We teach people how to treat us.

I don’t remember exactly where I first heard this little nugget of pop psychological wisdom, but it’s remained one of my most contemplated, and shared pieces of advice ever since. It sounds so simple, but for many people, myself included, it’s a truism that bears regular reminding. Though it makes sense, in a perfect world, to raise children to be hardworking, selfless, and altruistic, the extremely imperfect world we live in all too often turns these qualities against people, tapping their good faith efforts like a natural resource until their wells inevitably run dry.

The self-preservative realizations that trying too hard to make people like you is not attractive, that wanting too much to fit in is a surefire way to stick out, and that caring too much what others think of you can be downright dangerous, are ones that most people come to sooner or later as they navigate the pitfalls of professional and interpersonal life. But what about those people who don’t? The ones who never really learn to protect themselves? Who stay stuck in people-pleaser mode until they gnarl into contortions of resentment—walking open wounds of bitterness and regret—forever waiting around for some crumb of recognition—some cosmic justice—some exterior force to finally see them, acknowledge their efforts, and judge them righteous and good? We all know these people. We work with them every day. We see how hard they try. But what happens when they finally reach their limits? When their goodwill quietly curdles into ill? Are sociopaths born, or are they bred, little by little, one indignity at a time?

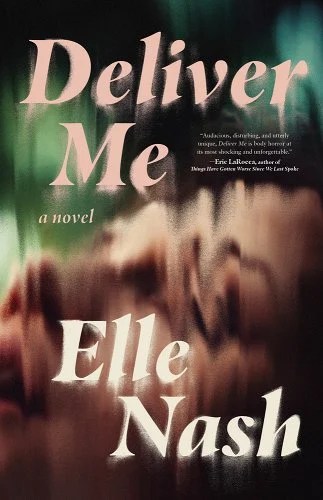

Enter Daisy, the first-person protagonist of Elle Nash’s powerhouse new novel Deliver Me, brimming with all the dark interiority of Joyce Carol Oates’ most damaged antiheroines. Warped by a fundamentalist religious upbringing, and now mortgaging her adult health and happiness in service to a brutal job at a chicken plant and an emotionally abusive partner, her circumstances are about as desperate as it gets—the razor-thin line between pinky-clinging to the bottom rung of late-stage capitalism, and falling clear off. She is a heartbreaking, and a terrifying creation—one who evokes pity and repulsion in near equal measure—and she is desperate. Desperate to overcome her scraping-by lot. Desperate to please everyone. Desperate to be a good wife, a good woman, a good person, but above all—and by a wide margin—desperate to be a mother.

Though she’s routinely dismissed as unserious or dim by those around her, Nash imbues Daisy with a complex, and complexly tormented inner life; a fierce tenacity with regards to her own gifts and desires, a tragically perceptive understanding of how differently the world sees her, and an array of manipulative coping mechanisms born out of both. Despite her flaws, she remains, at times, so self-aware as to almost beggar belief—how could someone with this much emotional intelligence allow herself to be treated this way?—but it’s this impossible dichotomy that makes her such a stunning, crosshatched portrait of the knots women tie themselves in trying to be all things to all people, and Gods.

Much of Deliver Me’s formidable power is derived from the, at times, almost unbearable tension created by these competing stressors, and I don’t want to tip too many of Nash’s painstaking narrative dominos, but for those who wish to go in completely blind, be forewarned that one, relatively early-on spoiler is forthcoming, if only because the book would be impossible to talk about further without it.

Now when I say that Daisy is desperate to be a mother, I mean that she’s positively consumed by it. It’s all she thinks about. Her every waking calculus is made in service to that … goal isn’t even the right word. It’s a physical demand. A spiritual need. The only thing that truly matters. And so, after putting all her remaining hope behind a couple of positive pee sticks, only to suffer her 6th miscarriage in devastatingly short order, she decides to just … keep going. To maintain the illusion. To manifest her dream. The clinical term is pseudocyesis, but America’s medical system is designed to fail people like Daisy. She’s already lived her whole life undiagnosed. In practice, it just means faking doctor’s appointments, stealing ultrasound photos, and stuffing herself to bursting with dairy products and fried fats (providing a fascinating, disgusting counterpoint to Nash’s previous eating disorder novel Gag Reflex) until she convinces herself, and everyone around her, that she’s still pregnant.

We get this information about a quarter of the way in, and the rest of the book is devoted to the aforementioned suspense wrought by Daisy’s ever-tightening web of deception. Through flashbacks to Faithful Floods, the backwoods Pentecostal outpost where she grew up, we see the lessons that forged her present-day understanding of her feminine duties (purity until you’re married, obedience once you are, and the twisted eroticization of both along the way). (Nash also includes a healthy dollop of prosperity gospel, highlighting how that particular strain of religious hucksterism preys mercilessly on the poor, subverting their Christian charity to line church pockets.) In Daisy’s relationship with David (whom she creepily, devotedly refers to as “Daddy”), we see a direct correlation between institutional evangelical sexism, and the learned inferiority that leads women to accept, and even cling to abusive relationships in adulthood.

David, a weak, lazy petty criminal, is an unsettlingly recognizable breed of asshole. Though he never hits her, their relationship portrays a routine, lived-in sadomasochism that never quite takes the threat off the table. And getting hit isn’t what Daisy worries about anyway, instead beholden to perpetual self-doubt and fears of abandonment. “Men [have] expiration dates attached to their patience for women,” she believes. “Any mistake can end the whole thing.” Indeed, David’s treatment of her resides so permanently between callous indifference and overt cruelty that she often daydreams of sharing physical violence with him, if only as evidence that he feels anything for her strongly enough to inflict it; as a potential test for her to pass; a path to earning his love once and for all. I won’t reveal his specific kink here—y’all have fun finding that one out on your own—but that Daisy considers it both her personal cross to bear, and the thing that “makes [her] better than an ordinary person” is helpmeet martyrdom 101.

Alas, no matter how hard she tries, Daisy faces rejection at every turn. She can’t ever be good enough. Not for the church. Not for Daddy. Not for her withholding mother or her childhood frenemy Sloane (there’s just not enough time to get into all the things this book does brilliantly well, but Nash’s depiction of Daisy’s and Sloane’s toxic bond is yet another). Even after she dons a prosthetic belly, carrying her pregnancy ruse almost all the way to term, Daisy rarely experiences the ambient kindness society traditionally visits upon women “great with child”—women with names like Sloane, or Payton, or Meegan—women with husbands and birth plans—who eat all the right foods and take all the right classes and buy their baby books new on Amazon rather than hoarding them secondhand from Goodwill. Despite having everyone fooled, it still feels like no one quite believes her, and as Nash slowly draws Daisy’s myriad delusions and conflicting lies taut around her, like twine cinching around a cut of fresh meat at her factory, it becomes clear that she’s nothing like these women, and never will be. Awash in their prenatal glow, all she can do is sweat through another day. Hoping she isn’t found out. Praying for a miracle.

I spent this entire book in that miserable in-between space of needing to cry, but not quite being able to get there, or thinking I might throw up, only for nausea to stick quivering in my throat. Though not based on a true story (at least not that I know of), it often feels like it could be, and its unflinching, vérité style made me uncomfortable in the same way I sometimes feel during nightmarish true crime documentaries—that wholly unmanageable helplessness born out of watching lives destroyed by the desperation of their circumstances. Anybody who follows my reviews knows I can hang with the horror crowd, but stories like this one get to me more than any cannibal holocaust or chainsaw massacre ever could. There is something about seeing humanity’s deepest ideals—religious faith, hope for a brighter future, unconditional love—corrupted, and then seeing that corruption subsequently crush those ideals’ most ardent adherents, that sends me to a place beyond horror, and much closer to despair. We teach people how to treat us, sure, but what often gets lost in that sentiment is that people also teach us how to treat ourselves.

It can be an absolutely vicious cycle—the endless giving and taking of advantage. Always putting others first inherently necessitates always putting yourself last, and Daisy accepts this born loserdom until she can accept it no longer. What remains is a nuanced collage of distinctly female anxieties—from puritanical sex shame to the modern self-esteem crisis to the baby-industrial complex—blooming into full-on psychosis. She is, quite simply, one of the most well-realized, and most important characters I’ve come across in years. The kind I will continue to think about, and worry about, and wonder about for many more years to come. As is so often the case with this kind of profoundly vulnerable personality, we simultaneously want to hold them tight—give them all the love they so desperately need—and push them away, for fear of that raw need infecting our own guarded hearts. In the end, I think I found her sympathetic longer than I was maybe even supposed to. She may actually be a sociopath. But if she is, the world helped her get there. She wanted, desperately, more than anything, and entirely too much, to be good.

Deliver Me, by Elle Nash. Los Angeles, California: Unnamed Press, October 2023. $28.00, hardcover.

Dave Fitzgerald is a writer living and working in Athens, Georgia. He contributes sporadic film criticism to DailyGrindhouse.com and Cinedump.com, and his first novel, Troll, was published in May 2023 by Whiskey Tit Books. He tweets @DFitzgerraldo.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.