Too often poetry is synonymous with the mind rather than the body, but, as Emily Dickinson reminds us, poetry should make “[our] whole body so cold no fire can ever warm [us].” Instead of forgetting the world and our bodies beyond the page, Ashley Howell Bunn’s somatic writing encourages us to use our breath, our whole bodies to feel more connected to the moment, to the words, and to the feelings evoked. Bunn’s in coming light invites us to access the stories we all hold inside our bodies, not merely in our memories.

With the body as a site of injury and healing, Bunn’s poetry takes us through loss and grief and moments of gratitude. The collection starts with a poem titled “vision” when that vision is sound, focusing on the music that make up our words. The poem begins with the vowels and consonance that build the poet’s name, including “shh” and “ash” implying something flamed out, silenced and burned to nothing. The poet’s name feels both like a flashback and a frozen present; we see the inevitable, a father’s death, written on a hospital wall. Through breath and sound the word hospital becomes “hos spit al spit / hos pit all” so the hospital becomes a pit, a dark trap to fall into. Hospital becomes spit, either to clear a throat or show distaste. But hospital is also reminiscent of “hospice,” sit,” and “respite,” a place to gather oneself and remember. Bunn deliberately creates dual meanings through sound, and the speaker finds consolation, relief in words that “hold” the silence and the beginning that comes from an ending.

Even poets struggle with how to begin when grief seems too overwhelming, whether writing an elegy or an obituary. When engulfed in grief and unable to remember “the transition of body to static,” or “what heartbeat symbolizes.” Throughout her poems, Bunn wisely shows us how to begin by inserting text boxes rather than traditional lines. In her poem “starting with a smaller space,” Bunn instructs us to let our grief “be held by / something else / less terrifying to write / a few small words into / the parameters of : then you can move it.” The text boxes allow separation, visually encourages us to take “a moment” and to “rest.”

Yet, text boxes don’t just supply a place for grief. In the poem “sight/yes he always sees me but/that’s only because/some sick mirror,” Bunn ingeniously uses text boxes to show the inability to reconcile two disparate ideas. The speaker fails to resolve two conflicting memories of her father: one, he holds her close; and two, he is passed out on the couch. How can you unite these two images, especially when that father is dying? Bunn literally takes the familiar advice about putting her grief in a box. Once on the page inside boxes, these two fathers don’t touch each other or the surrounding poem, although they can’t help but influence it. Through distance, we grow closer to reconciliation.

In the same way some things need to be boxed up, some things explode out. Oftentimes, the other side of grief is an appreciation for everyday moments. In the poem “root of rise (bread in the air),” the speaker expresses gratefulness for the large and small, even for seemingly everyday mundaneness such as dirty dishes, simply owning a sink, food enough for leftovers, even thin walls easily damaged by a fist. That hole becomes a family experience, dropping a son’s shoes to be lost in the house’s infrastructure. The speaker even expresses gratitude for “fungus enough in the air to make the dough rise.” Bunn passionately enacts this joy with poetic experimentation, lines and words that run together with thankfulness until we can’t help but feel it in our bodies too.

Through experimentation in form, Bunn intimately and courageously shares her grief at the loss of her father as well as her delight in being alive and in celebrating the body; the text boxes give the poet permission to use fragments, to stop mid-sentence, to focus on how the body feels, to offer no easy answers, to provide no consolation. But do we really need to be given these answers? When the speaker writes, “being a body is harder than expected” we don’t need more information because we already understand. Bunn’s in coming light encourages us to rethink the way we see the world because we can see with more than our eyes; we should learn to “notice stillness” and pay attention to movement and its absence throughout the body, to feel it—to feel everything—through each limb, each bone, and in the skin.

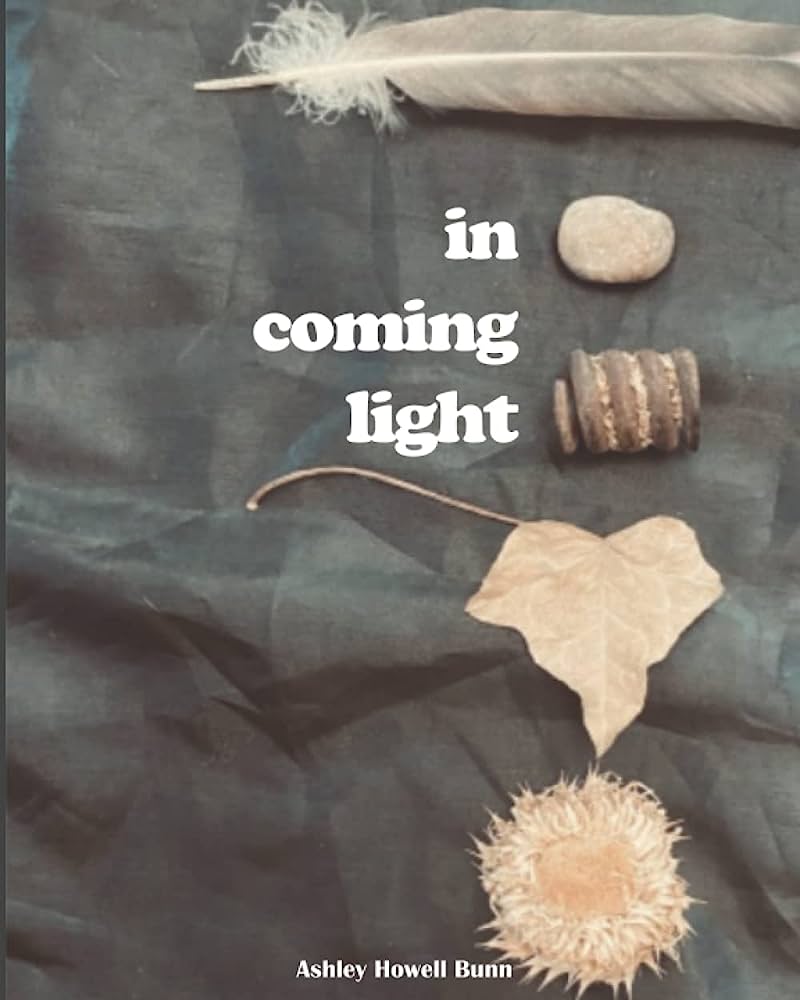

in coming light, by Ashley Howell Bunn. Middle Creek Publishing. 55 pages. $18.00, paper.

Kara Dorris is the author of two poetry collections: Have Ruin, Will Travel (Finishing Line Press, 2019) and When the Body Is a Guardrail (2020). She has also published five chapbooks: Elective Affinities (dancing girl press, 2011), Night Ride Home (Finishing Line Press, 2012), Sonnets from Vada’s Beauty Parlor & Chainsaw Repair (dancing girl press, 2018), Untitled Film Still Museum (CW Books, 2019), and Carnival Bound [or, please unwrap me] (The Cupboard Pamphlet, 2020). Her poetry has appeared in Prairie Schooner, DIAGRAM, I-70 Review, Southword, RHINO, Rising Phoenix, Harpur Palate, Cutbank, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Tinderbox, Puerto del Sol, The Tulane Review, and Crazyhorse, among others literary journals, as well as the anthology Beauty is a Verb (Cinco Puntos Press, 2011). Her prose has appeared in Wordgathering, Breath and Shadow, Waxwing, and the anthology The Right Way to be Crippled and Naked (Cinco Puntos Press, 2016). A poetry anthology she edited, Writing the Self-Elegy: The Past Is Not Disappearing Ink, is forthcoming from SIU Press in 2023. She earned a MFA in creative writing at New Mexico State University and a PhD in literature and poetry at the University of North Texas. Currently, she is an assistant professor of English at Illinois College. For more information, please visit karadorris.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.