Resonating with metaphysical awareness, humor, and clarity, Caryl Pagel’s Free Clean Fill Dirt is gracefully unglamorous in its foreboding, tactile verse that seeks to enumerate the material and moral decline of our planet. Pagel roots her eco-poetics in what she names “Ordinary Strata,” which service ekphrastic responses to familiar places that are in some form of disrepair. With a total of thirteen entries, these affective vignettes chronicle locations both wide (Cleveland, Lake Eerie, Chicago) and narrow (Palmer Square, Cottage Grove, Lamberton Road) in scope. In them, Pagel articulates a poetics of unease surrounding states of earthly disaster that disrupts viewing commonality as safe and emphasizes the falsehood of irreplaceability insofar as nothing is immune to its own ephemerality:

Vacant IHOP’s stripped sign more legible than it was with lights; Man remembering his childhood in Hough / Before the hospital buildings went up; Syphilis is Serious billboard / Abortion is Fake Feminism billboard / Hot Sauce Williams is closing / Wicked Taco is closing; In every living thing is stuff that is now lead / Plastics opioids pesticides estrogen.

Tones of sly hopelessness permeate Free Clean Fill Dirt and escalate as their scope gradually widens into piercing alarms of imminent eco-disaster. Specifically, by the final pages, Pagel juxtaposes a gentle admiration for a natural past, “Glaciers pressed the sandstone cliffs / They made all this,” with a cold injunction concerning its improbable future, “A child will be earth before their diapers are / […] A thousand plastic cars adrift.” This shift, from an observer of the ordinary to its arbiter, sees Pagel denouncing its innocuousness and defining its regularity as toxic, violent, and irreversible.

Perhaps most prominently arranged in “Lakeview Cemetery,” Pagel insists that modern existence has gone too far, too much damage has been done, and no apology or grievance will rectify its imbalance: “See versions / of this city as / it once was / over the version that / it is: abandoned / Walmart illuminated abandoned celestial / desolate country club abandoned.” And as the collection progresses further, it is clear that what is lost is more than a midwest city’s “past’s past’s making,” more than a version of a city and its country that is “Too too / far withdrawn to convey / that the conventional / means of making is / taking.” What is sacrificed is material justice and the equity of time, space, and living. That is, Cleveland’s industrious devolution is concurrent with its moral and ethical effacement, as is typified in Pagel’s recitation of Tamir Rice’s murder:

You / heard a boy one / day darted across / a park—darted you / heard into or / through the park—his / park—not far— / his park—a boy / waving with a / boy’s joy—what most / would say was /

a boy’s toy—playing / in a park / (his park)—near a / swing (his swings) / And who will carry /

his name now?

At the poem’s close, this stark allusion of ownership and recompense is interposed with an interrogative indictment of the discrimination inherent in how lost lives are chosen to be celebrated:

the gravekeeper’s window

reads: FREE CLEAN FILL

DIRTSee ROCKEFELLER’s Here, in its full context, Pagel’s titular clause transposes what is advertised into what is felt. A simple question of impartiality echoes through the frameworks of privilege, power, and priority of another violent American city. In “A History of the Color Orange,” Pagel again alludes to Tamir’s death as it pertains to her pseudo-Wittgensteinian account of the color orange that “has always / been a warning: / think of life jackets hunter’s vests highway / cones and even / the so-called safety tip of a toy / gun—a lump / of neon plastic supposed to distinguish what’s / “fun” from the / real thing but (fuck) the thing’s / tragic deal is that it can’t be undone.” Pagel’s exclamation is an ideological delineation of violence that signals its ineffable permanence and illuminates its indelible trauma: from “chemicals draining into / the gulf,” “airborne contagion,” “earth’s abysmal changes in an age / that likely contains / its own end” and, of course, “hell,” which is not figurative, “There’s proof: video of a twelve-year-old / boy being shot / in the park (it took just two / seconds—following zero / questions) by a so-called authorized adult.” What Pagel offers, then, are snapshots of surrounding and allusion crafted in the face of both brief and prolonged catastrophe where each iteration shares the same denotative irreversibility. Free Clean Fill Dirt does not offer escape but rather tempts us with ownership over our world that opts for “machine’s subtle lullabye as opposed to the / messy orchestral cacophony / of backyard crickets,” an utterance foretelling Pagel’s singular offering of refuge which she refrains, arms up: Just

let’s stare without purpose at the pattern

for a minute

Let’s stare without purpose at the pattern

for a minute

Let’s stare without purpose at the pattern

for a minute

Let’s stare without purpose at the pattern

for a minute

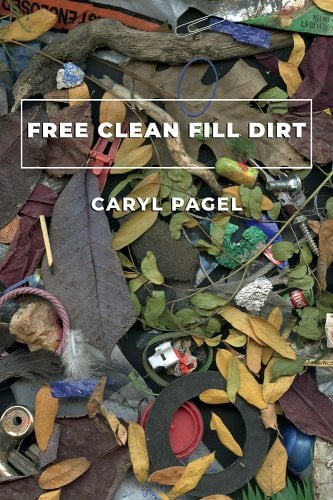

Free Clean Fill Dirt, by Caryl Pagel. Akron, Ohio: University of Akron Press, September 2022. 91 pages. $16.95, paper. Zachary Kinsella is a writer, musician, and coach. He lives with his spouse and three cats in Vermont. His writing has appeared in Full-Stop, Heavy Feather Review, and The Journal of Modern Literature. Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

buried hereWhere’s TAMIR?