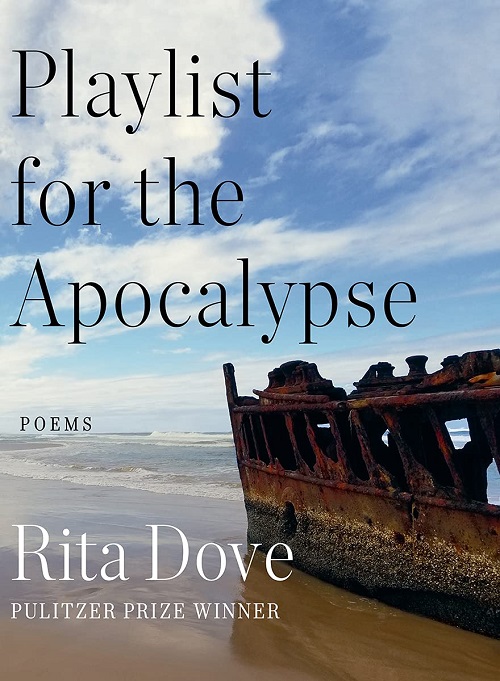

Playlist for the Apocalypse is Rita Dove’s first book of new poems since 2009’s virtuoso Sonata Mulattica (her Collected Poems: 1974–2004, also from W. W. Norton & Company, appeared in 2016), and well worth the twelve-year wait. Expansive in theme, tone, and subject matter across its six sections, Playlist for the Apocalypse defies generalization and offers ample opportunity to appreciate Dove’s extraordinary, honed talents, especially her gift for bridging past and present through persona, her musical phrasing, and her deft handling of form. Like the best playlists, this assured collection both satisfies and surprises.

A found sonnet drawn from wig advertisements, a two-column mirror poem, and a Golden Shovel: these and other forms lend a mosaic-like quality to “Time’s Arrow,” the book’s first section. In poems which consider the intersections of family, race, history, and memory, Dove’s sparkling, jewel-like images range from playful (a passenger waiting for a flight’s boarding call is “perched like a seal trained for the plunge”) to luscious (in “Girls on the Town, 1946” the subject and her friends “have lacquered up and pinned on your tailfeathers, / fit to sally forth and trample each plopped heart / quivering at the tips of your patent leather / Mary Janes”) to knowing (a man is “one righteous integer of cool cruising down a great-lipped / channel of adoration”).

But even in comparatively less adorned poems, like “Eurydice, Turning,” Dove knows just how to hold our attention, in this case with reversals and digressions that mimic the whiplash of the poet-speaker’s experience of her mother’s memory loss. A “good day” topples with the dread of a simple phrase: “I know what’s coming.”

Sound weaves through these poems: A soprano’s voice is “a wine goblet / filling, then pouring out”; a scarf makes music “settling / across a bared // neck” (the tantalizing delay in those linebreaks!). Sound carries history: In “Family Reunion,” the speaker’s Cleveland cousins’ Southern accents tell the story of the Great Migration, but their children have “inflections flattened / to match the field they thought / they were playing on.”

Dove’s attentiveness to the consequences of both insidious and outright racism begins with the section’s first poem, “Bellringer” a persona poem in the voice of Henry Martin. Born into enslavement at Monticello on the day of Jefferson’s death and for decades the bellringer at the university Jefferson founded (now the University of Virginia), Henry Martin confides, “I listen in on lectures whenever I can, / holding still until I disappear beyond third person.” In this poem Dove makes his life both visible and audible: “I ring in their ears,” he says, “down in that / shining, blistered republic.” Blister: a wound, a chafing that rises, ready to burst.

“Wherever a wall goes up, it smolders,” Dove writes in “Ghettoland: Exeunt.” From Renaissance Venice’s Jewish ghetto (the origin of the term) to the Theresienstadt (Terezín) ghetto and concentration camp, from Jim Crow-era Birmingham to present-day Ferguson, “After Egypt,” Playlist for the Apocalypse’s second section, considers communities that the culture and/or race in power has pushed to the margins. Dove carefully selects personas to convey both the misery and the defiant survival of those tossed onto the “slag heap of your regard.”

In the voice of Sarra Copia Sullam, a central literary figure of the Venetian Jewish ghetto, Dove constructs an elegant riposte to those who would have Sarra abandon her faith in the sonnet “Sarra’s Answer,” then shifts to her tired sadness in “Sarra’s Blues”: “I am not the one you think I am / (my bed is stale the air is sweet).” Three centuries later, another Jewish woman, nameless, wonders, “where did we leave from? / when do we stop leaving?” in “Sketch for Terezín.” These questions are repeated twice, with subtle changes: tense (from present to past, suggesting the finality of exile and imprisonment), disappearing punctuation (a dulling, deadening effect on the voice), and the reversal of “when” and “where,” underscoring how the ghetto functions in both time and space.

Not all walls are literal. In “Aubade West” (the epigraph identifies the setting as Ferguson), the speaker says, “Voice in my ear hissing Go ahead, leave. / No gates, no barbed wire. / As if I could walk on water.” This comes as a potent counterpoint to “Aubade East,” whose optimistic speaker describes the “East River / twerking her bedazzled behind / while the sky spills coins like a luck-crazed / Vegas granny flush at the slots.”

“This morning’s already good,” says the child speaker of “Youth Sunday,” another optimist: “today we are leading in the congregation. / Ain’t that a fine thing! All in white like angels.” The congregation she and “Addie chattering like a magpie” belong to is the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. With this use of persona, Dove brings the tragedy and horror of the 1963 bombing into the present tense, though in the poem’s time it is yet to come.

Less compelling is the single persona extending through “A Standing Witness,” the book’s fourth section, in which Dove provides the libretto for a song cycle about key episodes in the last half-century of American history. Despite memorable poems like “Wretched,” an abecedarian on the AIDS epidemic (“fear fueling rumors as the flowers / Germinate and spread, voracious: a purple hemlock / Inching trunk to collarbone, jaw to ear to eye”), and “World-Wide Welcome,” a whirlwind tour through 90s pop culture, this sequence’s compression prevents the full deployment of Dove’s formidable talents.

In “Spring Cricket” and “Eight Angry Odes” (sections three and five, respectively), those talents find their outlet in sharp-eyed, world-weary speakers frustrated with the world’s failings and life’s troubles, minor and major. After triumphantly claiming the power of the poet’s art in the sonnet “Climacteric” earlier in the book (“I’m not ashamed: // each word caught right is a pawned memory, humbly reclaimed”), Dove’s cricket chirps a plaintive addendum: “Tired of singing for someone else. / Tired of rubbing my thighs / to catch your ear.”

In an endnote to the book’s final section, “Little Book of Woe,” Dove reveals that for the past twenty-some years she has been living with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Though treatments led to improvement in symptoms, she kept the diagnosis private. In these riveting poems, Dove shares her experience with chronic illness, from the litany of medications and treatments, in “Rosary,” that take time that would otherwise be devoted to writing, in “This Is the Poem I Did Not Write,” to the brutality of pain. She catalogs its types (“cold pain, shitty pain / a shock, a shirring, a ripple”) and flavors (“sweet is the worst”), and shows how difficult it is to think around, in “Voiceover.”

At the moment just before the doctor’s verdict, she suddenly wishes for homemade soup, “the real deal,” in “Soup”:

all that saturated glistening scent stoking the house

with memories: the Jewish boy I kissed

until we both sank to our knees in the grass,

my mother’s frown as she plucked weeds

from my hair—oh my mother will die from this,

my mother whose soup is the best

even though it was always oversalted because

it was labored over, it was ladled out

unconditionally, tendered sweetly

without consequences, a nonjudicial love—

An indrawn breath before the dive, this long sentence stretches the length of the page, drawing the past—memory and family so artfully rendered, recalling especially the book’s first section—into the present, toward the future about to be named. Illness too, is “nonjudicial,” not in affection, but in affliction; the mother’s “unconditional” care stands opposed to its inexorable force.

In the poem that is the source of the collection’s title, Shakespeare “pens a sonnet while building / a playlist for the apocalypse.” With this book Dove, too, performs such a feat. It is a privilege to observe such a brilliant mind working through multiple difficult subjects at once, with grace and wit to spare.

Playlist for the Apocalypse, by Rita Dove. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, August 2021. 128 pages. $26.95, hardcover.

Carolyn Oliver is the author of Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble (University of Utah Press, 2022), selected by Matthew Olzmann as winner of the Agha Shahid Ali Prize. Carolyn’s poems appear in The Massachusetts Review, Indiana Review, Cincinnati Review, Radar, Shenandoah, 32 Poems, Southern Indiana Review, Cherry Tree, Plume, DIALOGIST, and elsewhere. Her awards include the E. E. Cummings Prize from the NEPC, the Goldstein Prize from Michigan Quarterly Review, and the Writer’s Block Prize. (carolynoliver.net)

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.