching, and it describes the underlying ethic of a competitive team where members need to earn their spots. The way this ethic mobilizes love in the name of what is effectively an exploitative instrumentalization of people is obvious. What I find more interesting is how this logic is isolating, how the reduction of people to means locks them into themselves, forces them to be self-interested, and limits the extension of their empathy.

This is explicit in Matt’s workplace, but it is not a logic that is limited to the arms manufacturing industry, rather it precedes and underlies it—it is, although I don’t know how committed I am to this statement, the condition of that industry’s existence, and it certainly the informs the ease with which people in the industry discount the impacts of their work. The core conflict of the novel is Matt’s inability to love his newborn son, to create an affective connection that extends beyond the narrow container of himself. This is, in part, because he works in an industry and an environment where people are not ends but means, and love is a managerial tactic deployed to increase productivity, but it is also and more importantly because that environment is not new to him. It is the environment into which he was born, in which he grew up, in which his understanding of relationships was formed. He is the son of cold and emotionally withholding parents who are cold and withholding because they are more concerned with themselves and their careers than their son. In that respect, they are no different than Matt’s boss—their love is conditional, and rigidly limited.

What the book attempts to explore is the very real and urgent possibility that, rather than being the isolated product of the arms industry, of military institutions or conflicts, the logic of war pervades contemporary society, determining relationships and how people, even people who love each other, communicate. If the book has a premise, it is that this logic is not so much produced by this industry, as it allows this industry to exist, and the book works to tease that out through Matt, his relationship with his parents and his boss, and the connection he struggles to build with his son.

ACW: While abstract global networks offer the constitutive or broad conceptual setting for the novel, its actual setting is London, Ontario, Canada. The city isn’t often used as the setting for a novel. Yet, it shares something in common with the entirety of the Americas: it is a place with a history of colonization, subjugation, and mass genocide. This brings us to the second level of relation: the historical relationship that London, Ontario, has to its namesake: London, England. The fictional company for which Matt works in London, Ontario, is based on an actual a manufacturer of tanks and armored vehicles based in London: the General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) plant. While the core of the novel’s critique is based on this workplace and its psychological effects on its management, employees, and some of the city’s population, the novel also concerns itself with local history, particularly colonial and war monuments. While the European colonial era is technically over, it was replaced by an equally devastating and violent imperial era. Just as British London was a center of global subjugation, exploitation, humiliation, and mass murder, so does London, Jr. follow in its father’s footsteps: a global node making possible global imperialism. What you’ve done here is crystal clear and potent: could you say more about London, Ontario as a setting for violence and dehumanization? And as a setting for possibility, kindness, empathy, and reconciliation?

AS: London, Ontario is, at least superficially, a nonplace. I have joked that it is four exits on the 401 that no one takes—people who are from London tend not to like this joke, but people who aren’t from here get it, largely because they’ve driven past those exits without taking them. It occurred to me recently that London is a fairly large city, over half-a-milling people at this point, but it lacks at least one of the key markers of a city’s identity—it doesn’t have any landmarks to draw people to the city. No one comes to London to visit this or that place the way they do with other cities. It isn’t known for anything in particular. It exists, in some ways, as a generic city. In fact, London has a long history of being used for product testing because it sits so close to the baseline North American average, because it so generic, because it’s a kind of every-city. So, there is a way in which London’s lack of identity makes it a perfect entry point into thinking and writing about larger socio-cultural issues.

That said, for all that it can look like a nonplace, like everywhere, it has a history of its own, and, if you take the time to look, to dig, and you have to dig because it’s a history that is often ignored or forgotten, what you discover is fascinating. I can talk for far too long about local history—about Colonel Talbot, the figure who controlled the settlement of the region for three decades, about the city’s late nineteenth century incarnation as an oil town and its connections to global warming, etc.—but what interested in me in writing this book was the depth of its connections to the military. London was initially conceptualized as the capital of Upper Canada—what would become Ontario—and it had a garrison stationed here in the 1830s. That garrison was actually located in what is now Victoria Park, the park at the center of the city. There has always been a military presence here, and that is most obviously reflected in the monuments of Victoria Park. With the exception of the Women’s Memorial, a memorial to the victims of the Montreal Massacre, all of the monuments in the park are monuments to war. To be in the park is to be quite literally surrounded on all sides by the celebration of martial heroism. There are monuments to the First and Second World Wars. There are cannons from the Crimean War. And there is a particularly large and imposing monument to the Boer War. What I found and continue to find fascinating about this is that these monuments are simultaneously indisputably present and just as indisputable invisible in some very specific ways. The best way to understand what I’m getting at when I say this is the responses of people to me pointing this out: more often than not, when I tell someone that there is a monument to the Boer War in the park, their response is surprise, but, when I tell them where it is, they immediately recognize what I’m talking about. The monuments have a sort of ghostly presence, existing as material objects, lumps of stone, bronze, steel, that people see and register when they walk through the park, but as material objects that fail to signify in crucial ways. From this perspective, the monuments provide an opportunity for thinking about the elements of a particular context, elements of the lived experience of Londoners that are immediate, definitive, and unseen.

You ask about possibility, kindness, empathy, and reconciliation, and all of these things are important, but I would like to stress that they need something very specific to precede them. I think about these things as a settler, as the beneficiary of colonialism, imperialism, etc., and I think that, as a settler, I have a set of responsibilities. One of these responsibilities is to critique the institutions that I have benefitted from, to turn whatever power I have back on them. This critique needs to precede the turn towards more positive kinds of work. In the context of London and in the larger context of Canada, it is a critique that has only barely begun, and which remains largely incomplete. It’s why I tend to think in terms of producing a literature of accountability, one that often involves literal accounting—itemizing the monuments in Victoria Park, making them visible as ideological constructs as well as material objects, for example—a literature that is analytic, rather than forward looking. This is also, I have to admit, a personal predilection. I’m a pessimist by nature who struggles to be positive. That said, there is possibility here. I find it by engaging with the place itself, with the river, in particular. There is a passage in the novel in which Matt stands by the Thames River, the river that flows through London, and watches the water. This is something that I do often. He doesn’t find any solace in it, but I do, and I also find that, at least for me, engaging with the river is a way to begin to inhabit this place ethically, not without thinking critically about what I am doing, but in a way that allows me to begin to see the kindness and possibility in this place. I’m working on a number of projects about the river that fold together scholarly work, art, and writing. They’re in their early stages, but I’m hoping to use them articulate more fully what I’m getting at here.

ACW: Since London, England is the “parent” of London, Ontario, let’s turn to the third net of relations. I’m wondering if you could comment on the novel’s emotional core: Matt, a former competitive swimmer, now alienated worker and abstract abettor of internationally sanctioned mass murder, has recently become a father who struggles to feel affection for his child. Yet, despite his work’s dehumanizing nature, Matt’s emotional trajectory follows one of cold rationality, full-out denial, and, eventually, love, affection, and openness. Could you comment on this trajectory and its thematic import?

AS: This emotional trajectory, and, in particular, its end point is my way of getting at the limits of empathy that are central to the arms manufacturing industry, to the people in London who are bound up with that industry, and, in some ways, to Canadian society more broadly. The book begins with an epigraph that briefly lays out the facts of the Dhahyan market bombing. In 2018, an aircraft that was part of the Saudi coalition fighting in Yemen, dropped a bomb on the market in the town of Dhahyan. The bomb impacted near a school bus carrying children returning from a field trip, and killed more that 50 of them. It’s a horrifying incident that has become emblematic of a war whose chief casualties are children. Matt’s inability to love his son is, at least from a thematic perspective, a way of pointing to the consequences of his work, to how the vehicles he helps to produce and distribute are contributing to that war and those deaths, and a way of bringing those consequences home to London and to him. His journey towards loving his son (sorry, this is a bit of a spoiler) is both a very personal one that has to do with his upbringing and his relationship with his parents, but it is also a commentary on the limits of care and empathy that I talked about earlier. I see it, and I hope readers will see it, as darkly ironic commentary on who we chose to care about and how easily we discount the lives of those who are far away and very different from us.

To me, what is most interesting about arms manufacturing in London is how it is rationalized. If you pay attention to the articles written about it and the rhetoric mobilized by politicians and business leaders, it is persistently justified along lines that are as much affective as they are pragmatic. We are asked to care about the workers, their jobs, and the families those jobs support. Matt’s emotional trajectory is a way of both exploring that. More importantly, if I have achieved what I wanted to, and I’m not entirely sure that I have, it’s a way of implicating the reader in that affective justification. The emotional appeals in the media are powerful and hard to resist, and I hope I’ve replicated them to some extent. I’ve had a few readers tell me that the book has a happy ending. I don’t agree. But I like the fact that some people have responded this way. It’s a measure of how easily we privilege the connections that are closest to us, to the people we live and work with, and to the character we have in front of us as we read.

ACW: The next level of relation or network I want to ask about is your relationship to writing the novel, the city of London, the research materials, characters, etc. Could you share some words about your experience writing the piece? Has there been any local grumblings, anxieties, conversations, or praise about your thinly disguised proxy for GDLS?

AS: I wasn’t sure what to expect when it was published. I was interviewed on the local CBC radio morning show, which reaches a fairly wide audience, so I think people in the city know about it. I haven’t received any pushback. I think that that is largely due to the fact that the book’s criticisms are relatively complex. I could have written something that was more programmatic and overtly condemnatory, and there is room for writing like that, but it’s not what I’m interested in. I’m more interested in exploring problems in fiction than I am in calling out moral failings, and the book reflects this. It’s not, at least overtly, an angry book, so I think it’s probably difficult to get angry at or about.

I have received some positive feedback about the descriptions of London, in particular about the opening passage that sums up the city and its neighborhoods. There has been very little written about London. This is changing. Books such as Erica McKeen’s extraordinary novel Tear are using the city as a setting, but this is a relatively recent development, and I think that part of what I’m seeing is people’s positive response to me engaging with the place. I really hope that this small wave of books mine is a part of grows, and that more people write about this place. Despite its superficial banality, it’s a fascinating place, and I’m interested to discover how other writers see it.

ACW: OK, the last of the five relations: form and content. This novel, somewhat uncharacteristic of so much contemporary Canadian Fiction, has frequent shifts between prose and poetry. These shifts do not feel clunky, forced, or sentimental. Instead, they often intrude into the narrative at instances of historical examination. Can you say more about this choice? Are the poetic shifts attempts at a more nuanced or truthful articulation? Or, are they sometimes, like we see in the poetry of Paul Celan, like fragments or shrapnel flung from a history so devastating that it resists prosaic articulation? What is the formal and thematic significance of these shifts?

AS: I have to begin this answer with a confession: these formal shifts are first and foremost a reflection of my predilections as writer. When something isn’t working, when I’m blocked or the words are falling flat, the way to unlock what I’m working on is to shift form, often to break open prose into poetry, or, at least, radically alter its appearance on the page. I’m not sure why this beyond suspecting that I have a fairly strong contrarian streak that makes it difficult for me to be comfortable in/with conventional prose. This mixture of prose and poetry is something I did in my first book, and some form of experimentation with form is a persistent feature of my writing because, at the risk of making what is a weird tick of my creative brain sound self-important, it’s an essential part of the writing process for me.

In the context of this novel, these shifts play a number of different roles. At times, particularly towards the end, they’re meant to defamiliarize the text in a way that reflects the extreme state of disorientation/detachment Matt is experiencing because he hasn’t been able to sleep for weeks. At other times, they’re a way of folding all the various dimensions of a complex, multi-strand experience together. For example, there’s a description of bush party that Matt goes to when he is a teenager that follows him and his friends from the swim team through the events of the night that is, except for the opening and closing passages, set entirely as poetry. It jumps from one person, one moment and event, to another in a way that could, I think, only work in the context of medium that is more accommodating of fragmentation than prose. So, in places like this, the choice to use poetry is a solution to technical problem. Most of the poetry is in the second section of the novel, which is really a bildungsroman contained within the larger frame of the book. The account of Matt’s growth and development is consistently interrupted with snatches of poetry and found texts that are often set as poetry. In this section, the poetry is very much fragments or shrapnel flung at the narrative of his life, not necessarily poetry that is poetry because its contents resist articulation through prose, but certainly because those contents are at odds with the straightforward narrative of his life. As I wrote the book, I thought of these fragments as eruptions of context, of moments when the personal is disrupted by the historical, political, economic, geographical, etc., as a breaking of narrative that is simultaneously the returning of that narrative to its multiple, invisible origins. I still think of them this way, but I think they can also be read in reverse, not as eruptions in the text, but as openings in it, as invitations to move beyond the confines of an individual life into the wider context that moves beneath and through it. They are, in some ways, a microcosm of how the book works as a whole—not as closed narrative, but as a solicitation to engage with this place, to begin to think it, its present and its past in the fulness of their difficult and unsettling complexity.

Andrew C. Wenaus is a writer, composer, and literary theorist. He is the author of The Literature of Exclusion: Dada, Data, and the Threshold of Electronic Literature (Lexington, 2021) and Jeff Noon’s Vurt (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). Recent creative pieces include Declaration of the Technical Word as Such (Sweat Drenched Press, 2023) and Ω – 1 Chronotopologic Workings (Schism Press, 2023). He is the editor of the experimental writing anthology Official Report on the Intransitionalist Chronotopologies of Kenji Siratori: Appendix 8.2.3 (Time Released Sound, 2023), and has two forthcoming collaborative works: a book of visual poetry with artist Rosaire Appel and a stage play with surrealist poet and novelist Andrew Joron. His critical writing has appeared in James Joyce Quarterly, Extrapolation, Science Fiction Studies, Paradoxa, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, Foundation, English Studies in Canada, Foundation, The Journal of Popular Music Studies, Big Other, and Electronic Book Review.He teaches at the University of Western Ontario.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

____________________________

[1] Virilio, Paul and Sylvère Lotringer. Pure War, Semiotext(e), 32.