Let our meditation on Joe Hall’s terrific new collection of poetry, Fugue and Strike, begin with a brief survey of fecal refuse in nature poetry. Here’s Tommy Pico:

Crappy water

Shoots thru purgatory creek

On its way to the Colorado River

And here’s Trevino L. Brings Plenty, resplendent:

You mean, if you see this world In short, this shit’s everywhere, as Brandon Shimoda confirms: Two deer Shit Or there’s G.E. Patterson, sliding among idioms of “shit” (“You got trees all dappled with sunlight and shit”), Lucia Perillo (“the best birding is done in foul-smelling places,” she writes in “Bulletin from Somewhere Up the Creek,” and we know which creek she’s up), D.A. Powell (“dutifully, artfully / enriched with sewer sludge”), Anthony Seidman (“a sewage-tide of shadow”), Laura Gray-Street (“And not only stormwater but also / untreated human and industrial waste”), Arthur Sze (“a kid repeatedly kicks a dog near where / raw sewage gurgles onto sand”), Chase Twitchell (“haunt the air above the sewer grate”), Juliana Spahr (“we let the runoff from agriculture, surface mines, forestry, home / wastewater treatment systems, construction sites, urban yards, and roadways into our hearts”). The anthology goes on. It’s almost as though, as soon as we mention water, we’re moved to recall the shit. It’s a gesture of responsive juxtaposition, an ethics of recollection. Perhaps, this reflexive muddying shows the environmentalism of a particular era, as in this exchange from 1999’s She’s All That: ZACK: Check out that water.

LAYNEY: You know how many gallons of chemicals are dumped in the ocean each year?

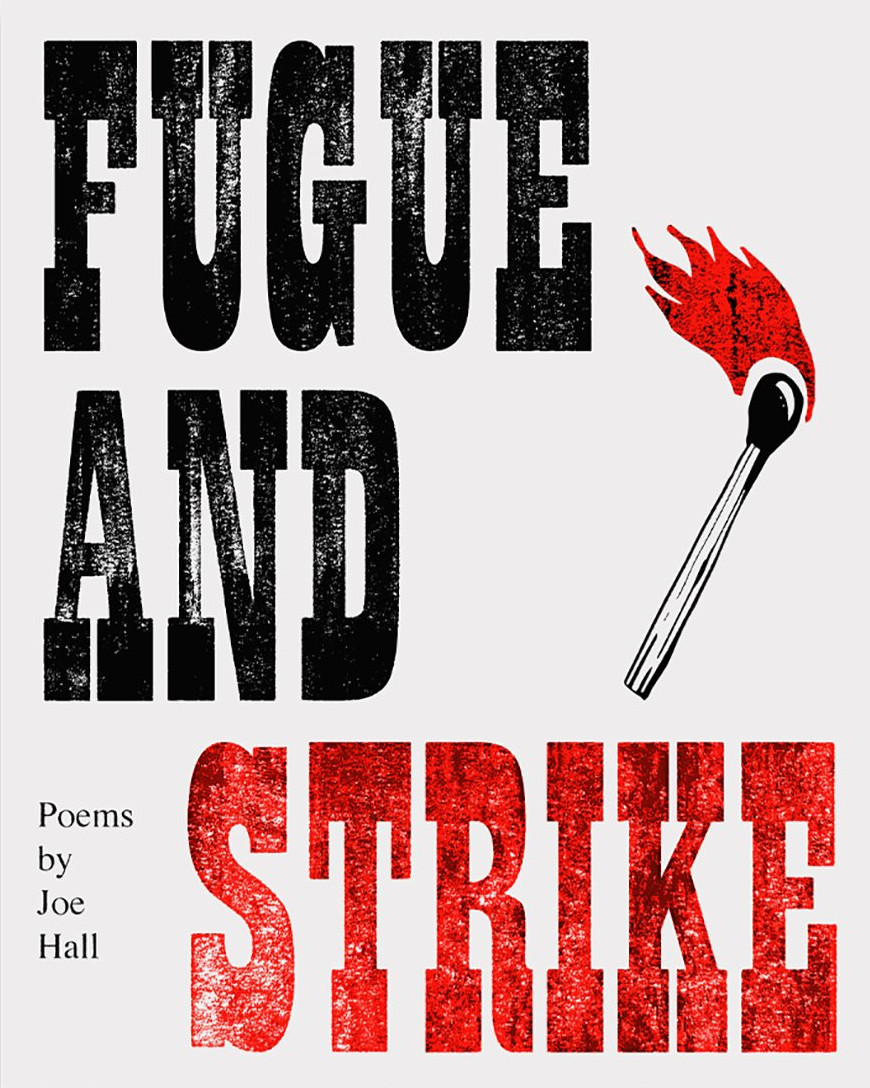

Or else it’s a continual tradition, old as spring. “As we, the Great One among all creatures, shall go about contemplating our self-prohibited desires as we promenade before the inward review of our bowels … it is spring by Stinking River,” William Carlos Williams wrote a hundred years ago. In considering the poetics of shitty rivers, one might wonder what other modes are available. How might we move beyond momentary juxtaposition (“there’s the water, there’s the shit”)? That one-two punch might risk leaving the scene inert; we see the mannered glance, in passing, and feel an eco-political tinge, but what else does it activate? It’s scenery. “I know what we call it / Most of the time,” wrote James Wright of a “beautiful” river. That shows one approach: Wright doesn’t focus on staging the association; he assumes we already share it. The water and the shit are inseparable, and we know it. That is, Wright’s view isn’t of the shitty river. It’s of what we make of the shitty river. There’s a related approach in Juliana Spahr & David Buuck’s collaborative text An Army of Lovers, with its focus on systems and myth and necropastoral between-spaces. “All he had wanted to do was write nothing about an unremarkable place,” the authors write of one character’s poetic desire, “write a picturesque story of a post-pastoral plot of land.” But a flood of sewage and cultural “shit” spews onto the scene. Our heroes, Demented Panda and Koki, burn it back, but “the raw sewage remained. With nothing to hold them, Demented Panda and Koki sat there in the raw sewage. All that was left was the feeling of sitting in raw sewage and knowing lostness deep inside.” Is this the common era? The raw sewage, which remains, and the lostness, and the standing by? * Enter Joe Hall’s Fugue and Strike, his fifth collection, and its careening 43-page sequence “Garbage Strike,” a mixed-form investigation drawn from archival research into and around labor, revolt, and waste. The shit gets real; rather than being a marker of a damaged landscape, refuse is the landscape itself, a plot people are forced to work. It looks back at us, meeting “the eyes crossing boundaries / to become its own life blooming / shit exuberant.” This exuberance frames a global vision, across centuries, which connects the Dirty Protest of imprisoned members of the Irish National Liberation Army (“prisoners refusing to leave their cells to wash or use toilets”) to “The Garbage War” in Tokyo Bay in the early 1970s to sanitation workers advocating for PPE in Pittsburgh in 2020. As in Hall’s 2018 collection Someone’s Utopia, which combines documentary preservation with attention to the “amnesias” that can result from work and its conditions, the sequence moves between choreography and cacophony. It sheds precise, essayistic light. It also highlights what might get shed (outrage, startling connections, insistent fragments) by a less capacious mode. Among its capacities, “Garbage Strike” makes slick use of the registers of “shit.” The word becomes close to a unifying, globalizing drone. It stands in for what’s closely of the body, what the body might leave behind, and what we’re forced to carry: “City residents could ignore protestors but not their own piling shit”; “Hired to take a bunch of shit from her acerbic boss”; “If we can’t / separate ourselves from shit.” To be clear, Hall’s diction and references are wide-ranging; there’s the frequent clang of shit hitting the fan, but it’s among many other currents. Still, one might note the repositioning of the term at key moments, as in this passage, which concludes a section about what Hall characterizes as the destructively lapsarian views in Thomas Burnet’s Sacred Theory of the Earth: If the whole world was a ruin, the dump could be anywhere, upon any other.

Romantic conservation, what would become in the United States settler conservation at its worst—denying the naturalness of open, changing systems, denying, also, the right and history of indigenous peoples in using and producing their landscape, folding them back into nature—produces aliens and invasive species while disappearing first peoples to get back to the egg, the Eden, a healthy colony for the colonist.

Edward Abbey was a piece of shit.

The world is not a ruin.

The general term becomes specific epithet, cast back onto Abbey, which might highlight the “colon” in “colony.” The world, Hall asserts, isn’t a dumping ground, in a fallen state; it remains unruined, despite its devastations and waste. Is there a more renegade spiritual vision, to deny the fall, to insist that this world, despite its massacres and microplastics, is an Eden? What’s radical, I suppose, is how that at once indicts paradise—this is paradise?—and lives in it. If we haven’t been cast from the garden, we remain responsible for it. “There is one kind of knowledge—infinitely precious, time-resistant more than monuments, here to be passed between the generations in any way it may be: never to be used,” Muriel Rukeyser wrote of poetry, as a natural resource, in The Life of Poetry. Hall suggests that seeing land and labor similarly—as precious, as not for extractive use—may be one way to strike back against the utilizations of segregation, inequitable working conditions, environmental degradation, dissent manufactured among workers, and so on. (In the historical garbage strikes he researched, Hall notes, struggles based in class, race, and imperialism variously intertwined and conflicted: “In the case of the Dutch carters [of waste], their strike had a terrible outcome: a cross-class compromise to exclude Black workers from that labor market, contributing to their treatment as super-exploitable workers.”) Writing is also implicated: “At least one historian of ink says the first writing tool must surely have been carbon. Carbon was certainly preceded by piss and shit,” he tells us. Perhaps, Hall is writing his way into relation with a literacy that’s closer to shit than to carbon, one in which the body (and the body politic) strives to be text and author of its own worlds. Late in the collection, a poem reports finding a seedling in the tub drain. Hall surmises that it’s a flax seed that, having passed through him whole, took root among “a tablet of my partner’s hair and coconut oil shampoo.” From the wastes of our bodies, here is life of growth and holding on. * “Garbage Strike” is a vital addition to poetries that merge documentary modes with lyricism that doesn’t reconcile into easy theses. Add it to the shelf with A.R. Ammon’s Garbage, and Pico’s Junk, and more localized observations of waste such as Brenda Coultas’s A Handmade Museum. It represents the “strike” in the book’s title, among shorter sections of the book, such as “People Finder Buffalo,” which is a chilling response to the many deaths recorded in the Erie County Jail under the administration of Sheriff Tim Howard. The “fugue” of the title is represented chiefly by “Fugue and Fugue,” fifty pages from, the book suggests, a longer sequence. In music, a fugue picks up phrases and adds to them; the repetition of “fugue and fugue” brings to mind addition that also cancels itself out, or stays anchored, denying overt variation in favor of accretion. The final poem in the sequence, which labels itself a “process note,” suggests one way to think about this sequence’s “language for exhaustion”; importantly, the preposition “for” distinguishes Hall’s phrase, and framework, from the familiar postmodern notion of the “literature of exhaustion”: what can I write when I feel like each phrase is a soft shell The poet begins, as often happens, with the feeling that language needs to do more, not in order to create or surpass the world as it’s been given, but to match the blasts that are already blowing us apart. The scene is tender, rich with communion among friends that reaches beyond communication. That underlying sense of what we owe each other, because of what we’re already a part of, among all that might discard us, runs through Fugue and Strike. It makes it an important volume for our moment of ecological catastrophe, which makes waste of both specific memory—the history of labor, the tactics we’ve had for survival—and the “knot of wrinkles” we can feel ourselves lost among. Fugue and Strike, by Joe Hall. Boston, Massachusetts: Black Ocean. 126 pages. $17.00, paper. Zach Savich’s latest book of poetry is Daybed (Black Ocean, 2018). He teaches at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

through black-light vision,

knowing everything covered in shit, this planet

would be a beautiful glow

In the River

One deer licking the other

Deer’s ear

Everywhere

against the blast of a horn an angel blows to end the world

and there was R wearing a shift that said IRAN, IRAN,

IRAN, IRAN while M reads his piece on Ronnie Spector

and J had us draw the lodger in our head, mine was a

knot of wrinkles telling me to burn this before

reading, there were things I was afraid to say

to these long friends