Pathetic Literature, an anthology edited by Eileen Myles, is a wide-ranging collection of writers and poets, both in the US and abroad. It offers us an intricate mosaic, where each story resonates with the other, developing themes and ideas in a subtle way. I can only hint at some of the major themes in this brief review/essay. While reading the anthology, I kept thinking of the quote by the collage artist, Jess, and I thought it could serve as a good description of the driving force of many of the poets and writers in this anthology: “It was the variety of existentialism that emphasized alienation, and risk, with its alternate possibilities of despair or total experience, either of which might end as total insanity, but either preferable to the rationalistic traditions which had produced such insanities of its own as wars, prejudice and little houses of death in suburbia.” Or Dodie Bellamy describing herself as “a post-punk Milton waging a one-woman war against structure, taste, logic and even words themselves.” Or when Raymond Foye asked John Wieners, “Do you have a theory of poetics,” and Wieners responds, “I try to write the most embarrassing thing I can think of.” Or when Audre Lorde writes, in Poetry Is Not a Luxury, Sister Outsider; Essays & Speeches:

My response to racism is anger. I have lived with that anger, ignoring it, feeding upon it, learning to use it before it laid my visions to waste, for most of my life. Once I did it in silence, afraid of the weight. My fear of anger taught me nothing … Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against those oppressions, personal institutional, which brought that anger into being. Focused with precision it can become a powerful source of energy serving progress change. And when I speak of change, I do not mean a simple switch of positions or temporary lessening of tensions, nor the ability to smile or feel good. I am speaking of a basic and radical alteration in those assumptions underlining our lives.

Or Paul B. Preciado who writes, in An Apartment on Uranus, “We could say, reading Weber with Butler, that masculinity is to society what the State is to the nation: the holder and legitimate user of violence. This violence is expressed socially in the form of domination, economically in the form of privilege, sexually in the form of aggression and rape.” Or when Kafka in the letter to his father (included in the anthology) refuses the bourgeois ideal of marriage that defines his father’s world:

But we being what we are, marrying is barred to me because it is your own domain. Sometimes I imagine the map of the world spread out and you stretched diagonally across it. And I feel as if I could consider living in only those regions that either are not covered by you or are not within your reach. And in keeping with the conception I have of your magnitude, these are not many and not very comporting regions – and marriage is not among them.

These are the kinds of ideas that came to mind while reading. This is the kind of “literature” written by those who reject the strictures of language or lifestyle in their attempt to expand their vision of the world and themselves, whether through experimentation with drugs, sexual practices, exploration of hermetic knowledge, or even through breaking down the grammatical structures of language, i.e., in order to use language as a political act. It’s about expanding your senses. In the story “Worms Make Heaven,” Laurie Weeks writes, “On YouTube I learned that the ancient Egyptians were so finely tuned they had 360 senses defined, as opposed to five.” This anthology calls on us to expand our idea of what literature is, to open our minds to alternative visions of the future. For those who don’t care about literature, all of this is just pathetic i.e., miserably inadequate and of very low standard or that which tends to arouse pity, especially through vulnerability or sadness. Pathetic Literature is all about our vulnerabilities, our sadness, our pain, our anger, our desires. In other words, it celebrates real life.

Of course, the normal order of things is maintained by erasure, destruction, induced lack of memory, detention, punishment; the visible, as the State, is given priority over the invisible, the migrant, the homosexual, the lesbian, and asserts its dominance by the use of violence; and it’s violence against women, against children, against non-white men and women, against animals, against the planet as a whole i.e., against those whose gestures and appearance are not socially accepted and considered inferior. Andrea Dworkin, in “Afterword,” quotes Judith Malina:

Through the social structure begins by framing the noblest laws and the loftiest ordinances that ‘the great of the earth’ have devised, in the end it comes to this: breach that lofty law and they take you to a prison cell and shut your human body off from human warmth. Ultimately the law is enforced by the unfeeling guard punching his fellow man in the belly.

Remember that the Nazis destroyed modern art in order to produce images that conformed to their ideology; paintings of bucolic scenes, with healthy and strong heterosexual women and men maintained their idea of the all-powerful state apparatus while the others were being tortured and killed in concentration camps (see Jack Halberstam’s brilliantly satirical essay in the anthology on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s overblown, sexist, and ridiculous 6 volume book, entitled My Struggle, which is the same title as Hitler’s Mein Kampf). Instead of viewing the world as unified, singular, and bounded by walls it is more imaginative and revolutionary to view it as multiple, borderless, stateless, and changeable because the territory is not the map. So, as Precious Okoyomon writes: “Fleshy animal // nothing is pure, invert yourself.” The anthology explores alternative feelings, those that arise when confronted with authority, or the “right” way to act or behave enforced by the white, heterosexual, god-fearing, males and their women. In other words, healthy and not sick.

Porochista Khakpour writes in her powerful book Sick, an excerpt of which is in the anthology, about her difficulty finding a proper diagnosis for what she is feeling. No doctor is sure about the right pills to give her, and so the illness becomes a kind of unknown about which the doctors can assert their control over her. In the political/legal/medical system as it is constituted, if one wants to live, one must adopt and accept its codes; the medical and legal systems cannot accept the unknown, what deviates from their conception of the truth; thus, the family exists, the law exists, the Book exists, psychiatry exists, even God exists. But the sick do not exist. It’s about freedom.

In “Potatoes or Rice?” Matthew Stadler writes: “My freedom is guaranteed by a silicon chip embedded in my residence permit. The biometric information stored there was taken from me by a large, egg-shaped machine in a pleasant suburban office in Hoofddorp, the Netherlands … nothing in my body can contravene the testimony of the chip: not my words, not my knowledge, not my soul, not my humanity. None of that counts; only the chip.” Perhaps the human is approaching the end, as technology envisions a world where man is no longer necessary. It sounds like science fiction, when researchers say that AI programs, when taught a language, can immediately learn another language on their own, with no human intervention. Man is being transformed in an irreversible way in this age of digital technology, when there are more cell phones on the planet than people. The very fact of their existence alters nature in a fundamental way: our dependence on the machine. We are slaves of the death cult of capitalism that sees us as sick, hopeless, suffering, poor and not worthy of saving.

Reading Pathetic Literature, I thought of the polarity Paul B. Preciado shows between the conceptions of the North and South as a good way to understand the many interconnecting themes in the anthology. In the present time, the far-right makes use of this invented geography and chronology, which is actually the result of colonialism, power, knowledge and space. The argument goes like this: “The South is primitive and past. The North is progress and future. The South is the result of a racial and sexual system of social classification, a binary epistemology that opposes high and low, mind and body, head and feet, rationality and emotion, theory and practice”; the South is poor, its inhabitants are lazy, ignorant, filthy, sexually obsessed; the south “is an animal, feminine, infantile, a fag.” On the other end of this spectrum, the argument goes like this: the North is “human, masculine, adult, heterosexual, white … healthier, stronger, more intelligent, cleaner. The North is the soul and the phallus. Sperm and currency. Machine and software. It’s the place of memory and profit. The North is the museum, the archive, the bank.” On the one hand, cleanness, intelligence, health, heterosexuality, the phallus, and on the other, the cesspool, the mine, the rubbish, the anus; but the South is also feared because it is the seat of revolutionary power. We must collapse these vertical distinctions which enforce a duality of inferior and superior, and hack the power grid; imaginatively interrupt and redirect the flow of knowledge, moving through fissures and gaps, to arrive at a new language, a new way of connecting to each other [see Times Square Red, Times Square Blue by Samuel R. Delany, and “The Slow Read Movement” by Sparrow; also see Pain Journal by Bob Flanagan, “An Obituary” by Joe Proulx, and “The Merry Widow and The Rubber Husband (or How I Caught HIV: Version 4; Fall 1983)” by Joe Westmoreland, as well as the writings of most of the poets and writers in the anthology] All the writers and poets in Pathetic Literature are in the above sense, “Southern.” Life is messy, complicated, often contradictory; the texts in this anthology celebrate these aspects of life. Many of the texts also reminded me of what I was reading and experiencing earlier in my life.

I remember going out to the Limelight in NYC and various other clubs, dancing all night and drinking, and wandering the New York city streets at dawn on my way home to Jersey. At the time I was getting an education in the alternative knowledge not taught in the Catholic schools I attended which opened new worlds and allowed me to escape the confines of the suburban neighborhood where I grew up. I often went to the Poetry Project, and was reading Alice Notley, Eileen Myles, Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, Genet, Ginsberg, Wieners as well as underground comics like the Freak Brothers or Robert Crumb’s Zap; I was going out almost every other night, riding in a friend’s small beat-up Honda with new wave and punk music playing on the car radio; we talked and laughed, on our way to the beach, or to a live concert, or a night club in New York. I remember long hours alone, in my parent’s house, being simply bored, with nothing to do; I couldn’t sleep. So, I read. I’d read for a while but then did nothing; maybe I talked on the phone a bit. But this sense of boredom, this sense of doing nothing, was not an oppressive feeling; I never felt, during this time, that I had to do something, that I had to be productive. This was before the Internet and cell phone deceived us all into thinking that every moment is precious and must be “saved:” there is now the illusion that something is always happening; that you may miss something: an email with urgent news, or some video on YouTube about the current political situation, or a friend’s “like” or comment on a Facebook post. Sparrow’s “Slow Reading Movement” reminded me of those quiet hours when I would slowly read various novels or books of poetry.

I remember the Tomkins Square Riots, the Aid’s scare, Koch’s flamboyant and often witty pontifications, the Crack epidemic, the Wall Street crash. I remember a gay friend’s suicide, violence in the streets, pickups in bars, talking all night on the phone; I remember waking up in a friend’s apartment many times with a splitting headache after a night out; all the sex, all the failed relationships. You had to experience the good with the bad, the black magic with the white. No use forcing the issue. Let it go. Tomorrow’s a new day. So, who is Pathetic Literature for? Everyone. It’s like a stiff drink, or a good joke to lift your spirits when you’re down. It’s like that good friend you can tell your secrets to at 3 a.m., after a night out. This brilliant anthology calls upon us to continue to dream of an alternate future, one where the immigrant or outsider is not demonized, where racism does not exist nor homophobia, or xenophobia, where men and woman, gay, straight, or trans have the right to exist in a free and democratic world.

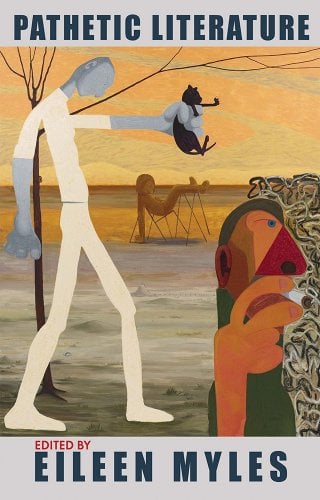

Pathetic Literature, edited by Eileen Myles. New York, New York: Grove Press, November 2022. 688 pages. $34.00, hardcover.

Peter Valente is a writer, translator, and filmmaker. He is the author of twelve full length books. His most recent books are a collection of essays on Werner Schroeter, A Credible Utopia (Punctum, 2022), and his translation of Nerval, The Illuminated (Wakefield, 2022). Forthcoming is his translation of Antonin Artaud, The True Story of Jesus-Christ (Infinity Land Press, 2022), a collection of essays on Artaud, Obliteration of the World: A Guide to the Occult Belief System of Antonin Artaud (Infinity Land Press, 2022), and his translation of Nicolas pages by Guillaume Dustan (Semiotext(e), 2023).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.