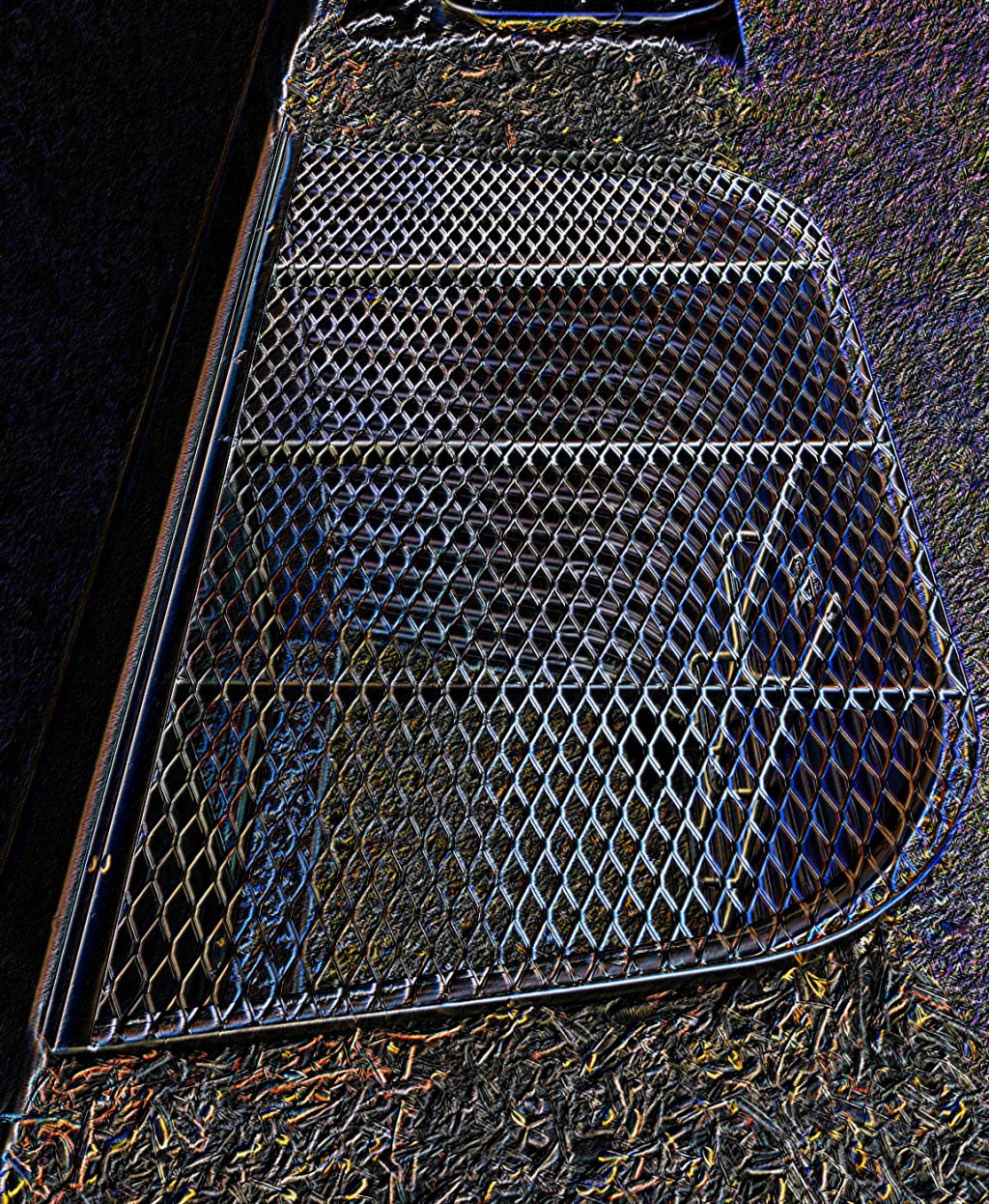

There’s a frog ribbitting super diligently outside the basement window. The window looks out into a chicken wire well. Sometimes, after a real wet spell, Maddy will invite us all over to gather at the window and peek out at whatever unlucky thing is stuck at the bottom of the hole. Mostly we see spiders and worms and other empty things. We don’t pay them much mind. Spiders and worms are kind of born dead. Maddy tells us this. She is convinced that some things are made bad on purpose, so that it’s easier to hurt them, get rid of them, squish them below the heel of a shoe. Throw ’em all away.

Sometimes bigger things get trapped in the window well. We saw a gecko once. We were surprised by what she looked like. We thought geckos looked like boogers, green with a luster like freshly-chilled jello. Instead, she was wrinkled and fleshy. We didn’t touch her, but we agreed that it looked like she might feel like running the tip of a finger over a brick. She hunkered down by the window for a day, but eventually got herself out by scrambling up the chicken wire.

A rabbit got stuck, too. She was little and speckled and breathed so fiercely we thought she might pass out. Could rabbits faint? We didn’t know. We liked watching her that first day. She quivered against the window and never looked at us full on, but out of the corner of her eye. Maddy said this was because she was afraid of us. We didn’t like that. We wanted to open the window and rub the thick fur of her feet, little flashes of white when she was itchy or moving around. A secret, tender spot. We wanted to show her we could be trusted. We knew of her softness. We would guard it with all we had. We wanted to free the rabbit after that, but this made Maddy angry. She liked to startle her by banging loudly on the glass. She liked to hear the dirt shift as she tried to hop up and free herself. Maddy stopped inviting us over to look at the bunny. She made us stop asking her to let it go. One of us got real upset and called Maddy’s parents. We still don’t know who it was. Nobody wants to ’fess up because Maddy can hurt better than all of us. Her dad went to check the well, and it was empty. Said it probably found a way to climb out. After Maddy was done icing us out for a week, we asked her what had happened to the rabbit. She refused to tell us. Everything about her is mine she said.

We’ve seen a frog or two in our time. They usually figure out how to get up and out. They’re always the small little lawn toads, the color of rot, the ones that piss everywhere the minute you put your hands on ’em. When we first hear him, Maddy gets up and peeks out and confirms—same thing, same quarter-sized toadlet, nothing really new.

“He looks like he would burst if I bit into him,” says Maddy. She’s always saying things like this. She loves biting, breaking, splitting things in two to see what makes ’em up. “He looks like a little laundry pod. Like he’s just liquid and skin and that’s all.”

We giggle at the idea and move on, chatter about school and about our great loves, our skinned knees and best bruises. Maddy doesn’t care for this and waves her hands to get our attention.

“Don’t you want to bite him too?” She points into us, cleaving us into ourselves. She looks at each of us for an answer.

We all answer back in our own way, sure and I mean I guess and I get it I think and so on. Maddy is unconvinced, or maybe unsettled with our lack of enthusiasm.

“OK, but would you. If I opened that window and brought him in here, would you do it?”

Maddy, with cerulean eyes under blunt black bangs, moves to the well window and we all slow wail, a groan that spirals wild as her fingers graze the plastic latch. She turns to face us. Her face is all red like she’s been crying.

“Fine,” she says, “fine. Forget it. Let’s play a game, OK?”

OK, we tell Maddy.

She gathers us into a circle around her beanbag chair. We press together; our shoulders dig into one another and assure us of our togetherness. Maddy’s parents are somewhere upstairs, but we can’t hear them. It’s dark out now. The basement lights are dim. The air is a little wet, still heavy from the early-day rain. In this moment, no one else exists as much as us.

Maddy waits to break the silence. We quake with one long shiver. We are still learning to recognize fear.

“Truth or Dare?” Maddy asks. “Truth! Truth,” we shout, careful not to let even a hint of dare hang in the air past her question mark. We bite our bottom lips. “I know who it was, just so you know. But I’m gonna let you ‘fess up in front of everyone.” She looks to each of us, her black hair wild, her face tear-streaked. “Well? Come on!”

Our eyes grow wide. We look at each other and all answer back in our own way, wasn’t me and no clue and maybe someone else did it. Maddy loses her patience.

“Alright fine! We’re going with dare then. Margot, you’re up!” she announces with an edge in her voice, her eyes locked on Margot, who shrinks like a slug doused in salt.

Margot wants to know if she has to do it while the toad is still alive. Maddy says matter-of-factly that the burst, the pulse of the gush, won’t be as good if we kill it first, and we look around the circle at each other without a word, lips pursed tightly. Margot emits a laser glare at Maddy and tries to turn the mood with a judgmental “eww, Maddy, that’s disgusting!” If she can get even one more of us to join in with vitriol, just one more of us to agree in this moment that Maddy, as a person, is revolting, there’s a chance Margot will get out of this. But watching our pupils widen and our shoulders pink with the pressure of one another’s weight, she knows it’s futile.

We look at each other and murmur—that would count—wouldn’t it? A dead toad is still a toad.

“Come on, Maddy. What if it pees on my tongue?” Or worse, we think, what if it shits out the slick beetle shell of a June bug or the iridescent wings of a fly?

Maddy wipes her nose on her sleeve, sniffs, and walks toward the window. She unlatches it, and the roar of locusts and the croaky buzz of fatter toads leak into the room, thickening the humid air. Maddy reaches into the well and fumbles with the toad, her hand smeared with piss as soon as she’s got a good grip.

Unblinking, Maddy holds the toad up close to her face to inspect it, and our pulses synchronize with her movements. “A bigger toad would take a few rounds of Black Cats up its ass and m16s down its throat before it’s really toast,” she says coldly. Our eyes grow wider, our lips purse with pang. We wonder if Margot’s really the one who called Maddy’s parents about the rabbit when she retreats to the far corner of the room to put some distance between herself and Maddy. There’s a saddle draped over a barrel in the corner, and Margot nervously fingers the latigo. The rest of us press our shoulders into each other until we’re sick with ache.

Then we break apart, our shoulders throbbing. Some of us inch toward the doorway. Others shuffle toward the window to get a closer look at the juicy toad. No one gets too close to Margot. We’re all eyeing our escape routes, considering the possible exchange of clemency for allegiance.

“Besides, won’t be worth it if it’s blown to smithereens. Maybe a BB or two right between the eyes,” Maddy suggests, lowering the toad and looking now in Margot’s direction.

Maddy strides across the room to a closet with a beaded curtain where the door should be. She digs around and pulls out a gun with her right hand, the toad still in her left. She props the gun against the door jamb, then goes back in for a mostly empty box of Daisy BBs. She holds them out to us like sandwiches and Sprite—here friends! We’ve got options!

“But holding its head underwater in the bathtub—that’d probably be easiest,” Maddy says. We know a drowning would spare its jello-taught belly too. She tosses the box of BBs on the bed next to a green plastic alien wearing oversized sunglasses and walks slowly toward Margot holding the frog firmly in both hands against her chest like a wind-up music box with a porcelain ballerina inside.

“How about another truth?” whimpers Margot, clearing her throat, glancing at the saddle, at us, refusing to look at Maddy full on.

“I don’t have any more questions—”

We gasp and let the first beginnings of swoon and whine escape our throats.

“Now bite the fucking frog, Margot!” Maddy yells.

Margot’s face drains of color like a waterlogged lily when Maddy thrusts the toad inside Margot’s open mouth and clamps her hand down hard across her lips and chin. Margot stumbles backward with Maddy’s momentum and falls to the floor clutching her throat in a silenced shriek—Maddy’s hand is still tight on Margot’s mouth when she feels the warm gush of animal on her palm. Margot’s struggle beneath her, bucking legs and voiceless screams, begins to die down when Maddy fixates on a slow stream of purple liquid creeping out from beneath her forefinger and down Margot’s chin.

We’ve each clapped a left hand across our own mouths, muting our mutiny. The most we can conjure in our own way is Maddy stop and get off her and don’t. But we keep our eyes on the exit, a foot pointed toward the door.

Maddy shifts her gaze upward from the gooey mess, her claw still clamped across her friend’s mouth. Then Maddy notices that Margot’s eyes look exactly like the rabbit’s in the moment just before its death.

Abby Feden (she/her) is a fiction writer living in Stillwater, Oklahoma. She is the winner of The 2020 SmokeLong Quarterly Award for Flash Fiction. Her work appears or is forthcoming in SmokeLong Quarterly, X-R-A-Y, Third Coast, Superstition Review, Best Small Fictions 2021, and elsewhere. Feden received her MFA from Western Washington University and is pursuing a PhD in Creative Writing at Oklahoma State University.

Allie Spikes (she/her) is a writer living on the Puget Sound. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Pinch, Gulf Coast, The Los Angeles Review, River Teeth, Sugar House Review, Bellingham Review, and elsewhere. Her nonfiction has been listed as Notable in Best American Essays 2022, and her poetry collection was a finalist for BOA’s A. Poulin Jr. Prize 2022.

Image: utahwindowwellcovers.com

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.